A few years ago, a charity that supports retired journalists visited the FT’s London office to gather contributions. These would help support an old folks’ home in the country.

At first, the mood in the presentation room was gloomy. Then the visitors screened some slides of the rural retreat. One snap showed a well-stocked bar where a scrum of merry old scriveners were raising their glasses. Evidently, they were still able to exercise three core journalistic competences — drinking, gossiping and causing gentle mischief.

Spirits in the room were lifted too. I could see my thirsty colleagues thinking: “It does not look half so bad as I thought.”

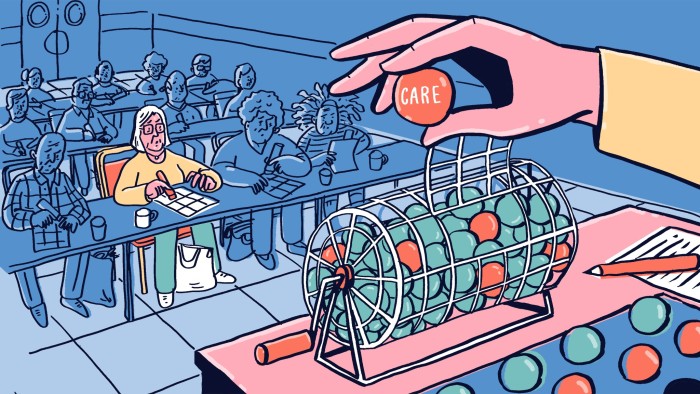

The latter observation also applies to the financial risks that possible care home stays create for retirees. These matter if you plan to retire in the next few years, have already done so or have an elderly relative.

Most older people remain in their own dwellings as long as possible. “People have a lot of pride in their homes. There can be a loss of identity if they have to move out,” says Mel Kenny, a chartered financial planner at Radcliffe & Newlands Wealth.

Younger relatives who mention care homes to an elderly relative may suffer the riposte: “They kill people in those places, you know!” An anecdote may follow concerning an acquaintance who survived the Blitz. The punchline will be that Sunny Uplands Senior Living succeeded where the Luftwaffe failed.

You can leave care home brochures for an elderly relative to “take a look at” as I have done. Months or years later you are quite likely to find yourself binning this bumf while clearing the dwelling where the dear departed held out with the gallant tenacity of the Spartans at the Battle of Thermopylae.

I have no personal kick against care homes, apart from their variability. The worst are threadbare places smelling of catering gravy, disinfectant and despair. The best — including the nursing home where my mother stayed — are clean, caring and cosy.

And so to Q&A.

How likely is a care home stay for the typical person?

Census data shows that around 3.2 per cent of UK women and 1.6 per cent of men over the age of 65 live in care homes.

Us feeble males generally have shorter lives. Female partners often care for us at home on our way out. For both reasons, women account for about 70 per cent of care home occupants.

How long might a stay be?

The common perception of lengthy stays reflects mean averages. These are dragged up by relatively small cohorts of long-lived seniors. A 2011 study funded by care home operator Bupa estimated the mean adjusted stay at two and a half years.

To me, a better proxy for 50/50 probability is the median average — representing the person in the middle of a distribution. The Bupa study estimated this at just over a year and a half.

A woman’s higher survival expectations means her typical stay will be several months longer than this. Male stays are correspondingly shorter.

How much does a care home stay cost?

Nursing care homes for seniors in poor health cost more than residential homes for the relatively healthy. Fees for both are high in London, dropping steeply further north. At a national level, the mid-range weekly charge for a residential home is about £1,200, according to healthcare consultancy LaingBuisson. The corresponding figure for a nursing home would be about £1,500.

I estimate that a stay of typical length in a mid-range UK residential home would cost a man roughly £70,000, or about £90,000 if he opted for nursing care. The ballpark figures for a woman would be £110,00 and £140,000.

These are big costs compared with average retirement savings. “We can expect them to continue rising at a rate higher than general inflation,” adds William Laing, executive chair of LaingBuisson.

But the risk of better-off male retirees incurring unaffordable care home costs seems quite low to me. It is rather higher for women from the same demographic.

In both cases, domiciliary care delivered in the senior’s home by an agency will often be a cheaper, less disruptive alternative. The growing popularity of this option discourages me from predicting a big expansion of the care home population as some other pundits have done.

If I need to go into a care home, how do I pay for it?

Most sole owner-occupiers cannot expect the state to pay their fees. They may receive some small subsidies without any means testing. And they can still count on any recurring pension income to cover some charges.

In England, care home residents with £14,250 in assets contribute to the cost on a sliding scale up to £23,250 in assets.

Above that, they pay the full whack themselves — with choice widening beyond homes approved by the local authority. Your previous dwelling is included in the tally of assets if you were sole owner-occupier. If a spouse still lives there, it is not.

A small minority of elderly people face selling their properties to finance an extended care home stay. This is unpopular, but the government is unlikely to intervene.

If I ever have to sell a dwelling I no longer occupy to pay for my current accommodation, I will try to be philosophical about it. The worry for some people in this situation is that they will spend all their house proceeds on a long stay in a better care home. Having got comfortable there, they might then have to retrench to cheaper accommodation paid for by the local authority.

It is possible to cap liabilities with an immediate needs annuity. These products cover costs as long as you live. But they are expensive — one online calculator puts the cost at over £150,000 for an 85-year-old with pensions income of £32,000 a year and annual fees of £62,000 to cover. The Society of Later Life Advisers is a good starting point for advice here.

Finally, if the prospect of entering a care home scares you, remember that the low likelihood of this is not the only comfort factor. Love, humour and comradeship can make any move more bearable.

During the brief care home stay of my wonderful mother, a former teacher, a doctor tested her cognition with a pop quiz. First, he asked her if she remembered who he was. “No,” she said. Then he asked her what year it was. She could not recall.

His final left-field question concerned the unpopular education minister of the day.

“Do you know who Michael Gove is?” he asked.

“Yes,” she replied, quick as a flash, “he’s an idiot.”

I regret to inform any fans of the Tory politician that everyone in the room burst out laughing.

Jonathan Guthrie is a writer, an adviser and a former head of Lex; jonathanbuchananguthrie@gmail.com