For generations, the bungalow has stood as a symbol of British aspiration: independence, affordability and comfort under one roof (Image: Getty Images)

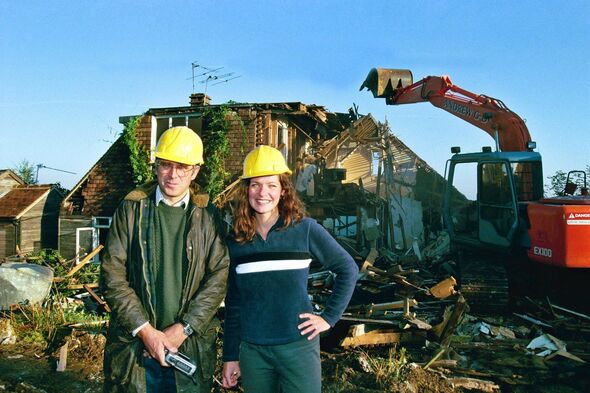

I’ll admit it: I’m a “bungalow gobbler”. Obsessed with the dream of building my own home, in 1997 I set my sights on a half-acre plot in Pulborough, West Sussex. The problem was that the rural spot already had a building on it.

In my hunt for land, it had soon emerged that the only way to secure a half-decent and affordable plot in the countryside was to

gobble up a tired, post-war bungalow.

Unloved and low-slung, it was the perfect candidate for demolition – making way for my kit house imported all the way from Boston, in America. The upside – as the Grand Designs effect had not yet taken hold of a nation of self-builders-in-waiting – was that the shabby bungalow cost me just £100,000 to buy, plus a few thousand more for the demolition of the existing structure.

In 2000, I achieved my dream – documented through a dozen articles in the Daily Express property section and in the second series of Channel 4’s Grand Designs – and soon, that little bungalow was a distant memory, replaced by a triple-storey house that hauled my sleepy lane into the 21st century with cedar cladding and an assertive use of double-height glazing.

Back then, and still so today, snapping up a bungalow is often just shorthand for buying land.

Take Sandbanks in Dorset – the country’s most expensive coastal enclave, where homes now average a jaw-dropping £1.28million.

Here, modest post-war bungalows are routinely razed within weeks of purchase. Few remain. Buyers see them not as homes but as “site value” – the cost of land minus demolition fees – with replacement houses selling for millions.

Yet, as I bulldozed that modest semi-derelict property to make way for something much taller, I unwittingly became part of a nationwide trend that has pushed bungalows to the brink of extinction.

Only around two million true bungalows remain in England and the number is falling every year due to redevelopment.

While demand remains high, particularly among downsizers, they account for just over 1% of new-build completions. This is a significant drop from 6.9% in 2000, which, even then, was viewed as a looming crisis in accessible housing.

The UK is now facing a significant shortage of bungalows, with new-build single-storey homes now on the “critically endangered list”, according to the National House Building Council. Today, less than one in 50 new homes is a bungalow because developers make more money from houses and flats on the same footprint.

This means that with our ageing population, demand will soon far outstrip supply unless policies change. “It’s the bungalows that get snapped up, at high prices,” says a resident of the sought-after retirement town of Sudbury, Suffolk, about the allure of the one-storey lifestyle.

By 1951, there were more than 156,000 new bungalows built in England and Wales.

Recent figures reveal that the number of bungalows under construction has reached an 80-year low. In the third quarter of 2023, only 228 bungalows were registered to be built in the UK.

In fact, the UK needs to build twice as many bungalows as it is currently doing to meet the demand from retirees, according to one survey this year. Five million older people would like to move to a retirement bungalow, primarily because of them being single-storey, according to a poll of 1,000 65-and-overs for retirement developer McCarthy Stone.

Julie Alexander’s bungalow in Peacehaven, East Sussex, was built 25 years ago in the garden of an original property (Image: Adam Gerrard )

And as the shortage intensifies, potential purchasers are going to great lengths to secure their dream home. After a three-year search and 22 handwritten notes through letterboxes, in 2024 Jo and Andy Pennell managed to secure a new three-bed

bungalow near Cirencester, built by Newland Homes.

“Our previous home was maintenance-hungry, with a big garden,” says Andy. “It also took a fair bit of heating. Now, we don’t have to worry.”

A surge in demand for bungalows has seized the current housing market, driven by a growing number of downsizers, retirees and those with mobility needs. But very few housebuilders have stepped up to meet this challenge, preferring to prioritise houses due to greater land efficiency.

Bungalows continue to offer unique benefits, being ideal for people with mobility challenges or those wishing to future-proof their living arrangements with a single-storey freehold property rather than a flat with all the associated – and frequently unpredictable – service charges.

Retired couple Julie and Ian Alexander bought their dream forever home – a spacious bungalow in Peacehaven, Sussex – four years ago.

“We have three dogs so we needed a garden; a flat didn’t appeal,” says Julie, 66, a former nurse, for whom the single-storey layout was essential due to health concerns that make stairs unmanageable.

Their bungalow, built 25 years ago in the garden of an original property on the site, represents precisely the kind of accessible housing that is increasingly hard to find.

“Ideally, as a nation, we would be building more bungalows for older people to enable them to stay in the area,” Ian, 68, explains. “But everything is being built to a certain density because there’s government pressure on councils to build a set number of new homes. That’s why developers often opt for houses or flats instead – bungalows just aren’t flavour of the month anymore.”

Ian, a former firefighter now involved with his local council, confirms the widespread frustration: “Lots of local authorities have passed plans for building them, but developers don’t build bungalows – they can make more from houses. They don’t want to flood the market and bring prices down.”

He says the logic is simple: “If you can build a block of eight flats, that’s eight times more housing than a single dwelling, and more profit for the developer.”

The couple’s four-bedroom bungalow, which cost £450,000 and is now worth around £600,000 due to soaring demand, is just seven miles’ drive out of Brighton – a location they chose to remain close to their adult children.

Bungalows are still desired by downsizers, retirees and those with mobility needs (Image: Stuart Harrison/NEWLAND HOMES)

The town itself was established after the First World War as a haven for returning service personnel. Plots were sold for just £10 each, creating one of Britain’s first truly mixed communities. “There are lots of bungalows here and it is a really lovely community,” Julie says. “We wanted to make the move when we were fit enough to purge two decades of belongings.

“I’ve got arthritis and fibromyalgia and I’ve had a knee replacement so we have already future-proofed should I one day need a wheelchair.”

Their story echoes that of thousands across Britain who see bungalows not as a luxury, but as the only practical route to independent living in later life. And according to Age UK, demand for accessible homes is set to soar as Britain’s population ages.

Contrary to popular belief, the bungalow is not an indigenous British housing type but a colonial import from India. The word “bungalow” comes from the Hindi word “bangla” meaning “of Bengal” and described simple, single-storey homes with wide verandas built for British administrators during the Raj in India.

Cool in the subcontinental heat and easy to maintain, these qualities instantly appealed to Brits and by the 19th century, bungalows began cropping up in English seaside resorts. The promise of affordable comfort, privacy and fresh air made them the darling of Edwardian middle-class families seeking respite from crowded city terraces.

It was between the wars that they truly exploded in popularity. During the 1920s and 1930s, mass suburbanisation swept Britain, fuelled by expanding railways and rising home ownership as developers churned out thousands of bungalows across new suburbs and coastal towns.

Today, Newland Homes is one of the few housebuilders taking proactive steps to include bungalows in its mix of new homes.

“Bungalows are a key part of our housing mix because we understand how crucial they are for easy, adaptable and lock-up-and-leave living,” says Marcus Evans, sales and marketing director for the company.

“As people look for flexible, future-proofed homes, bungalows offer a solution to an underserved part of the market.”

So, now it seems like Britain’s love affair with bungalows is on life support, will we really run out of them?

The signs are worrying, yet all is not lost – there may yet be a future for well-designed single-storey homes to help solve both accessibility needs and family housing shortages – if only planners start to recognise their value.

Looking back at my own experience as a “bungalow gobbler” in Pulborough nearly three decades ago – albeit the fact I was knocking down a semi-derelict dwelling – I can see what we risk losing each time another single-storey home is razed without thought.

For generations, the bungalow has stood as a symbol of British aspiration: independence, affordability and comfort under one roof. If we want future generations to enjoy that same freedom – especially those who need it most – it’s time we stood up for our endangered one-storey wonders before it really is too late.

Self-confessed ‘bungalow gobbler’ Jane Warren who purchased a bungalow purely to demolish it (Image: DX)