Before the Tour de France even ended, online cycling publication Domestique asked in a headline, Is Pogacar bored by his own dominance?

Soon after the Tour ended, Velo offered answers to the question with an article describing Why Pogačar Was Bored at the Tour.

A search for “bored Pogaçar” yields dozens more results. It’s a topic that cycling journalists have decided is worth writing about — presumably because we readers find it worth reading about.

Speaking with my fellow tifosi, I hear not just interest, but indignation. How dare the Tour winner exhibit ennui?

Why such frustration from us fans? After all, some of the highest praise we typically grant our athletes is that they “make it look easy” — and when you find a pursuit especially easy, you’re likely bored by it.

(Mind you, I haven’t actually seen evidence that Pogaçar has entered full eye-roll mode; while he didn’t exhibit the same joie de vivre that we’d seen in past Tours — no full-kit pool antics on Rest Day — he never grumbled in a press conference or avoided fans. But maybe that reinforces the point: even a hint of insouciance is annoying to us fans.)

My hypothesis: Because cycling fans are disproportionately cyclists themselves, we want to believe that we’re not so different from our heroes, and that we feel what they feel. And what we feel when we ride bicycles — and especially when we race them — is suffering.

Fans of other sports remark at their idols’ grace, their artistry, their efficiency, or their might; we can imagine that these qualities are what the athletes enjoy exhibiting as well: How must it feel to soar gracefully (and powerfully) like Anthony Edwards or to swim with the sleek efficiency of Michael Phelps? We can quite literally only imagine.

The most beautiful piece of sportswriting I’ve ever encountered is David Foster Wallace’s description of Roger Federer playing tennis. It’s thousands of words long, but can be summarized as: No one else will ever play tennis like this; it’s stunning to watch; and no one but Federer can know how it feels to play tennis like this.

But if elegance, harmony or raw, explosive power are honored in other sports, it’s suffering and joy that we cyclists hold dear — because we can know how these feel. What weekend group-ride warrior hasn’t felt their lungs heave, their quads sear as they close in on a wheel or drag themselves up a local climb and thought, “This is cycling; I’m suffering, just like a pro.”

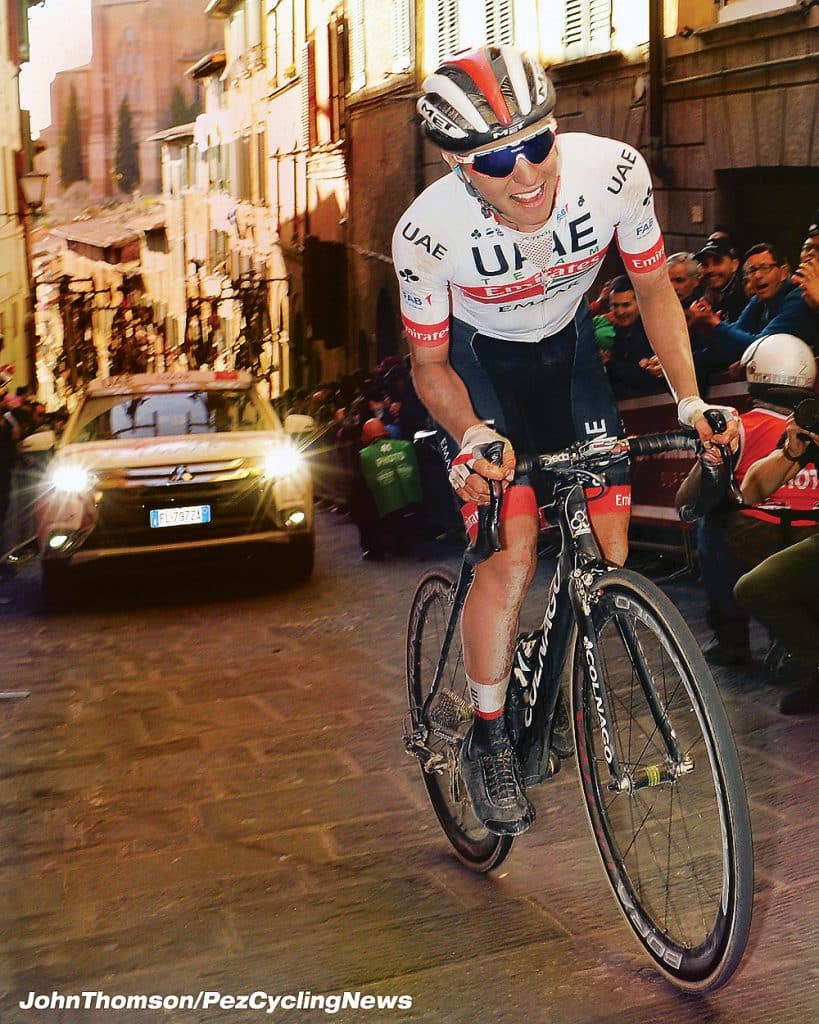

We pay homage to the riders who clearly do suffer: the Enric Mases, the Sarah Gigantes, the Romain Bardets, the — I’ll dare write it — Jonas Vingegaards. An entire book is devoted to The Art of Suffering; I’ve just pored over its photos, fascinated, because I believe that at some point, somewhere on an ascent of Mt. Diablo or in the closing meters of the Tuesday Night Hammerfest, I’ve suffered, just as these pictured riders so evidently have suffered.

Not to suffer, then — to make it look easy — is a violation of a cycling norm. Cycling fans get very close to their champions, both literally and emotionally: We can touch them when they ride by, and we believe that we can feel what they feel.

So when Pogaçar appears bored, even telling us he may be done with cycling within the next few years, he distances himself from those of us who would otherwise be his most devoted followers, we who watch bike races, and who ride bikes, and who for occasional moments believe we share his experience.

Please don’t misunderstand: I don’t even know what it’s like to win a master’s criterium, so I certainly can’t relate to winning the Tour de France. But I can believe that I suffer when I chase a KOM, or a buddy’s attack, and I can believe that my suffering is something like the G.O.A.T.’s.

I just can’t believe it’s that easy for him.