Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Vanished parents are a staple of children’s literature, with authority figures banished so that the young protagonists can find adventure and discover their own path. When the trope appears in adult literary fiction, the effect is far more troubled. Adult characters feel the loss of parents as a hurt that never quite heals.

In House of Monstrous Women by Daphne Fama (Bantam £16.99) Josephine and Alejandro del Rosario lost their parents in the cruellest fashion — assassinated by political allies of President Marcos of the Philippines. Alejandro moves to Manila with his sweetheart Gabriella to take up the fight against oppression, while Josephine remains behind in the gloomy Rosario house in provincial Carigara, fondly remembering how they used to play hide-and-seek with their childhood friend, Hiraya Ranoco. When Hiraya extends an invitation to the Ranoco mansion to play again for old times’ sake, the trio agree with varying degrees of trepidation; Ranoco women can seemingly commune with spirits. Arriving at the remote island base, they discover that this version of the game involves staying hidden until dawn lest their lives be forfeit.

Some novels give the impression of being written with a film version in mind; in Fama’s case it’s a computer game, with the vast, cliff-top-set Ranoco house limited by its developer’s imagination, rather than the structural requirements of an actual building. Staircases tower vertiginously, enfilades of rooms extend to the vanishing point, and every level brings its monster to be faced. The blackened, oozing mansion is a fit metaphor for a country melting in corruption.

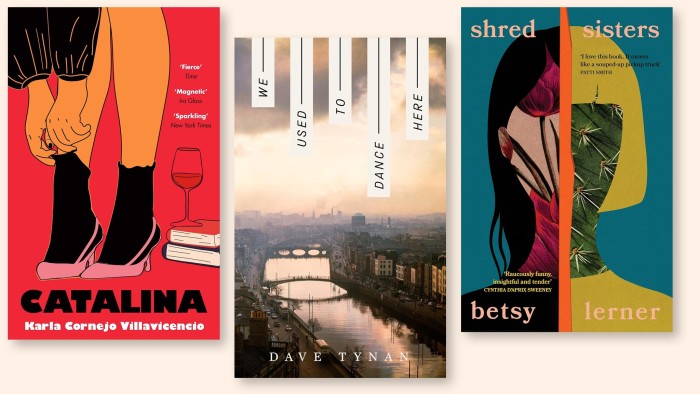

The eponymous protagonist of Karla Cornejo Villavicencio’s novel Catalina (Hutchinson Heinemann £14.99) lost both parents in a car accident and moved from an Ecuador she barely remembers to the US to live with her eccentric grandparents in New York. It’s only much later, when she has a place at Harvard that her grandfather reveals that she entered the country illegally as a child. Catalina is thus a “dreamer”, pinning her hopes on the passing of Barack Obama’s Dream Act that offered a pathway to citizenship for undocumented migrants. The disconnect between her alien status and that of the wealthy, complacent students around her couldn’t be more stark. Yet Catalina is fizzing with wit and sardonic observation, as its heroine tries to align the American literature she loves with the scant opportunities she’s offered.

Amy and Ollie are the warring sibling in literary agent Betsy Lerner’s accomplished first novel Shred Sisters (Verve Books £10.99). Here the parents’ absence manifests as a blind preference for the older sister over the younger. That Ollie lies, thieves and cheats her way through life, only seems to make her more alluring. Ollie is impossible; but also impossible not to forgive, as it becomes clear that mental illness underlies her wild impulses. Demure Amy learns that no one has her back like her infuriating but loveable big sister. A poignantly engrossing tale for anyone caught in the webs of sibling rivalry.

I Want Everything by Dominic Amerena (Scribner £14.99) examines what happens when the familial vacuum is filled by something disturbing. An unnamed young writer glimpses an elderly woman at a Melbourne swimming pool and is sure it’s his literary idol, novelist Brenda Shales, who wrote two shocking experimental feminist novels in the 1970s then disappeared. Living with a more successful writer girlfriend, he sees his chance to make a mark on the literary scene. If he can persuade the reclusive Shales to talk, it could be a bestseller. Brenda languishes in a care home, and a mistake by a nurse sees her accepting him as her long-lost grandson. By not immediately correcting the lie, he soon becomes trapped by it.

From a fairly unoriginal premise — writer pretends to befriend his subject in order to get copy — Amerena weaves a compelling tale around literary composition itself. The narrator and his friends consider that they work on “stolen lands” but who owns and gets to tell a story is much fuzzier. How far a writer even resembles their work is one theme, believable cross-gender narration another. Brenda seemingly excels at portraying men in her fiction, while the narrator can’t “do” women. That Amerena himself presents Brenda so convincingly adds another layer of delicious complexity.

Dave Tynan moves convincingly between male and female viewpoints in his short-story collection We Used to Dance Here (Granta £12.99). Dublin is the downbeat setting, a zone of inertia whose inhabitants are forever trying and failing to make authentic connections. For the jaded young woman in “The Sluagh” the city is “pockmarked with her own life”. In “How Do You Know Them”, two people meet at a wedding and might be soulmates, except they never meet again. The general gloom is lifted by Tynan’s fine eye for the telling detail, his terse and exact dialogue and exquisite descriptions, especially of rain. It is Ireland after all.

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X