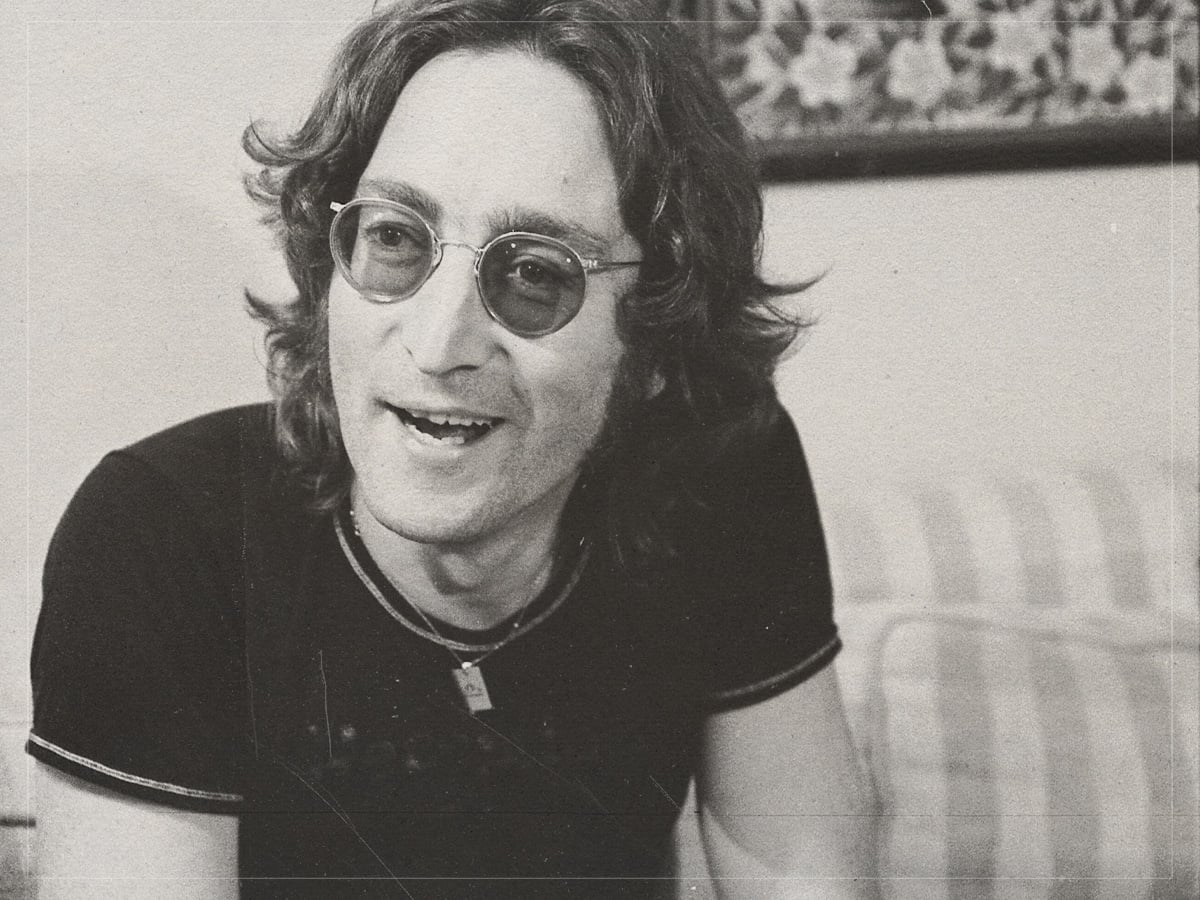

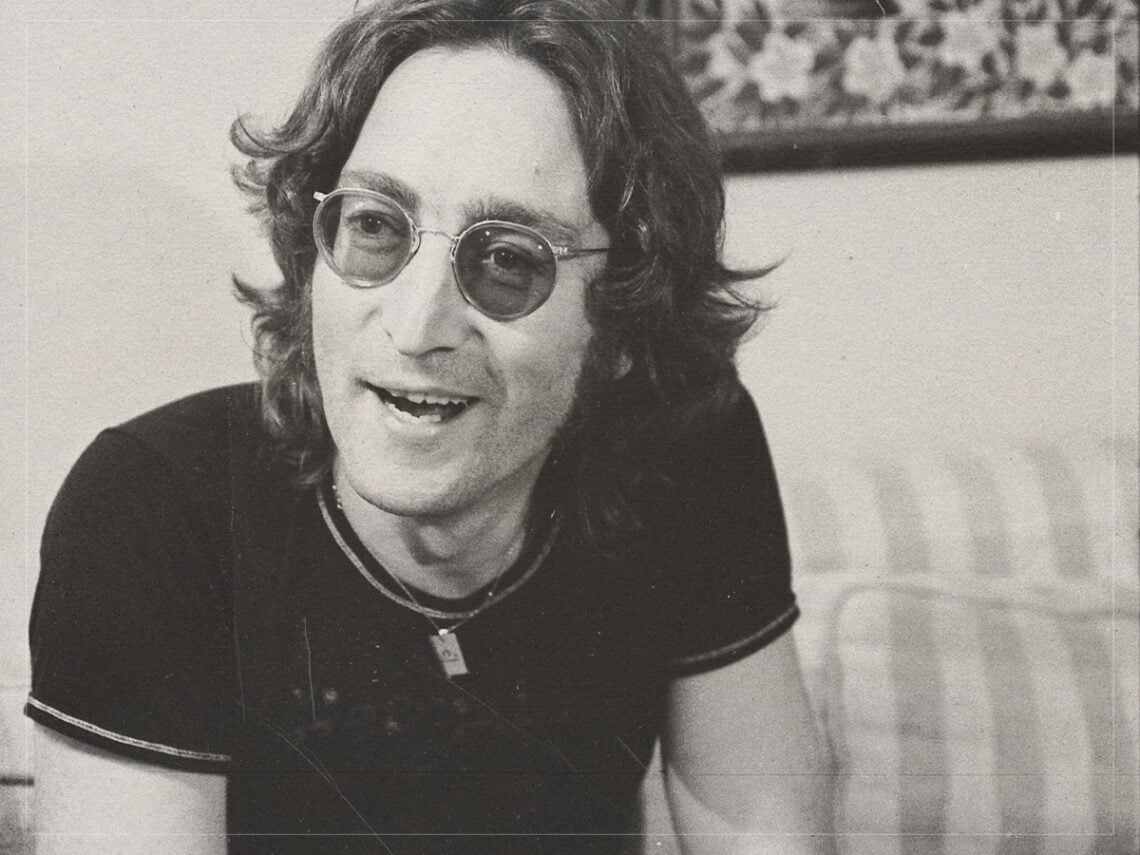

(Credits: Far Out / Tony Barnard / Los Angeles Times / UCLA Library)

Sat 14 February 2026 21:30, UK

The song ‘Bony Moronie’ was a big hit in 1957 for the pioneering New Orleans rocker Larry Williams, so much so that just about any kid who picked up a guitar around that time knew the riff, something John Lennon probably should have realised.

By the time Lennon sat down in the studio to record his own version of it in 1973, however, he wasn’t in the best headspace for critical thinking. This was smack dab in the middle of the infamous ‘Lost Weekend’, an embarrassing two-year period in which Lennon became a less-than-functional alcoholic, palling around with Harry Nilsson and wasting both of their talents on booze and debauchery.

The ‘Bony Moronie’ cover was part of the project that would eventually become the album Rock ‘n’ Roll, a supposed celebration of the songs that had inspired Lennon in his youth and that had remained some of his favourites to play over the years. Unfortunately, he had contracted Phil Spector to produce the record, who was in an even worse state than he was. Along with a similar substance abuse problem, Spector was mentally unstable, firing off a shotgun inside A&M Studios at one point, and on another, absconding with the master tapes of the Rock ‘n’ Roll sessions and disappearing for two months.

Dragged into this circus were the musicians whom Spector had hired to play on the record, including no shortage of esteemed names and session all-stars: Steve Cropper, Jose Feliciano, Leon Russell, Hal Blaine, Jesse Ed Davis, Eddie Moutau, and Jim Keltner, among many others. One session player who was credited as playing on Rock ‘n’ Roll when it was finally released in 1975, however, now says that he doesn’t actually appear on the record.

In an interview last year on YouTube with Thinking About Guitar, the great session guitarist Larry Carlton discussed why he walked away after one frustrating night in the studio with Lennon. “It was a 7 o’clock session,” he recalled, “By 9:30, still no John Lennon and Phil Spector. So [Leon Russell] and I are just sitting around A&M Studios… So, John and Phil finally get there, 10 o’clock or something, and—I didn’t tell this story for a lot of years—but it was a bad time for John. He was drinking.”

Carlton was a fan of the ex-Beatle and had been excited about working with him, but he was also a seasoned pro. During the mid-70s, he recorded with a ridiculous variety of big-name artists, from Steely Dan, Joan Baez, and Joni Mitchell to the Four Tops, Barbra Streisand, and the Partridge Family, and was thus expecting a basic level of respect and professionalism.

“So, we’re gonna do a song, and they call it ‘Bony Moronie’,” he continued, “Well, I played ‘Bony Moronie’ when I was 12 years old. So I’m in my cubby here, and John’s right here, and he’d been drinking, so he’s calling the chord changes [as we play]. There’s only three.”

After listening to Lennon shout the simple chord changes at him during a few run-throughs, Carlton felt demoralised.

“It was a drag,” he said, “It was not professional… So we finished that night’s session, and I drove Leon Russell back to his hotel, and he said, with his Oklahoma accent, ‘I’m back to Tulsa in the morning’. I got home and called Phil Spector’s office and just left a message at midnight and said, ‘Sorry, I can’t make it for the rest of the week’. So I cancelled. It wasn’t how I wanted to spend my time. It could have been so cool, but it was one of those things.”

Sadly, Carlton never got to work with Lennon again, noting candidly, “I’m an admirer, but that wasn’t a good time”.