Book Review

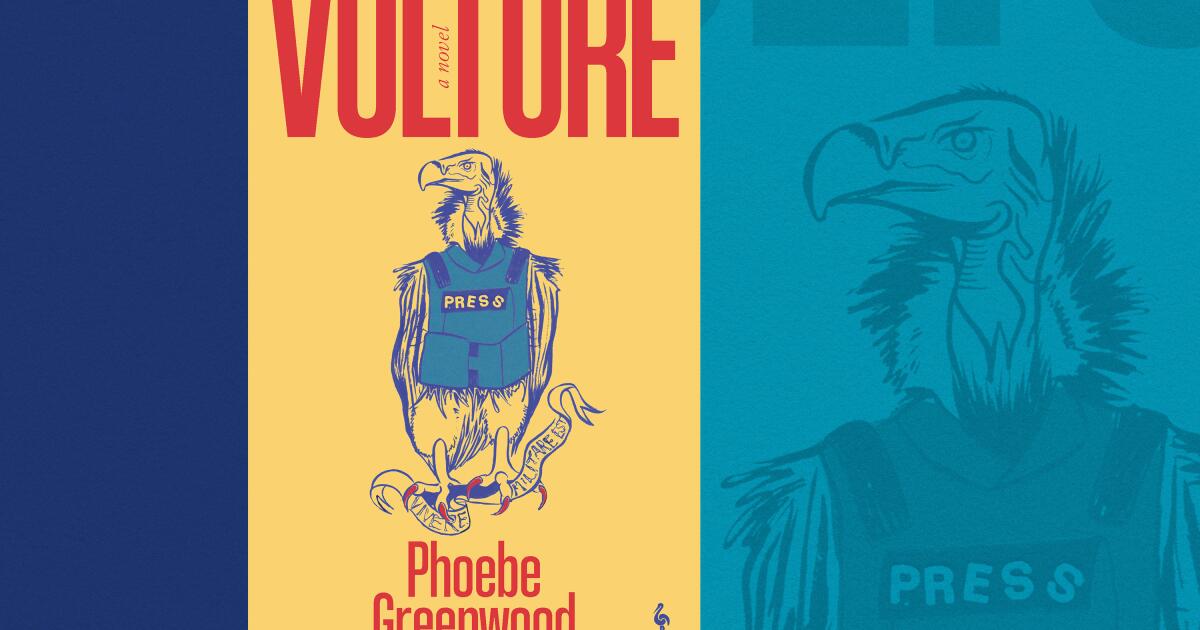

Vulture

By Phoebe Greenwood

Europa Editions: 256 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“Doctor Strangelove,” “Catch-22,” and “M*A*S*H” collide in British journalist Phoebe Greenwood’s blistering debut novel, “Vulture,” a darkly comic, searing satire grounded in historic politics, suffused with incipient journalism and imbued with self-aggrandizement.

Dominoes fall quickly and hard for 33-year-old budding reporter Sara Byrne, assigned as a freelance stringer by the fictional London Tribune to cover the 2012 Gaza War. She is ambitious and clueless. A nepo baby, she’s certain a scoop will make her career and bring her out of the shadow of her recently deceased father, Bill, a foreign affairs writer considered a titan among the giants of Fleet Street. She finds herself ensconced in all-expenses-paid headquarters for foreign correspondents like her: the Beach, Gaza’s four-star “nice hotel,” an “oasis of humanity in a blighted desert” featuring a room with uninterrupted sea views and shrimps in a clay pot. Observing the consequences of conflict, Sara soon realizes she is embedded in her own emotional war zone.

The Beach is a convenient location for mingling, networking and seeking contacts through a fixer, someone essential for foreign correspondents. Sara’s fixer is Nasser. He introduces her to an aged, grieving Palestinian widower who has lost his whole family in a bombing, but she doesn’t see any point in even being in Gaza if the only story “was sad Mohammeds talking about their dead kids and dead wives and neighbors and so forth.”

She dismisses ongoing attacks, thinking everything is “getting a bit samey.” A morgue visit elicits disinterest and little more than a body count, with Sara wondering if “ten makes a massacre. I only counted six.” In a crowd of dead, limp bodies, she spots a sobbing Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist and exclaims, “What good is a crying photographer to anyone?” Heartless, she wants a bigger story, something that would put her byline on the front page. If Nasser can’t get her into Hamas’ underground tunnels “where all the men running the war were hiding with their rockets,” then she would have to find someone who could.

That someone appears to be Fadi, part of the fixer culture. He wore “skin-tight black jeans and a black t-shirt with I Heart Brooklyn written on it in red, loopy letters” and “stank of aftershave that could easily have been his sister’s perfume and smoked cigarettes greedily.” His alluring credentials include an uncle he claims is a top fighter in the resistance who can get Sara a meet and greet with the leader of the Al-Yasser Front. Fadi promises a photo shoot with black balaclavas, guns and black flags. Foolhardily, defying Nasser’s caution, Sara offers Fadi $1,000 for an excursion into the “terror tunnels,” certain this will give her a proper story to write rather than what she terms “monkey journalism.” Instead, after several delays and setbacks, she finds herself involved in an excruciatingly senseless death when the Beach’s restaurant is bombed.

London-based Phoebe Greenwood was a freelance correspondent in Jerusalem before working for the Guardian as an editor and correspondent.

(Sandra Semburg)

Greenwood’s graphic details are vivid and disturbing, from screaming that is “a high unnatural wail that could shrivel souls like salted slugs” to air “powdered with concrete and sulfur.” With dead bodies scattered around her, Sara, her hands dripping a trail of blood, retreats to her room, feeling responsible for one particularly shocking death.

A series of flashbacks sprinkled throughout the novel highlight the deep psychological wounds Sara brings to her wartime experience. They underscore the guilt she carries from traumatic relationships with her father, mother and an adulterous affair. She believes she can never match her father’s success as a reporter and on the first anniversary of his death, instead of visiting his grave, her mother takes her to a Sloane Square department store (because that’s where she was taken as a child to buy shoes). Her clandestine involvement with her father’s close friend and literary agent, whose wife is dying of cancer, implodes, leaving her a bitter “other woman” living her own soap opera. It complicates a sexual encounter with an Italian cohort in Gaza.

One of those flashback chapters, “The Cradle of Civilization,” unravels the ironic, ravaging narcissistic, perhaps psychopathic implications of the title. Like the bird of prey seeking carrion, a foreign correspondent is characterized as a misery merchant or conflict cowboy, making a living from death and disaster. Even as their function is to give voice to the voiceless, Greenwood writes, their assignment is to “stand in the middle of something,” to understand (from the Old English, understanden) and listen. As they do so, like Sara, seeking a “defining moment” they might morph into news cannibals.

And then there are the other birds. They are scattered throughout the novel. Keep an eye on them. Sara does. The literal ones and the magical, metaphorical ones. The first sighting is a simple one, easily dismissed. A manky bird on her balcony jolts Sara from semi-wakefulness right after she’s had a dream of her dying father. Its habitual appearance becomes disconcerting. Is it just a bird or is it a harbinger of doom and death? She begins to think of it as a “deranged stalker,” a “horrifying, tapping shitting bird,” terrorizing her. Eventually, Sara, her health deteriorating from what appears as an undiagnosed illness, begins to hallucinate, seeing the bird’s “heart beating visibly under its feathered ribs, its metallic purple face,” culminating in believing the bird has transmogrified into a talking pigeon that is her father.

Greenwood’s stinging, salient novel remains relevant (the more things change, the more they stay the same), excoriating those who make a business of war whether it’s public or personal. As the owner of the Beach observes: “War may be hell but it’s one hell of an employer.” “Vulture” is a provocative, uncompromising powerhouse of a read.

Papinchak, a former university English professor, is an award-winning book critic in the Los Angeles area.