Ray Brown: His Life and Music; Lee Berk: Leading the Berklee Way; Mbaqanga Nights

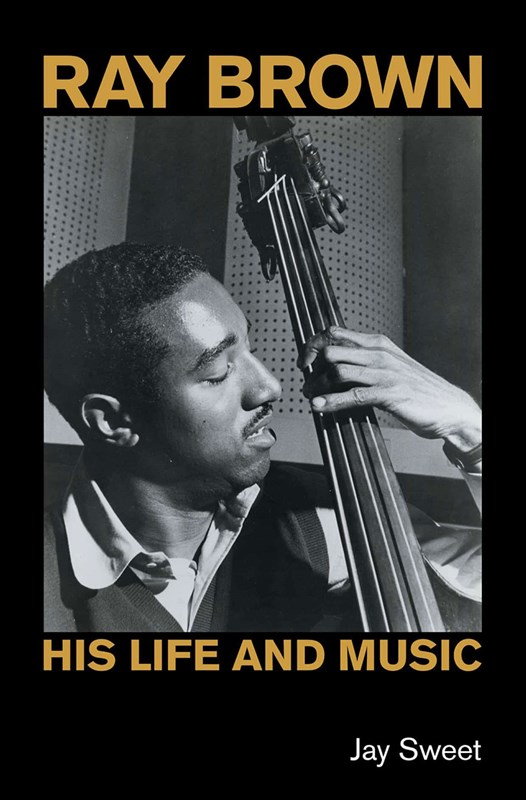

Ray Brown: His Life and Music

Jay Sweet (Equinox HB £32.50)

Though his physical stature didn’t match Ron Carter or Leroy Vinnegar’s, Brown was a giant of the double bass and, to this day, his playing is an ideal to aim for when playing straightahead jazz.

An early fan of Jimmie Blanton and his successor Oscar Pettiford, Ray was sufficiently talented to be working with the Gillespie-Parker quintet in 1945 at the age of 19 and, after Gillespie’s big band, migrating to Ella Fitzgerald’s trio and Jazz At The Phil from 1947.

From there on, his work can be divided into two periods, one with the Oscar Peterson trio and the JATP crew from 1950-65; followed by the busy existence of a versatile studio musician and occasionally bandleader, producer or personal manager.

One can imagine a potential biographer’s problem of how to cover such a well-ordered life. Brown was 21 when he married Ella Fitzgerald (almost a decade older than him) and, after they adopted a son and then divorced; Ray married Cecilia for nearly 50 years, but there’s little space devoted to his personal existence. Sweet appears to have done several interviews soon after Brown’s death, with his then-recent and therefore younger colleagues, but apart from quotes by Peterson, the comments on the bassist’s earlier work are mainly drawn from contemporary reviews, and the author’s own judgements.

If there’s not much ‘life’ alongside the music here, the writing itself is also somewhat lifeless. When it comes to the studio-bound second half of Ray’s vast output, so many things are briefly mentioned that the reader suffers what I can only call verbal discogrrhea.

Page after page is filled with formulaic descriptions of often obscure albums: Date of next known session, album name and catalogue number, some tune titles with brief comments, and final assessment.

If the lead artist is deemed unknown to the reading audience, you get a single sentence pigeonholing them before assessing Brown’s contribution to that particular session.

This raises the question of whether the book is intended for obsessive record collectors or for double bass students. Some inconsistencies in Sweet’s approach mean that the word rubato is defined but fermata is not, while the phrase col legno gets an explanation but not “fall-off”. There is valuable information contained here, but it’s perhaps easier to dip into than read consecutively. At least, the now increasingly familiar idea of having a closing rollcall of musicians (from Stanley Clarke to Rufus Reid) give their appraisal of the hero provides some focussed relief. Brian Priestley

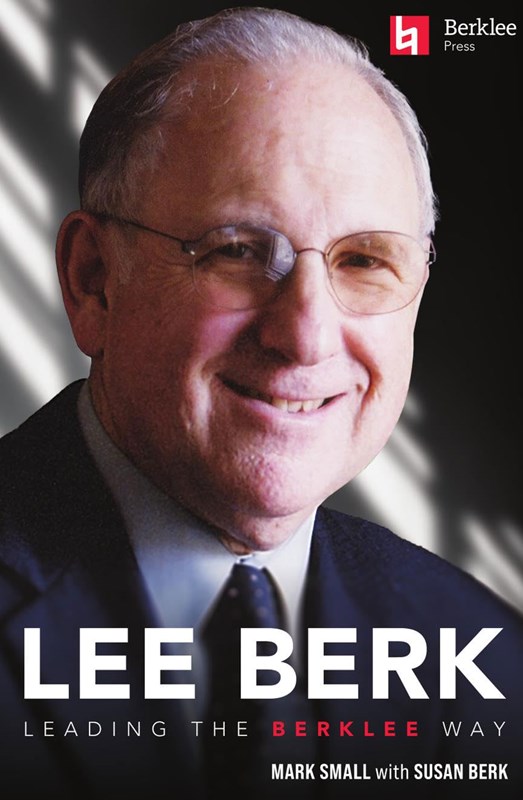

Lee Berk: Leading the Berklee Way

Mark Small / Susan Berk (Berklee Press PB $29.99)

When the pre-teenage Lee Berk saw his father’s Boston music school renamed after him in 1954, it must have seemed like destiny. Previously the school was called Schillinger House because they employed the musical theories of deceased composer Joseph Schillinger, who taught – among others – George Gershwin and Glenn Miller. It was not long before young Lee became involved in running of the school, which officially became a college in 1973, but it wasn’t until 1979 that Lee’s father retired and Junior took over as president.

Although this is nominally a biography of Lee Berk and his family, it provides a detailed history of the college, whose expansion was continuous from the 1950s. Though readers of this magazine will think of its jazz alumni – such as Gary Burton, Quincy Jones (from the Schillinger period) or Joe Zawinul – they’re in the minority. Though Mike Gibbs gets an honorary mention as their first artist-in-residence, things took off after Burton joined the teaching staff and encouraged the addition of rock music, then film scoring and music technology. Subsequent developments included Berklee Online and the development of Berklee International Network, partnering with music schools in Europe and elsewhere.

The fact that all these changes were actively encouraged and facilitated by Lee is attributed in comments from multiple sources to his co-operative personality and his supportive management style, which were rather uncommon in situations related to the music business.

The book’s direct writing style and apt quotations result in superior journalism by main author Small, himself a former Berklee guitar student. Clearly, if you wish to see the college’s approach or their priorities questioned, this is not the book for you. But, as an extremely competent biography, it also has great interest in terms of its musical outcomes.

Brian Priestley

Mbaqanga Nights

Leonora Meriel (Granite Cloud PB £8.99)

Leonora Meriel was born in London and lived in Ukraine. But this novel is set in 1989, during the dying days of the apartheid regime in South Africa, where music and politics converge.

Protagonist Laurence Jude opens a jazz club with his friend Albie in Durban, but his motive is more than just a love of the music. For wealthy Laurence, whose Jewish-Ukrainian grandfather came to South Africa decades prior, opening the club is also his way of “giving back”; he is aware of the repression and racism of the apartheid state.

But at a time when South Africa was widely considered the most racially segregated country in the world, opening a place where people of all races could mingle and enjoy music together is risky (in fact white and black mixing was illegal), Laurence persists; ‘Mbaqanga’ music, with its blend of Harlem jazz, swing, and American blues, is the perfect draw for a diverse crowd of people championing an end to National Party rule.

As the story jumps back and forth in time from the protagonist’s grandfather’s Ukraine to his present-day Durban to his future London, Laurence draws parallels between his family’s struggle and that of non-white South Africans during apartheid.

Meriel’s prose is clear, has an easy charm and she’s a good storyteller. At times, characters and scenes are painted with too broad a brush, which can make them seem like pawns to relay the book’s message. But the author has an impressive knowledge of Ukrainian and SA history, giving the book heft and authenticity; and after a couple of chapters, patient readers should find themselves carried along, despite the sometimes jarring jumps in the narrative.

A well-told tale of the unifying power of music and resilience, Mbaqanga Nights is a recommended addition to any ‘jazz fiction’ library.

Kevin Whitlock