When Shane Warne was first chosen for a representative Australian XI in 1991 with a view to him being given a Test debut, Australia head coach Bob Simpson was struck by the youngster’s lack of athleticism. He decided to keep him on after the other players had left for a solo session of fielding drills, “just to see how much out of nick he was . . . he wasn’t good”.

A week later at the Boxing Day Test against India at the MCG, Simpson and Ian McDonald, the Australia team manager, bumped into Warne, who was there watching the game with some mates. He had a beer in one hand and a pie in the other.

Warne was chosen for two Tests later in the series regardless, but Simpson must have known then that there was work to do, and it was to his credit that Warne realised quite quickly that he would not play much for Australia if he did not meet the demands of a hard taskmaster who did not tolerate shoddiness.

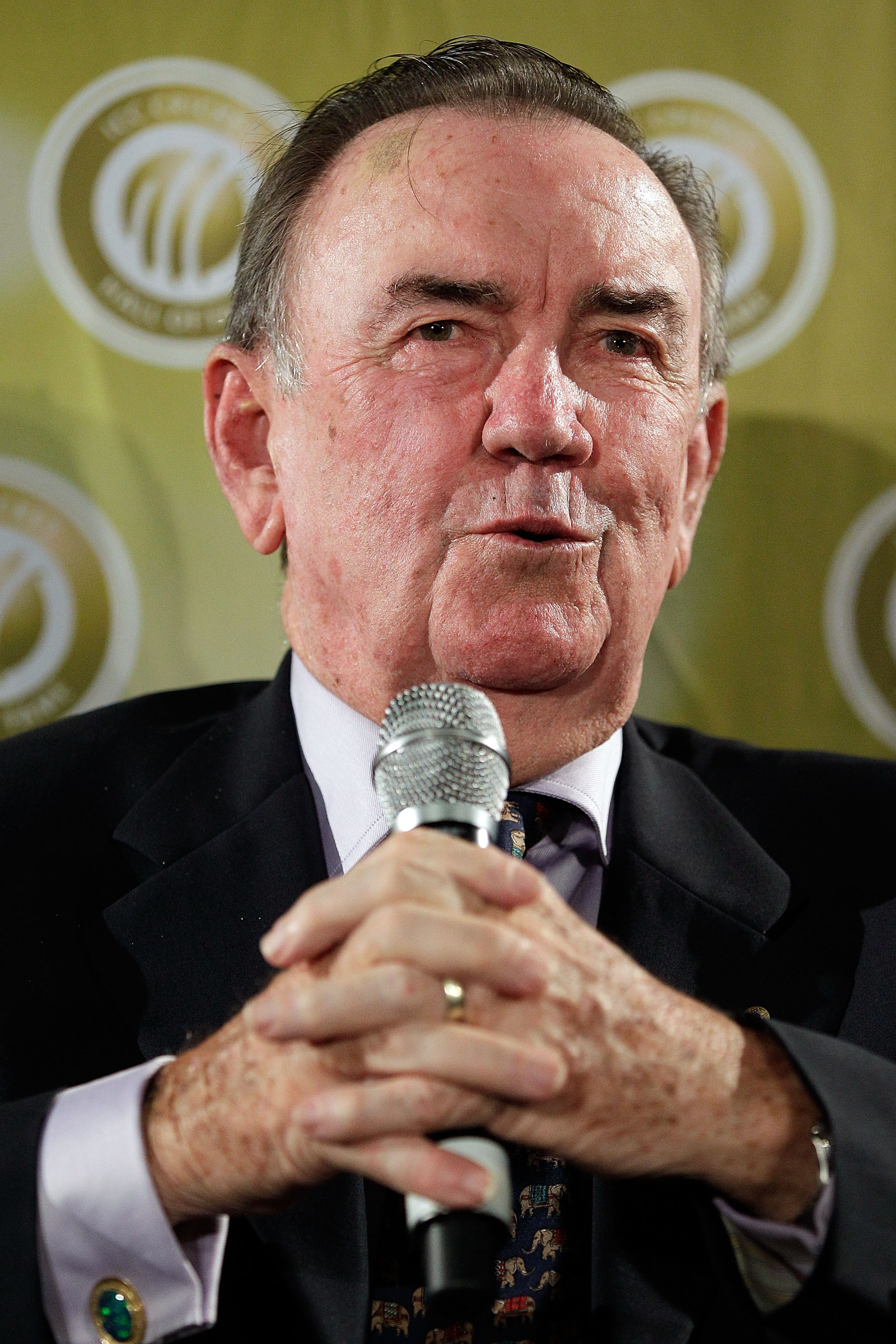

Simpson addresses his audience after being inducted into the ICC Hall of Fame in Sydney in 2014

BRENDON THORNE/GETTY IMAGES FOR THE ICC

Soon after, Merv Hughes, a Victoria team-mate of Warne’s, was not selected for a tour to Sri Lanka because he was not deemed fit enough, and this may have contributed to Warne — who was selected — turning up leaner and keener. “He was just a different person, physically and mentally,” Simpson recalled. After five gruelling days, Warne helped to win a tight first Test in Colombo — and the rest is history.

Simpson, who has died at the age of 89, was a seminal figure in the revival of Australian cricket during a ten-year reign as coach of the national team in which they won a World Cup in India in 1987, regained the Ashes in 1989 and retained them for the next three series under his watch, and in 1995 inflicted the first Test series defeat on the mighty West Indies in 15 years.

When Simpson took over in early 1986, Australia had been in the doldrums for a few years, broken in part by defections to a rebel tour to South Africa. Allan Border had been captain for less than 18 months and needed someone who could share his burden and provide the players with more structure.

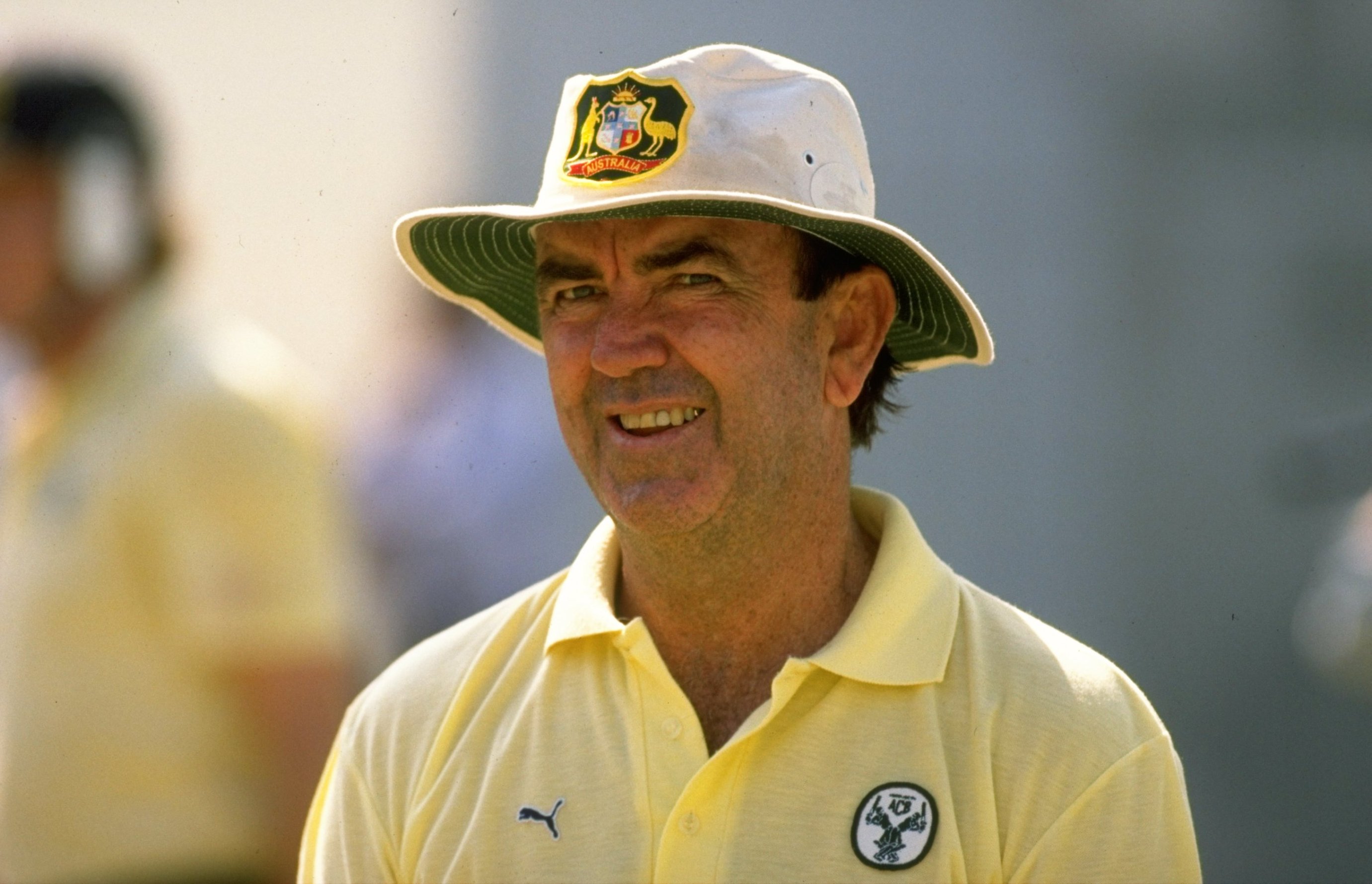

Australia players stand in silent tribute to Simpson before the T20 international with South Africa in Cairns on Saturday

SAEED KHAN/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Simpson was just the man. “I’m not sure who got the bigger shock during the first couple of training sessions,” Steve Waugh, one of Simpson’s most enthusiastic disciples, recalled. “Simmo, due to the team’s low-intensity work ethic, or the players, who had never been exposed to his level of passion at practice. Early on, there was a lot of complaining, [but] you had two choices: embrace and enjoy, or disregard and disappear.”

Before Simpson, national teams did not really have head coaches; they had managers who organised hotels and flights, and kept a schoolmasterly eye on their charges. Training sessions were run by senior players and strategy was left to the captain.

But Simpson’s impact was such that England quickly followed suit by appointing Mickey Stewart to a similar role, just in time for Stewart to help Mike Gatting’s team win in Australia at the expense of Border and Simpson. It would be 18 years before English cricket enjoyed such a triumph again — home or away.

As Australia got better and better, there was less need for Simpson’s disciplinarian style and technical input. The ruthlessness became so deeply ingrained in the likes of Waugh — who credited Simpson with developing his game more than any other person — that he outlived his usefulness. The players needed a lighter hand at the tiller. Simpson departed after Australia’s defeat in the World Cup final of 1996 at the hands of Sri Lanka.

“The total absence of a farewell to Simmo from the ACB [Australian board] after he lost the coaching job was a disgrace,” Waugh wrote in his autobiography. “From out of the abyss in the mid-80s, he left the twin legacies of increased professionalism and a winning culture, which were to be the hallmarks of future Australian teams.”

Simpson also had coaching spells with Lancashire and Leicestershire, and also worked in India, Nepal, China and the Netherlands.

Simpson makes 102 for the Australians in Barbados during a tour match in 1978

PATRICK EAGAR/POPPERFOTO VIA GETTY IMAGES

Long before he coached, Simpson enjoyed a distinguished Test career as a tenacious opening batsman — forming a weighty opening partnership with Bill Lawry — superb slip catcher, and part-time leg spinner. First chosen for New South Wales at the age of 16, he played 52 Tests between 1957 to 1968, when he retired relatively young at 32, before being lured back into service during the Kerry Packer crisis to lead a denuded Australia team in ten Tests against India and West Indies. Scoring 738 runs, more than anyone else in the side, he showed he had lost little of his skill.

He led Australia to victory in England in 1964, when he scored 311 in an absurdly high-scoring draw at Old Trafford — remarkably the first of his ten Test centuries in his 52nd innings — and oversaw the retention of the Ashes in Australia in 1965-66.

Amazingly, he was involved in the only two tied Test matches in history, first as a player in the match against West Indies at Brisbane in 1960 and then as coach against India at Chennai in 1986, a game in which a double century by Dean Jones in searing heat epitomised Australia’s tough new approach under Border and Simpson.

He stands as one of the most consequential cricketers Australia has ever possessed.