Review:

“Abraham’s Boys” comes with the subtitle “A Dracula Story,” which I guess it technically is as long as you have a liberal interpretation of what “Dracula” entails in this context. Just don’t expect to see The Count in all his cape-and-fang glory. “Abraham’s Boys” ostensibly operates as a loose sequel to “Dracula,” though this movie’s main vampire is a seldom-seen “Pale Man” who probably shouldn’t be taken as the literal Dracula. “Dracula” seems included mainly to bring more attention to the title than the nondescriptive “Abraham’s Boys” is capable of attracting alone.

18 years ago, Count Dracula infamously took a stake to his torso. It’s now 1915. Facing fears of further vampire attacks as well as increasing public scrutiny, Dracula’s destroyer Abraham Van Helsing fled Europe with his wife Mina, whom he somehow scooped up in the wake of her first husband Jonathan Harker’s death, along with their two sons, Max and Rudy.

Likely dictated by what the film’s lean budget found affordable, the Van Helsings moved to Central California, of all possible places. Specifically, they now live in the same white-painted farmhouse with sun-bleached surroundings that every film family settles in when searching for a remote location to call home. Great choice for hiding in relative isolation. Bad choice for a routine backdrop whose blandness holds no eye-catching appeal.

It’s tough to tell if “Abraham’s Boys” should be seen as a sequel to Bram Stoker’s original novel, the Bela Lugosi classic, or some other version of the timeless tale. Whether you go by the descriptions in the book or their depictions in the 1931 film, Abraham and Mina have a four or five-decade gap between their birth years. Maybe that explains why the first time they share the screen here, Mina matter-of-factly acknowledges her husband with, “Abraham, welcome home.” Similarly stiff, Van Helsing responds, “Hello, Mina,” just how any loving couple normally greets each other by first name when coming home from work.

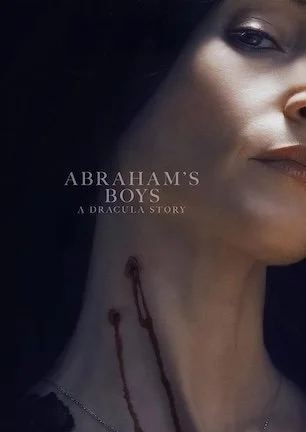

As Mina, Jocelin Donahue curiously chooses to play the part like she’s in a 1930s stage play, either overemphasizing monotone lines or alternately anxious to put the back of her hand to her forehead before fainting. Making odd acting choices of his own, perhaps due to a dour script applying a heavy hand to a theme of overbearing parenting, Titus Welliver portrays his unlikable Van Helsing as an abusive prick, with nary a hint of the quirky charm Edward Van Sloan infused in the same role. Bizarre interpretations of these two characters aren’t easy to reconcile with how they’ve been shaped in the minds of moviegoers after 100+ years of Dracula stories, which is part of the problem posed to an audience attempting to engage with their poorly presented personalities.

Meanwhile, the two boys have their own singular traits to home in one. One brother persistently broods. The other repeatedly blubbers.

“Abraham’s Boys” follows formula to such a tight T, there’s no room to break out of its basicness. With so little action to speak of, the film resorts to typical tricks like starting on a pre-title stinger before settling in for exposition. Multiple fades to black mirror heavying eyelids as sluggish pacing trudges on toward a nightmare sequence, slipped in precisely at the 30-minute mark to wake weary viewers with an artificial jolt. Moderately more activity takes place during the next half hour, except even that is so little that the movie feels the need to add another nightmare sequence along with an ominous zoom into a simple cemetery cross accompanied by manic music better fit for a far more frantic moment.

The suggestion that zoom puts forth has no payout, by the way. However, repeated shots of elder son Max chopping wood to establish what can be called “Chekhov’s ax” pay off exactly how anyone familiar with the concept can predict.

Contemplative musings about inheriting unfortunate legacies and being shackled to burdens from the past are drowned out by a cacophony of commonplace beats, secondary characters almost entirely without purpose, visually uncompelling imagery, and period-specific plodding about tinctures, railroad extension discussions, and other asides that don’t serve the fiction. I’m mildly interested in reading the Joe Hill short story upon which this movie is based, largely because it’s difficult to imagine an author of his talent churning out something so narratively unfulfilling. The cat in this case killed my curiosity to investigate where potential disconnects lie though, as “Abraham’s Boys: A Dracula Story” tastes so plain, I’m not compelled to revisit it, even in another format.

Review Score: 35