Share

Investors are beginning to rethink Britain’s long-term fiscal sustainability

We don’t need higher taxes. We need a better state

Rachel Reeves’ Autumn Budget will be a moment of truth

It will begin, as financial crises so often do, not with a bang, but a murmur.

A failed gilt auction. A modest rise in yields. A subtle but persistent shift in investor sentiment. No panic, no headlines – just the quiet sound of markets beginning to lose faith.

For years, Britain has indulged in a fiscal illusion. Ministers promised what they couldn’t afford. Civil servants massaged the assumptions. The Bank of England quietly underwrote it all. Cheap money, the legacy of interest rates held too low for too long, enabled bad habits. And for a while, the bond market played along.

But illusions don’t last forever. And now, the spell is breaking.

This week’s Mansion House speech by Rachel Reeves was a study in composure. The Chancellor laid out what she called a ‘national mission’ to rebuild the UK economy: regulatory reform, pension liberalisation and a fresh partnership with the City. ‘The financial services sector is absolutely critical to my ambitions for our country,’ she declared. ‘Regulators in other sectors must take up the call… not to bend to the temptation of excessive caution, but to boldly regulate for growth.’

The Square Mile took comfort. Markets edged higher. The tone was right.

But one question went unanswered: How do we pay for the British state as it now stands?

Behind the reformist rhetoric lies a deeper threat that regulatory tweaks won’t resolve. Britain is drifting into what economists call fiscal dominance – the point at which the debt burden is so great, and the cost of servicing it so punishing, that neither monetary nor fiscal policy remains truly independent. The Bank hesitates. The Treasury dithers. And markets begin to reprice the risk of lending to Britain.

The numbers are now impossible to ignore.

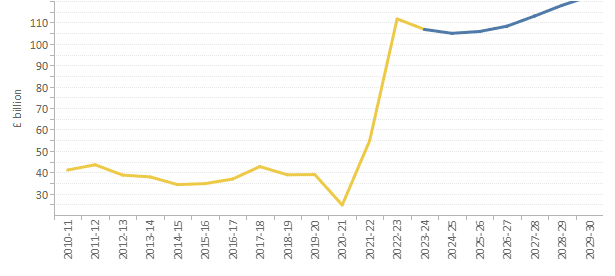

Debt interest payments are set to exceed £111 billion this year – more than 8% of total public spending, nearly double what we spend on defence. Roughly a quarter of UK gilts are index-linked, meaning every uptick in inflation feeds directly into the Treasury’s cost base. Meanwhile, the Bank of England still holds £589bn in government bonds, acquired during the QE binge and now being unwound at a loss. Those losses, thanks to a Treasury indemnity, fall not on Threadneedle Street but on the taxpayer.

Government net debt interest: latest forecast

Source: HMT, OBR

Then came the Office for Budget Responsibility’s Fiscal Risks and Sustainability Report. Tucked away on page 124 is a stark projection: if current trends persist, UK public debt could hit 270% of GDP by the mid-2070s. That’s not a G7 figure. That’s emerging market territory.

And the ground is already shifting. Pension funds – once dependable buyers of gilts – are gradually reducing exposure as they transition from defined benefit to defined contribution schemes. Meanwhile, the average maturity of UK debt is shortening, leaving public finances ever more sensitive to interest rate shocks.

The bond vigilantes are stirring. Gilt yields have risen steadily since spring. Not dramatically – but deliberately. Investors are beginning to rethink Britain’s long-term fiscal sustainability.

Yet inside government, the reflex remains the same: spend more, promise more, and hope growth catches up.

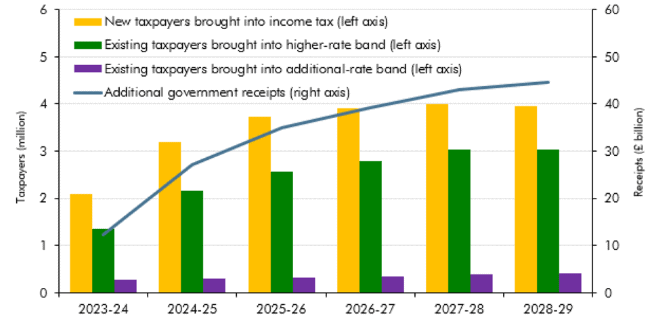

Public spending is now above 44% of GDP, the highest on peacetime record, and equivalent to around £45,000 per household. The tax burden is at a 70-year high. Productivity across public services remains stagnant at best. Reeves has ruled out increases to income tax, VAT or National Insurance. But not stealth taxes. Fiscal drag – the silent squeeze of frozen thresholds – is expected to raise £44.6bn by 2028, according to the OBR, most of it from middle earners.

Effect of tax threshold freezes

Source: OBR (originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – November 2023)

Meanwhile, the familiar chorus from those on the Left grows louder: tax wealth, tax capital more, tax ‘unearned income’. As if squeezing billionaires, or punishing success, can fix decades of bureaucratic sprawl and inefficiency.

But this is not merely a question of redistribution. It’s one of scale. Britain doesn’t need higher taxes. It needs a better state.

Smaller. Sharper. More accountable. A state that prioritises outcomes over inputs. That understands value for money. That abandons the fantasy that every policy challenge requires another cheque.

The danger now is that Reeves, like her predecessors, will try to muddle through, offering piecemeal reforms, carefully rationed rhetoric and hope that markets don’t notice. But markets don’t trade on sentiment or spin. They trade on price and risk. When they turn, they move swiftly – and without mercy.

We’ve seen this before. In the postwar decades, Britain managed its debts through financial repression. It worked – for a while. Then came the 1970s. Inflation soared. Growth stalled. Britain became the sick man of Europe. The clean-up took a generation.

Today’s version is more subtle – but no less dangerous. Inflation has cooled, but rates remain high. Growth is anaemic. Productivity is stalled. And the Treasury’s cherished ‘fiscal headroom’ has been hollowed out by U-turns and rests on interest rate forecasts that already look wildly out of date.

The Autumn Budget will be a moment of truth.

If Reeves wants to restore fiscal credibility, she must go further. That means reforming welfare to strengthen work incentives. Cutting waste. And confronting the sheer scale of the modern state. That means hard choices and honesty with voters.

There is still time. But not much. Because if she hesitates, the markets won’t.

And when they call time, there will be no second warning.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.

Columns are the author’s own opinion and do not necessarily reflect the views of CapX.