An invisible class of gatekeepers supports our ability to scroll all day on Instagram or TikTok with limited risk of seeing something explicit, disturbing, gruesome, or illegal: content moderators. They protect us, of course, at the detriment of their own well-being, sorting through mounds of disturbing content deemed too horrible or dangerous to be seen on social media platforms, from shootings and nudity to dismemberments and suicides.

The protagonist of Elaine Castillo’s Moderation is one of these invisible content moderators, and she’s damn good at it.

Girlie Delmundo—a pseudonym—is closed-off and levelheaded, splitting her time between a job that frays her psyche and her obligations to her large Filipino family. She is so consistent in her content moderation role that she’s plucked from her existing role at Reeden, a social media company, to join the team at Playground, a burgeoning virtual reality platform recently purchased by Reeden. Girlie can watch videos of pedophilia and beheadings without flinching, so Playground picks her to don a synthetic suit of sensors and a headset when they begin welcoming visitors to a new terrain, blending social media with the immersive worlds of video games. Her job is to find those who behave badly—stabbing people, assaulting them, forming hate groups, all in virtual reality—and boot them from the platform.

The model of Playground is part play, part recovery: Mental health professionals at the company are trying to develop a model to treat people with PTSD and anxiety with simulated reality. But the majority of Playground’s customers are gamers eager to explore the world in a new way: They can travel from their homes, jump back in time, and don the appearance and lifestyle of a whole new person.

It would be easy to write a hackneyed book about how new technology is scary, how tech billionaires are bad, how profit motive will overtake the greater good, and how we are societally unprepared for the pace of advancement that is being laid out before us. “Virtual reality” and “artificial intelligence” have become marketing buzzwords that prepare readers for these kinds of plots.

Instead, Castillo writes a love story, neither trite nor pandering, over this terrain; it is simultaneously an interrogation of capitalism and tech ecosystems. William, Playground’s founder and Girlie’s new boss, always in a suit, is the reserved parent of an elderly German shepherd. As Girlie ventures into Playground’s virtual reality, she and William orbit each other. Her job as a moderator is to always be observing her surroundings, which include a London pub, a Van Gogh exhibit, and a Roman gallery. But in doing so, she becomes attuned to William in all the virtual worlds they inhabit and begins to fall for him.

Castillo writes about love like someone who has experienced it with every sense in their body. “Girlie hadn’t felt anything resembling true desire in so long, now the old reaper hit her like the first drink after a hundred sober years,” she writes. “So Cupid’s arrow had come for her. Fine. Not just a tangential graze, but: full penetration, no exit wound.” Like a great romance writer, Castillo draws readers to the bend of William’s elbow, the heat that radiates off of him, the thrill of running into him unexpectedly.

In writing about love—and about simulated reality—Castillo leans in to immersion, the sense that all senses are tuned and reactive. Virtual reality popcorn has a crunchy texture and distinct flavor; simulated water floats Girlie’s body and runs over her face; she runs her fingers through the fur of an animal; her body heats up with lust. The book teems with detail that lends credibility to the overall project of simulated reality—none of this is hastily generated AI slop. And if something feels this real, who’s to say it isn’t?

But in this new world of virtual reality, it turns out, humans are still prone to push boundaries and plunder and harm. Content moderators still have a job, but it’s one that puts their bodies on the line as much as their minds. Outside of work, Girlie comes from a family that has seen financial ruin, giving her an unwavering skepticism of big tech’s grab for wealth and the unforgiving quality of capitalism. This tactile world she joins must be hiding something, she knows.

There was a brief moment in the book when I prepared for Castillo to succumb to the temptation of a predictable plot, allowing the hero to be too good and the big corporation to be evil. Instead, she skillfully avoids simplicity, revealing all new depths of her characters and their motivations. There’s something more to see here, Girlie realizes, something more to open up to. The question is whether being more than just a moderator will sweep her into Playground’s world or if she can maintain the reality beneath her feet.•

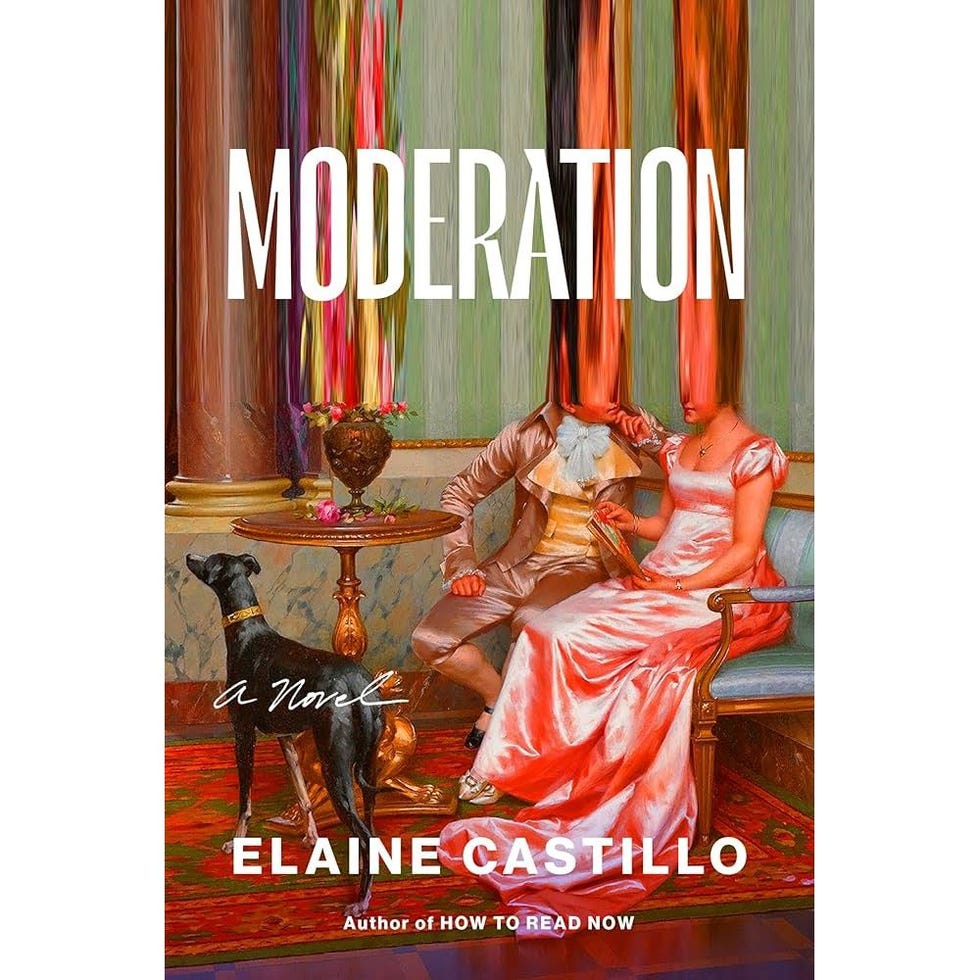

MODERATION, BY ELAINE CASTILLO

Jessica Blough is a freelance writer. A former associate editor at Alta Journal, Blough is a graduate of Tufts University where she was editor in chief of the Tufts Daily.