The women’s game has come a long, long way since the inaugural World Cup was played in Wales in 1991. Many of the 12 competing nations did not have the approval of their unions at the time, and it would be another seven years before the [then] International Rugby Board gave the tournament its official blessing. Heck, players from rugby-mad New Zealand even had to travel to the UK under their own steam because of the lack of sponsorship from the NZRU.

The USA beat England 19-6 in that final in Cardiff but the Red Roses returned the favour in Edinburgh three year later. The huge potential latent in the women’s game had yet to be recognised, and nothing illustrated that better than the curious fate of the World Cup trophy itself. After a brief sojourn in the world rugby museum at Twickenham, the ‘crown jewels’ promptly disappeared for the next 15 years before turning up in an attic during a bout of spring cleaning.

One of those 1994 World Cup winners, Gill Burns, feared it had been “melted down somewhere” and sold on for neat profit by a scrap metal merchant.

After 15 years it’s finally been found!

The story of how the first women’s Rugby World Cup trophy was found 🏆 pic.twitter.com/dAY2PYY9Ff

— England Rugby (@EnglandRugby) October 21, 2021

“It was in the museum briefly before it went back out on tour again and then a few years later we started asking ‘Does anyone know where the World Cup is?’ – and nobody knew where it was,” Burns told BBC Radio 5 live.

“I used to point at it at the museum and say ‘here it is girls, that’s something for you to aspire to!’

“One of the administrators ended up with the trophy at her parent’s house. All the old minutes of meeting and handbooks had been stored in a box along with [another] that had the World Cup in it.”

That was typical of the lack of seriousness with which the women’s game was viewed at the time. It was mothballed like an old relic, and it would take a few years to dust it off, polish it up and discover its true value.

In light of more recent developments, that must seem like nothing more than a rather quirky bad dream. When New Zealand began to take the World Cup seriously, winning six of the next seven quadrennial tournaments, other nations swiftly fell into line behind them.

England’s Red Roses have dominated the Women’s Six Nations (Photo by David Rogers/Getty Images)

England’s Red Roses have dominated the Women’s Six Nations (Photo by David Rogers/Getty Images)

The next milestone was the award of fully-professional contracts to the top 28 English women players by the RFU in January 2019. That New Year’s bonus was followed by the formation of the first fully professional domestic league, with ‘Premiership Women’s Rugby’ [PWR] kicking off with nine foundation clubs in the autumn of 2023.

Now women’s rugby is big business. By the middle of May 2025, over 300,000 tickets had been pre-sold for the tournament which begins on Friday, 22nd August at the aptly named Stadium of Light in Sunderland. That is already more than double the actual attendance figure for the entire 2021 competition in New Zealand. To cap it all off, World Rugby unveiled a gleaming brand-new trophy on BBC Morning Live which has performed its very own lap of honour, like an Olympic torch, around the eight host venues prior to the start of the tournament – Brighton and Hove, Northampton, Exeter, Bristol, London, Sunderland, Manchester and York.

At 38 centimetres tall and weighing 4.5kg, the new silverware is not to be meddled with, let alone forgotten – or worse, consigned to the attic. It is cast in sterling silver with 24-carat gold and nine world champion players from England and New Zealand helped design it. The sense women’s rugby is here to stay has been supported further by the legacy programme initiated by the competition’s managing director Sarah Massey.

“Once every four years we have this pinnacle moment where visibility and awareness of the World Cup and the players increases,” she said. “It’s an opportunity to make sure that is then taken forward from a long-term sustainability point of view to make sure we have more players, girls and women coming into the game.

“World Rugby’s ‘Impact Beyond 2025’ programme is all about supporting communities around the world, inspiring more women and girls around the world to pick up a ball and give rugby a try.”

If there is one obstacle standing in the way of that legacy, it is the depth of the competition. Despite roots grown by global professionalism over the past six years, there are realistically only four countries who can win the tournament: England, New Zealand, France and Canada.

The division between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’ begins much further up the scale than it does in the men’s event. In the latest World Rugby rankings, the range between the top eight nations is only 11 points in the men’s version, but it is more than twice that in the women’s game.

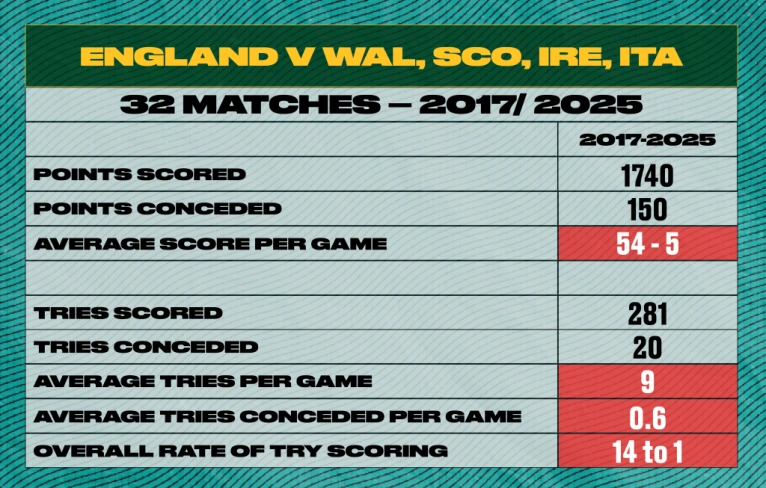

The issue was thrown into very sharp relief by a recent report on the Women’s Six Nations by World Rugby statistical consultant Corris Thomas. The problem in a nutshell is Ireland, Scotland, Wales and Italy are no more competitive now than they were before the advent of professionalism, in terms of their results against perennial top dogs England. In 2025, Thomas noted: “England scored a total of 213 points while conceding 29; produced an average score of 53-7; scored 33 tries and conceded five. Such a pattern has been consistent over the last eight years.”

The scores between England and all the other Six Nations countries bar France are remarkably similar, despite Wales, Ireland, Scotland and Italy all following England’s professional lead over the past four years. The average winning margin is holding steady at almost 50 points per game.

The most inconvenient truth of all is games were more competitive in the six-year period before 2017 than they have been over the past eight years. Between 2010 and 2016, England’s average winning margin versus the Celtic trio plus Italy was 33-6. Since 2017 it has been 54-5. Instead of catching up the Red Roses, the other four countries have been falling further behind.

It is Les Bleuettes who are responsible for making the Women’s Six Nations a true litmus test of England strength. Where England has won all 32 of its matches against Wales, Ireland, Scotland and Italy over the past eight years, France has won 28, with two losses, one draw and one cancellation, and an average winning margin of 36-9 against the same opponents.

They are also the only nation to have beaten the Red Roses [18-17 in 2018] within the same time-span. Even so, it was business as usual during the World Cup warm-ups. The Red Roses won the latest instalment of their series against France 40-6 in Mont-de-Marsan, extending their winning run against their Six Nations rivals to 16 games on the trot. 34 points represents the biggest margin of victory since the 2009 Nations Cup.

One of the other sides in the Six Nations needs to break out of the second-tier peloton and join the leaders.

Flip the coin over, and the biggest single upside of the women’s game is the continued rise of world number two-ranked Canada. The Canucks squad for the Pacific Four tournament in May featured a nice balance of 19 PWR-based players, 11 home-based, five from France and one in New Zealand. The women’s game tends to attract superior contact sport athletes because the comparable male attractions of football and hockey are largely absent. Rugby for women has an especially strong footprint at universities such as Alberta, Victoria and British Columbia, where female sport is funded on a 50/50 basis.

Canada is probably the only nation capable of competing on even terms up front with the Red Roses. A core of big athletic forwards such as prop DaLeaka Menin, second-row hybrid Laetitia Royer and back-rowers Gabby Senft and Karen Paquin give the Maple Leaf a hard physical edge and real athletic presence around the field. Canada backed up a 22-19 victory over the Black Ferns at the 2024 Pacific Four with a 27-27 draw at the same venue in Christchurch one year later. New Zealand needed a try with the clock in the red to claw their way back to a fortuitous draw.

Canada possesses genuine power in the set-piece and can drive short, or roll the ball away from the lineout into midfield with equal facility.

In the second and third clips, four members of the Canadian tight five, plus number seven Paquin, carry the ball deep into the Kiwi ‘A-zone’ before tighthead Menin finishes the move near the posts.

Canada used a dominant scrum platform to score another first-half try featuring their outstanding, rangy No.13 Florence Symonds, who contributed two key passes.

If there is one player who represents the indefatigable beating heart of Canadian women’s rugby, it is teak-hard, 37-year-old open-side flanker Paquin.

First Paquin and Royer set up the turnover at the tackle for Senft – one of eight at New Zealand rucks in the first half alone – before the number eight sets in motion a counter-attack with Paquin first up to deliver a bone-crunching hit on chase.

Canada have an 11-5-1 record since losing 36-0 to France in the third-place play-off at the World Cup in November 2022. Four of those losses have been to England, and the Red Roses will stand imposingly in the way of an historic first World Cup triumph for the Maple Leaf if Canada progress to the final.

Despite all the hype, the blue riband event in women’s rugby badly needs a new contender to challenge the big two of England and New Zealand. Hang on to your hats and hang on to the cup: it could just be time for the duopoly to dissolve, for women’s rugby to break another glass ceiling in North America.