The Leopoldskazerne in Ghent, sitting on the brow of a low hill above the green sward of Citadel Park, presents a faintly silly profile. It’s a sort of parody castle with its red brick and stone-dressed battlements and filials looking more Disney than defensive. Its eclectic and slightly pompous Neo-Renaissance overload of detail and architectural reference, typical for end-of-19th-century Europe, has now been set off against a very 21st-century makeover, featuring the new matt grey mansards and muted green-clad additions of a retrofit by Sergison Bates working with Belgian practices 360 Architecten and B2Ai Architects.

Built as a military barracks between 1890 and 1905, the original building replaced a simpler shed-like one, its fortified styling in part symbolically filling in for Ghent’s old citadel – demolished in the 1870s on an adjacent site, which is now the park – be it the walls here were built to keep soldiers in rather than invaders out.

Credit: Stijn Bollaert

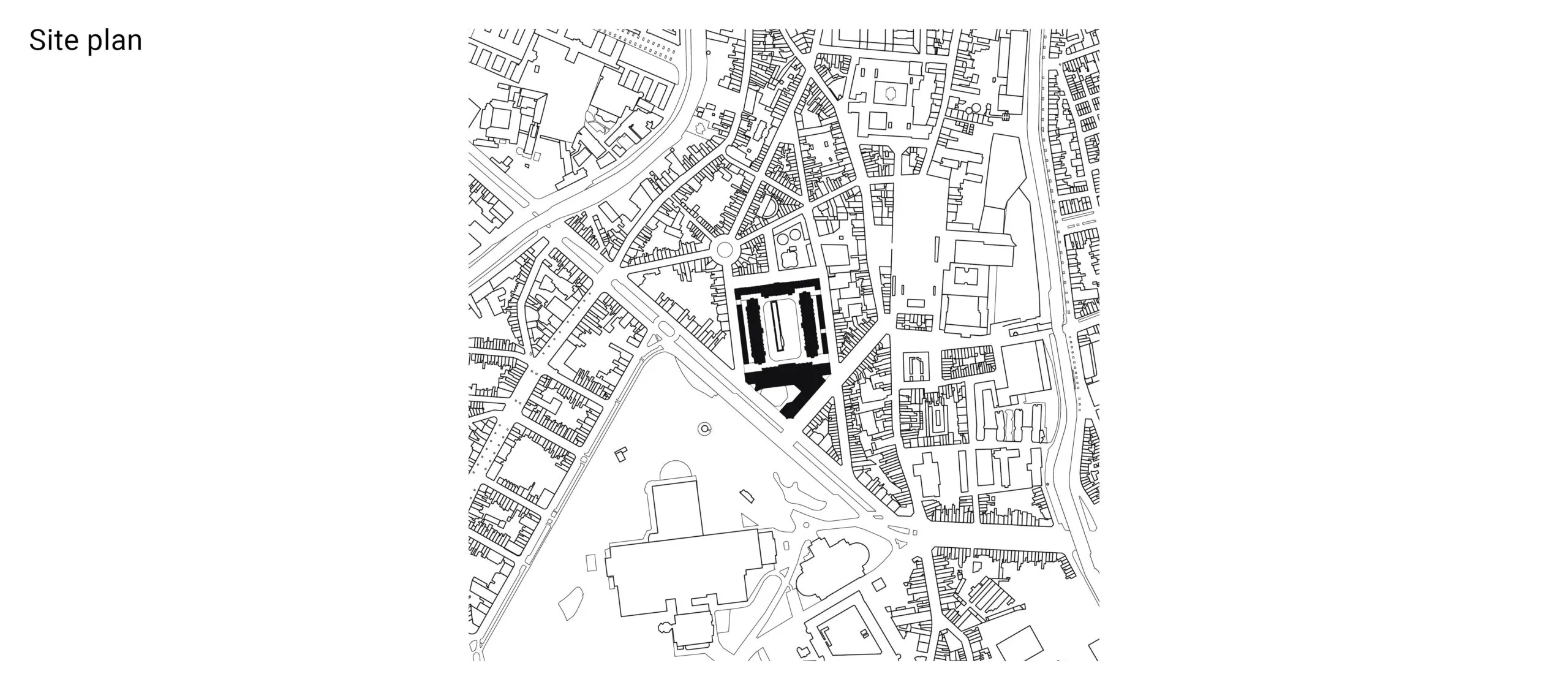

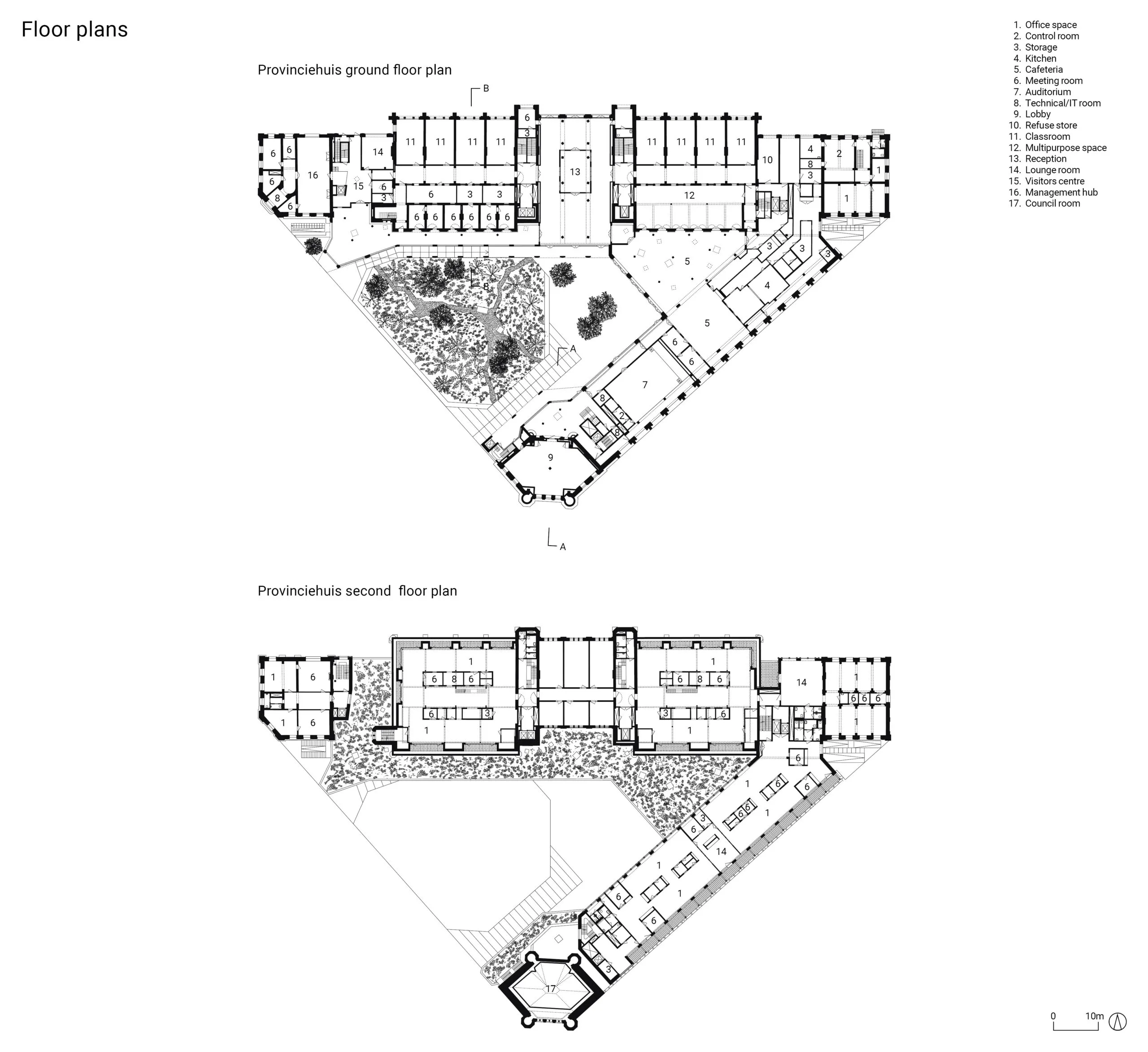

In contrast to its romantic skyline, the building’s original layout was symmetrical Beaux-Arts in plan. This consisted of a triangular complex of buildings enclosing a small courtyard to the south, facing on to a larger parade ground lined on three other sides by rectangular barrack blocks. The north side, facing the city centre, contained an arched main entrance.

The complex housed the military until 2007 when the site was sold to the city, but it seems that, unlike many military sites, nothing particularly bad happened here. Even when occupied by the Germans, it was used by the Luftwaffe rather than for anything more sinister. Most recently, it functioned as a centre for the medical training of recruits.

‘My dad remembers coming here,’ says architect Evelyne Vanhoutte. ‘Everybody’s dad knew it. It’s where you came to do your medical training for National Service.’

Credit: Stijn Bollaert

Vanhoutte is the associate at Sergison Bates who led on the adaptive reuse of the barracks into an administrative headquarters for the provincial government of East Flanders, Provinciehuis Oost-Vlaanderen, as well as 89 new homes, a creche, hotel, art school and adult education centre. ‘The brief was to reintegrate the site back into the city,’ she says. Though the military has also kept a foothold in the building with a recruitment office.

The project had its origins in a 2014 Open Call competition– the system through which public commissions in Flanders are awarded. This followed several years of the buildings’ occupation by meanwhile uses, including artists’ studios and an earlier incarnation of the art school. ‘It was a bit Hackney Wick-like,’ says Vanhoutte, who lived in London until last year.

The Open Call was later withdrawn by the client and changed to a design & build competition procedure in 2016 with a main contractor in the team. The site was divided between public uses (the Provinciehuis, art school and creche) and private ones (hotel and housing). The winning bid, Consortium THV Leopold, came from a partnership between developers DMI Vastgoed and Matexi, contractor Democo and the three architecture practices.

Credit: Karin Borghouts

The layout of their winning proposal accommodates the Provinciehuis in the triangular complex of buildings to the south, while the residential element is housed in the two symmetrical blocks to the east and west of the parade ground. The hotel and art school, meanwhile, occupy the original gatehouse building to the north.

The adaption required the demolition of several later additions – including a gym and other shed-like buildings occupying the courtyard – and the removal of chunks of battlemented perimeter wall in order to make the site more permeable and connected to the city – a process the practice describes as ‘repair, cut and fill, extend’.

‘It’s valuable heritage but not a protected monument,’ says Vanhoutte, ‘The architecture needed both opening up and calming down.’

The ‘opening up’ is manifested most clearly in the removal of the south-facing stretch of courtyard wall, thereby creating a generous triangular forecourt to the Provinciehuis’s new entrance. The new entrance lobby links courtyard and parade ground, creating a public route through, while other new routes opened from surrounding streets at the corners of the parade ground make the site more porous still.

Credit: Karin Borghouts

The ‘calming down’, meanwhile, involved replacing most of the roofs with new mansards, which Vanhoutte describes as ‘abstracted’ versions of the originals. Meanwhile, the majority of additions are clad in delicately ribbed metal panels, a muted mint green in colour that recessively complements the red of the brick. These additions include a large block of administrative offices for the Provinciehuis to the south-west of the triangular forecourt.

The calmly orthogonal forms of these additions also act as a foil to the filials of the existing blocks. The same green is used for the frames of new roof-level mansard windows, while new windows in the brick barracks sport russet brown frames – matched to the original colour from the evidence of paint samples. Overall, it all serves to damp down the busyness of the original architecture rather than create more contrast with it.

This calibration of form and colour for the new-build elements reflects the site-wide ‘detail guidelines’ developed by Sergison Bates working with the other two practices. Sergison Bates then worked with 360 on the detailed design, fit-out and build of the ‘public’ Provinciehuis, which recently completed, while B2Ai led mainly on the ‘private’ elements: the housing blocks and hotel around the parade ground (the latter still to complete).

Credit: Karin Borghouts

In general, the interventions comfortably contrast with the original, exhibiting a consistently high build quality given this is a developer-led, design-and-build project, although they look less light touch than in the original competition-winning visuals, which depicted them more armature-like, recalling the work of disbanded Ghent practice Architecten de Vylder Vinck Taillieu.

New-build elements appear less sure-footed, though, when designed to echo the brick and stone of the original. B2Ai’s deft rework of two outer perimeter walls into short terraces of houses is let down by block-like brick upper storeys, baldly bulky in form.

Similarly the entrance to the recently completed Provinciehuis – the main focus here – is via a new concrete colonnade, which provides a port cochère and covered passage and from the street, but which stands out awkwardly against the buildings it’s designed to link.

It means the entrance forecourt, with its line of flagpoles sporting East Flanders and EU flags, speaks more conference hotel than public facility.

Asked about the choice of concrete, not least given its high embodied carbon, Vanhoutte says it was to give a solidity appropriate to the original buildings. She points out that the relatively low 107 kgCO2eq/m2 embodied-carbon figure for the whole project – despite the significant additions – is reflective of how most of the existing structure was retained.

Credit: Karin Borghouts

Given this a-priori retention of fabric, the focus here has unsurprisingly perhaps been on reworking and extending this to enable new uses. This is demonstrated not least by a massive three-storey basement sunk under the parade ground – with all the carbon-hungry excavation and concrete this implies – which accommodates on its upper level all the facilities and garaging for the local authority’s maintenance department and its vehicles. It also contains capacious bike stores and extensive bike repair facilities – for civil servants and residents alike. Two further floors below offer parking, incorporating extensive electric charging points.

The environmental emphasis here has been on the operational upgrade of the building and site, including 70 per cent on-site energy generation via air-source heat pumps and PVs, in what Vanhoutte terms ‘a green plan of approach to the historic ensemble’. This is very literally flagged on arrival by the extensive planting of the forecourt and parade ground (previously a car park) – the former providing a lush backdrop to a terrace spilling out from the main cafeteria, the latter cut by a diagonal slash of sunken court, which serves the maintenance department below as both lightwell and amenity space.

The fabric upgrade of the building envelope has been forensically tailored to different conditions, with the solid yet porous brick façades insulated from inside and treated differently depending on orientation and exposure. To the north and east, a vapour-permeable mineral insulation has been installed together with façade heating, activated only during sub-zero temperatures, protecting brickwork from frost damage.

Credit: Karin Borghouts

The main entrance lobby has a reception pod sitting at its centre and is lined with perforated brick, which incorporates both acoustics and ventilation. To the left, an internal passage, lined by bench seating and running parallel to the colonnade, has small intimate ‘chat’ rooms opening off it – bookable for meetings or by citizens seeking advice. It terminates in a larger event space, again bookable by the public, where the colonnaded structure widens out into an expressive prow overlooking the park – a rare non-orthogonal new-build moment.

The internal finishes see the patched and faceted surfaces of the original building both emphasised and taken back by limewash. Set against this are simple, often rhythmic, new elements and surfaces, indicating a calm reordering: from grey ribbed timber doors to a serried line of acoustic ceiling baffles that shield and reveal the exposed services behind. Variegated red quarry floor tiles, meanwhile, ground and warm up the whole. Everywhere the fit-out uses simple robust materials and products to straightforwardly make the architecture. ‘The overall aim was to calm and tone things down, but warm them up in places too,’ says Vanhoutte.

This approach continues across other spaces. A large cafeteria sits to the right of the lobby – intended for civil servants and public alike – with a similarly quarry-tiled floor, and acoustic-baffled ceiling together with curtains and fabric-covered screens providing further acoustic damping and separation between the upcycled timber tables.

Credit: Karin Borghouts

Vanhoutte says the overall layout was conceived as a series of thresholds between fully public areas, regional government offices and shared facilities. The latter include a 200-seat auditorium positioned beyond the cafeteria, one of a series of rooms hireable for conferences. The fit-out here is taken up a notch, with robust on-edge oak flooring and a slightly fizzier palette of green curtains and upholstered tiered seating.

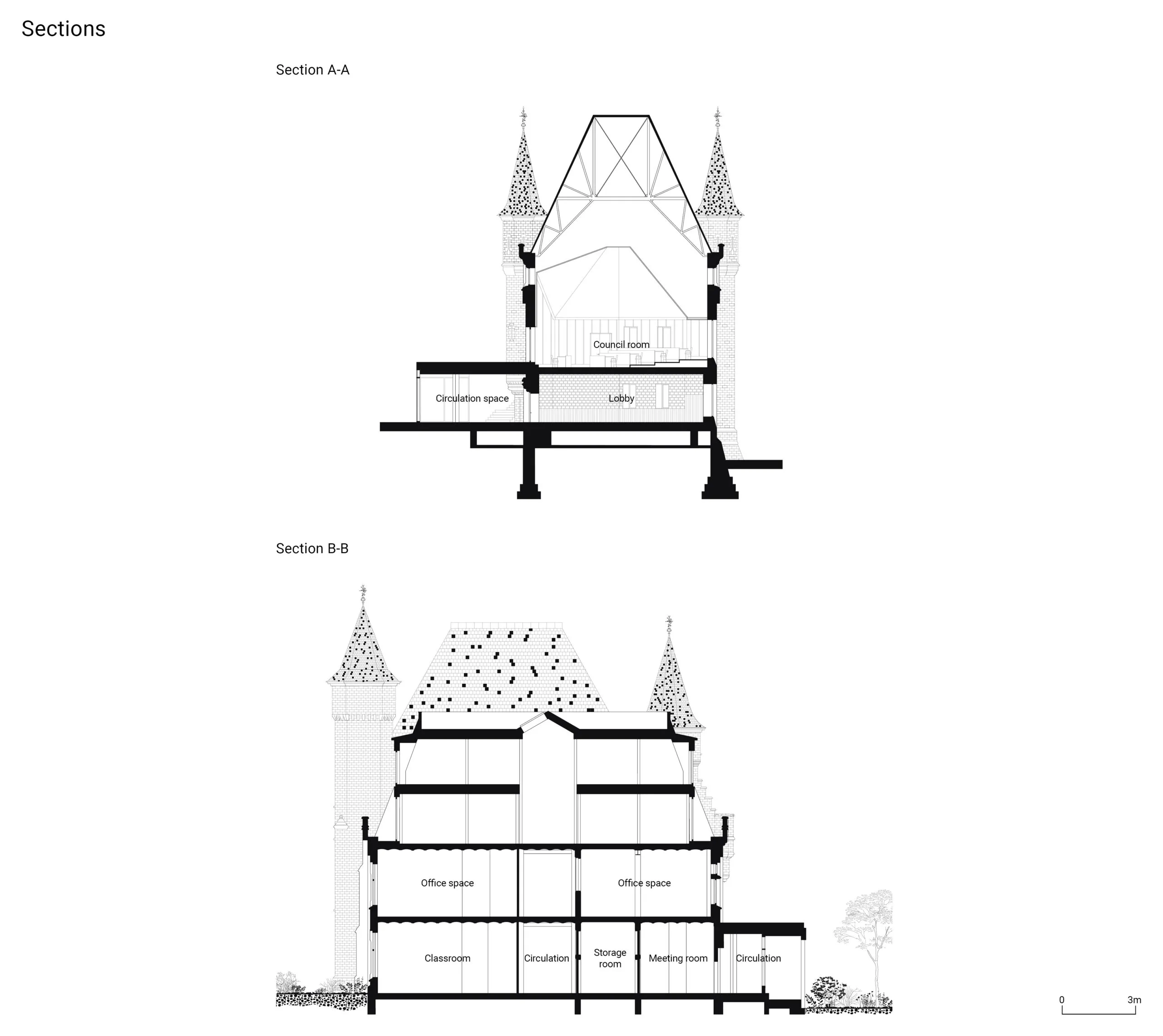

Beyond this is the building’s main focus: the East Flanders’ chamber of deputies occupying the first floor of one of the turrets. Its faceted ceiling, rising to 9m, echoes in abstracted form the mansard roof above and has been reinforced by steel trusses. ‘It’s meant to be tentlike,’ says Vanhoutte. The colour and fit-out here have been taken up a further rung, with oak detailing and surfaces painted a deep mustard-olive – ‘we wanted a pungent but non-political colour,’ she explains.

A portion of the ground floor around the entrance lobby and the first floor above it accommodates an adult education centre, its classrooms carved from larger former dormitories, through pragmatic demolition and repositioning of walls. This has created a double bank of well-sized, well-lit rooms to either side of a wainscoted central corridor. Along its ceiling run all the technical services so as ‘to keep rooms calm’.

Credit: Karin Borghouts

Above this, reconstructed mansard roofs house regional government offices. Arranged in duplex ‘neighbourhoods’, as Vanhoutte calls them, desk spaces sit adjacent to windows around a central core of meeting rooms, kitchenettes and lockers, which are double-stacked around a balconied double-height space containing the stairs. Boldly patterned carpet tiles, designed ‘to break up scale’, add to a rich but muted colour palette of oxblood, green and grey, in similar vein to that seen elsewhere.

The bulk of offices are accommodated in a large new-build element across the courtyard, where eight-desk clusters, each with a kitchenette, are arranged horizontally, benefiting from terraces perched above the battlemented wall overlooking the street to the south. These, again, are ordered around a pragmatic fit-out language created by acoustic linings, services and furniture. Islands of climate ceiling panels lend the kitchenettes a distinctive identity, while walls of lockers provide buffers to quiet areas. Indeed the all-of-a-piece fit-out with its controlled colour palette makes the spaces look somewhat like Thomas Demand models.

In all, this is a refreshingly pragmatic retrofit with none of the fetishising of the building’s history seen so often now. It’s a straightforward repurposing and operational upgrade of its fabric to enable it to function sustainably into the future. Using a language not of layering and palimpsest but of abstraction, subtraction and calm, it gently returns a civic role to this prominent building.

Credit: Karin Borghouts

Architect’s view

Located in the Arts Quarter of Ghent between Sint-Pietersplein and Sint-Pieters Railway Station, the 2ha site contains the former parade ground, one of the largest squares in the city. Our primary objective has been to reimagine this space and connect it to the existing network of public spaces. We conceived it as a piece of infrastructure that can be reconfigured according to changing programmatic needs, both during the design process and after its completion.

The existing monumental buildings are characterised by thick perimeter walls, battlements, corner towers and embrasures. Our brief was to open up this prominent but impenetrable stronghold and transform it into an open, welcoming place. We approached it with an acceptance of the building’s powerful identity as a landmark and its layered history. In addition to the East Flanders provincial government headquarters, the project accommodates a broad range of uses: a hotel, the HISK art school, a centre for adult learning and professional development, a community creche, 80 apartments and nine family houses, and flexible spaces with just a base fit-out.

Organising the very specific requirements of the brief within the existing structure required a clear conceptual framework for renovation and transformation. We applied a strategy of ‘repair, cut and fill, extend’ to the building’s exterior. Internally, our strategy relied on ‘repair, infill, linings, installations’.

The traces of this reorganisation of spaces and surfaces remain visible. The juxtaposition of old and new is a powerful memento of the former lives of the building that gives a complex, unfinished quality to the whole.

Stephen Bates, founding partner, Sergison Bates architects

Client’s view

By choosing the Leopold Barracks site for its central headquarters, the Province of East-Flanders underscores its commitment to sustainability and heritage conservation. The aim was to transform this closed military complex into a future-oriented, lively urban quarter, using sustainability, flexibility and heritage preservation as the key guiding principles.

The formerly fully paved site has been transformed into a green, accessible urban neighbourhood, with the Paradeplein – a sizeable neighbourhood park on top of three underground levels housing logistics, storage and car parking – as its vibrant heart.

The Provinciehuis, along with this neighbourhood park, a nursery, housing, and a hotel, make up a new, sustainable and inclusive city district. New additions link the historic pavilions – their architectural appearance subtle and in harmony with the historic buildings. A flexible design approach allows spaces to be easily adapted to future needs, while the technical installations are modular and adjustable to future technological developments.

Certain parts of the Provinciehuis remain open to the public, like meeting facilities, classrooms and the restaurant and cafeteria.

The project was realised through a design-and-build procedure, including a three-year maintenance contract.

The Provinciehuis has achieved a BREEAM Excellent rating — a strong endorsement of the comprehensive sustainability approach, in which environmental responsibility, user comfort and social encounter go hand in hand.

Kristof Goethals, director of logistics, Province of East-Flanders

Conservation consultant’s view

As heritage specialists, we approached this project as a restoration with a significant architectural complexity. The greatest challenge lay in dealing with severely deteriorated building components and historical damage without compromising the heritage value. Many valuable building components were seriously degraded, for example brickwork in poor condition or natural stone showing war damage.

The cement render added on the rear of the battlements had disrupted the natural moisture regulation which, over time, caused accelerated deterioration of the clay bricks. As a result, parts of the brickwork required complete reconstruction. We chose new bricks in appropriate colour tones, carefully composed to resemble the historic battlements. Natural stone components – often damaged or missing – were locally repaired with hydraulic repair mortars, new inserts, or, where necessary, fully reconstructed based on existing models.

The pointing had decayed or been washed out in many areas and was entirely replaced with a vapour-permeable hydraulic lime mortar. The plinth course in grès des Vosges natural stone also required full repointing. Severely damaged stones were replaced with on-site reclaimed material, sourced from the demolished perimeter buildings.

The reuse of historic elements, such as gargoyles, downpipes, rainwater heads and wall anchors, required careful selection and reinstatement.

Authentic historic elements were grouped around the central Paradeplein while new reconstructions were installed in less visible locations, thereby strengthening the heritage value of the building complex without compromising its integrity.

This restoration proves that architectural interventions and heritage conservation can go hand in hand – provided there is thorough analysis, skilled craftsmanship, and an integrated vision.

Arnout De Schryver, project manager and partner, Spectra, formerly Architectenbureau Maarten Dobbelaere

Engineer’s view

When you are allowed to design from a clean slate, there are certain conceptual choices that you make as an engineer to avoid needless complexity. Starting from a building with historic value is a very different story.

Looking back, one of the key challenges was the optimisation of building space in a complex environment of existing foundations. It was essential to have a detailed overview of the foundations for both the calculations of the existing buildings and the interface with the underground parking space. The proximity of pile walls to the existing foundations proved insufficient; the new foundation walls had to be partially underneath the existing foundations. For this purpose, we proposed very high-pressure grouting to create the walls directly under the foundation of the towers. The complete excavation of three underground levels added to the complexity of the task.

One of the main architectural highlights is the hexagonal corner building where the council room was located. To achieve the open space that was required for the architectural vision, the internal walls had to be demolished. These walls however were important structural elements for the horizontal stability and the vertical load bearing of the historic steel roof. This entire operation was carried out in multiple phases where new concrete columns were constructed and combined with a plethora of steel profiles and custom connections to support the existing roof and masonry walls. Seeing the historic steel roof from the foundation level was a sight to behold.

Beau De Backer, senior project lead, Sweco Belgium

Working detail

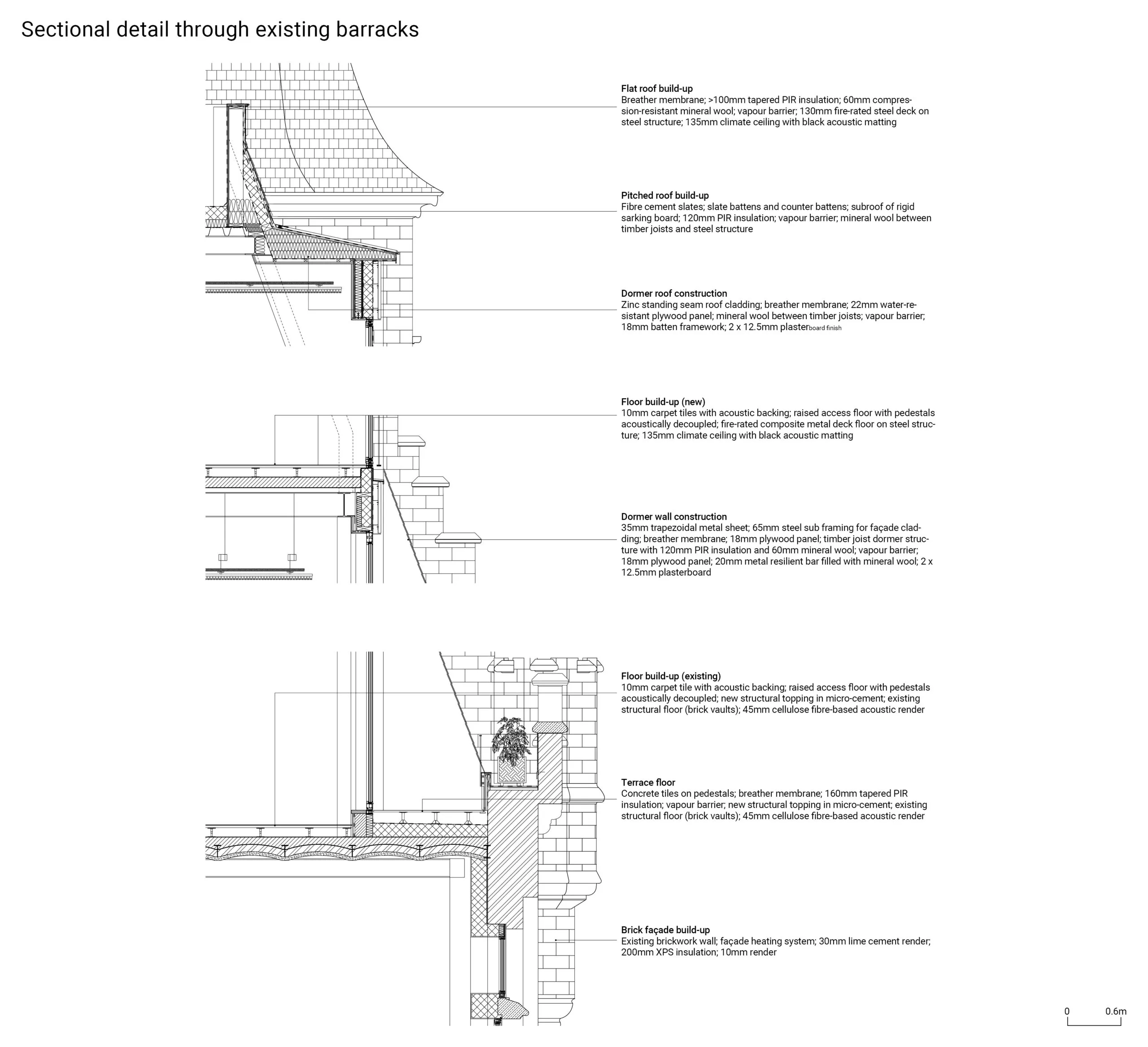

This sectional detail through an existing barracks building and its renewed roof with large dormers illustrates how we sought to intervene respectfully in a historic context.

A set of ‘detail guidelines’ was developed between the three architecture offices to guarantee visual coherence across the historic ensemble, while allowing subtle variations between the offices and buildings. These guidelines included formal agreements like roof and dormer shapes, brick bonds and repair strategies, as well as the colours of cladding materials and window frames.

The detail shows how the old mansard roof was completely reconstructed in a more abstract form. A lightweight steel structure sits on the bulky brick walls of the barracks building – a reference to the former steel roof trusses.

The sloping roof planes form a parapet that conceals the horizontal surface with PV panels from view. Double-height aluminium dormers maximise daylight entry into the formerly dark attic, now converted into office spaces. A climate ceiling system, suspended as individual islands above each cluster of desks, ensures a comfortable indoor environment.

The dormers lead to a terrace, situated behind the original parapet, which now functions as a wide rainwater gutter and holds planters. A new steel balustrade is set back from the edge to reduce its visual impact. The window frames are a subtle grey-green in new additions, and dark brown when set in the original brick façades – as seen in historic photographs.

The energy performance of the existing buildings has been improved by insulating the building envelope from the inside, leaving the historic solid brick façade exposed. A façade heating installation, activated only during sub-zero temperatures, protects the vulnerable brickwork from frost damage.

Evelyne Vanhoutte, associate, Sergison Bates architects

Credit: Karin Borghouts

Project team

Location: Ghent, Belgium

Start on site: January 2020

Completion: Provinciehuis: March 2024, creche: September 2024, housing phase 1: March 2023, housing phase 2: July 2025, hotel: August 2025

Gross internal and external floor area: Public programme (provinciehuis, creche, art school, garage): 38,500m2, private programme (housing, hotel): 22,375m2

Construction cost: €70 million

Architect: 360 architecten, Sergison Bates architects, B2Ai

Client: Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen

Structural engineer Sweco Belgium

MEP consultant: Ingenium

Acoustic consultant: Bureau De Fonseca

Conservation consultant: Spectra (formerly Architectenbureau Maarten Dobbelaere)

Landscape architect: Public programme: BuroLandschap, private programme: Delva

Sustainability and BREEAM consultant: DUSS-Explorers

Fire consultant: SECO

Ecology consultant: Antea

Sewage consultant: ARCH & TECO

Health and safety co-ordinator: V.E.T.O.

Principal designer: Public programme: Sergison Bates architects and 360 architecten, private programme: B2Ai

Main contractor: Democo

CAD software used: Vectorworks, AutoCAD, Revit

Sustainability data

Percentage of floor area with daylight factor >2%: Not calculated

Percentage of floor area with daylight factor >5%: Not calculated

On-site energy generation: 70% (via on-site heat pumps and PVs)

Heating and hot water load (gross): 33 kWh/m2/yr

Operational energy: 36 kWh/m2/yr

Total energy load: Not calculated

Carbon emissions (predicted): 5.9 kgCO2/m2

Annual mains water consumption: Not calculated

Airtightness at 50Pa: Not calculated

Overall thermal bridging heat transfer coefficient (Y-value): Not calculated

Overall area-weighted U-value (predicted): 0.376 W/m2K

Annual CO2 emissions (predicted): 5.9 kgCO2/m2

Embodied carbon: 107 kgCO2eq/m2

Whole-life carbon: 464 kgCO2eq/m2

Predicted design life: 60 years