When I get home, Granny announces me to everyone.

“Here’s our changeling, now.”

It’s her special joke just for me. I think it’s because I have recently gone from child to young woman; perhaps there is more to it, I won’t let myself be offended. Mother makes me sit at the table and eat dinner with everyone even though she knows I have already eaten, because I’m not supposed to eat at the chipper.

“Waste of money and waste of appetite.”

Mother says as she heaps boiled vegetables out of the pot and onto my plate. I struggle through the carrots and parsnips while she smirks. My perfect mother, a sweet and stinging honeybee. When I was a little girl, when I was very young and confused, just a small fruit fly bumbling around her kitchen, I refused to leave her side. Even at my small age, I understood that there were limits to love, and I felt sure that one day people would run out of love for me. I think with Mother, it started when I was in junior infants, when I received three slaps to the palm from Sister Loretta for playing kiss chase in the yard. Mother was always so smug over my good behaviour. Even today, she likes demure and cooperative girls. That day with my ruler marks was the first time she thought I might not be as easy to manage as I seemed. Granny said I must have done something awful to deserve it, because these things don’t happen without a good reason. But the truth was, I shouldn’t have been slapped, because I didn’t even want to play kiss chase that day. Without meaning to, I played the game and got kissed. How was I to explain all that? I couldn’t even say the word kiss in front of them, let alone explain the workings of kiss chase. Granny was so frustrated with me that she promised to slap my other palm until they matched, but it was an empty promise.

“Ah, dote, you’ll be better before you’re married.” Mother said, like she always did, although for the first time her tone was weary. Besides that, all they did was send me to bed a half an hour early, where I lay on the freshly washed sheets and inhaled the smell of her detergent, and I felt her love in the pillowcase.

We have never been the type of family to argue; we feel things very strongly, but we feel them quietly. Our deepest emotions may be manifested in the lightest of sighs, but not much else. The silence says a lot. All that upset has to go somewhere; I sometimes feel it moving under my skin, waiting to be lanced. One day, Mother will grow tired of me. This isn’t a worry or a guess, it is an instinct. Her affection will wane, and so I must absorb all the love she gives me while she is giving it. She was never annoyed by me staying so close to her in the kitchen. Granny used to threaten to put me on the back doorstep if I didn’t stop following Mother around. She used to say,

“If we leave you out there for the night, another mammy will come along and take you away. We’d have no trouble then.”

Many times, Granny would open the door and point to the step and slowly count to three, but I was never actually put outside. Mother wouldn’t allow it. All I wanted was some company, to be one of the grown-up girls. I never thought I was being a pest until I was made aware I was one. Whenever Granny gave out to me, Mother would scoop me up, and with a little groan, she would sit me on her hip, and she would say,

“Sure, Lucy is my little helper. There’s no one who helps me as much as this one! Oh, but you’re too big to lift up anymore.”

Still she kept lifting me without being asked to, and I guessed that meant that I didn’t have to leave her alone. When I was a little girl, it was always like that. I was always welcome around Mother. I might even say we were inseparable. Now that I am getting older, it doesn’t matter whether I am right next to her or out of sight, I’m heavy in the air, I am something always on her mind, she cannot be without me, even when she is dying to be. Maybe I deserved it, maybe not.

After dinner, Martin comes over for my Irish lesson. Last year I dropped from the Higher Level class to Ordinary Level, and still I am falling behind. Unable to pay a tutor, Mother has enlisted Martin to come over and help me in the evenings. He does as she tells him. Isn’t that insulting? Granny used to try to help me out, but with her temper so short, it only made things worse. Martin is breezing through Higher Level Irish, so my curriculum is nothing to him. In the low and sleepy light, he sits next to me at the kitchen table and kicks me when he sees my attention fade. He is trying harder than usual tonight to keep me interested, as Mother can see us from the living room. She won’t look away from Glenroe for long enough to catch me daydreaming. He should know that.

Although it’s nice that he wants to help, I don’t think this is a fair way to teach me. Martin isn’t embarrassed about it, he thinks he is being helpful, and he is very happy about that. This deep into the summer, I just don’t see the point in homework. Whatever I learn now will be forgotten by September, I promise. Then I will be back in the classroom, not listening and not learning. I don’t know why I need to waste my evenings preparing for that.

After an hour of trying to teach me, he gives in and lets us play hangman in his copybook. It’s sweet that Martin wants to help me, it’s funny that he thinks he could hold my attention. I like sitting at the table with him, with the evening air coming in the window. He never makes me feel upset or stupid when I can’t keep up with schoolwork. He makes me feel grounded. While I’m trying to work out which letters are missing, he tells me how cool he thinks my new jacket is. I don’t bother telling him that the jacket he saw me wearing today was Susannah’s and that I was only trying it on. It’s the compliment that counts. I don’t think he looked much at the jacket, but he definitely saw me admiring myself in it. He is attentive in ways that the girls aren’t. I want him to know I appreciate it, but I don’t want to have to say anything about it.

When he leaves, I watch from the back door as he disappears down the garden, out onto the dark road, taking the last of today’s goodness with him. Then I am left alone with my family. Mother comes downstairs in her dressing gown to take a painkiller. Something about Mother in her nightdress puts me on edge. She tells me to turn off Ciarán’s lamp when I am going to bed and leaves me alone again. I hate the quiet of the sleeping house, especially after a day out with my friends. The silence rings. It makes me feel so much more isolated than I really am. I ought to go to bed before I have a chance to do too much thinking. I linger at Granny’s door as I pass. When I was young, I would always go in and say goodnight to her. A big part of me wants to go in and do that now. Instead, I go upstairs and convince myself that she is probably asleep. As much as I like getting older, parts of it make me feel guilty and uncomfortable. I brush my teeth and knock a lump of dried toothpaste off the edge of the sink. I don’t know if it’s me or the mirror, but my face looks too long. It’s my hair, it doesn’t suit me at this length. I should cut it short again. That was flattering, but that was not very feminine. The girls all have long hair, even the boys have long hair. I want to look like all of them. I could look at myself in the mirror all night. In bed, I hear water run through the pipes. The immersion timer clicks off, and the house exhales. Today is over, and we have a few hours before we must start again.

Although we don’t discuss it, the girls had similarly melancholic evenings to me. Patricia went home to a darkened house, just the glow of the television on her parents’ worn-out faces to let her know that anybody was there. The volume was very low, their phone might as well be disconnected for all the use it gets. Eimear’s house was alive with the choir of her young siblings crying over bath time. Her mother did not notice as she came through the door and trudged up the stairs to her bedroom. As Susannah made her way up the steep driveway of her house, Croft Hall, she saw her father’s car gleaming in the evening light, and she heard her mother shouting. When she got inside, Catríona slammed her bedroom door, and Phil threw something heavy at it. He is not a big man, but he uses every ounce of the weight he has. Normally he would only visit when Catríona is not around. The rest of the time he spends with his shining new family in the city. Susannah didn’t bother asking him why he was in Crossmore.

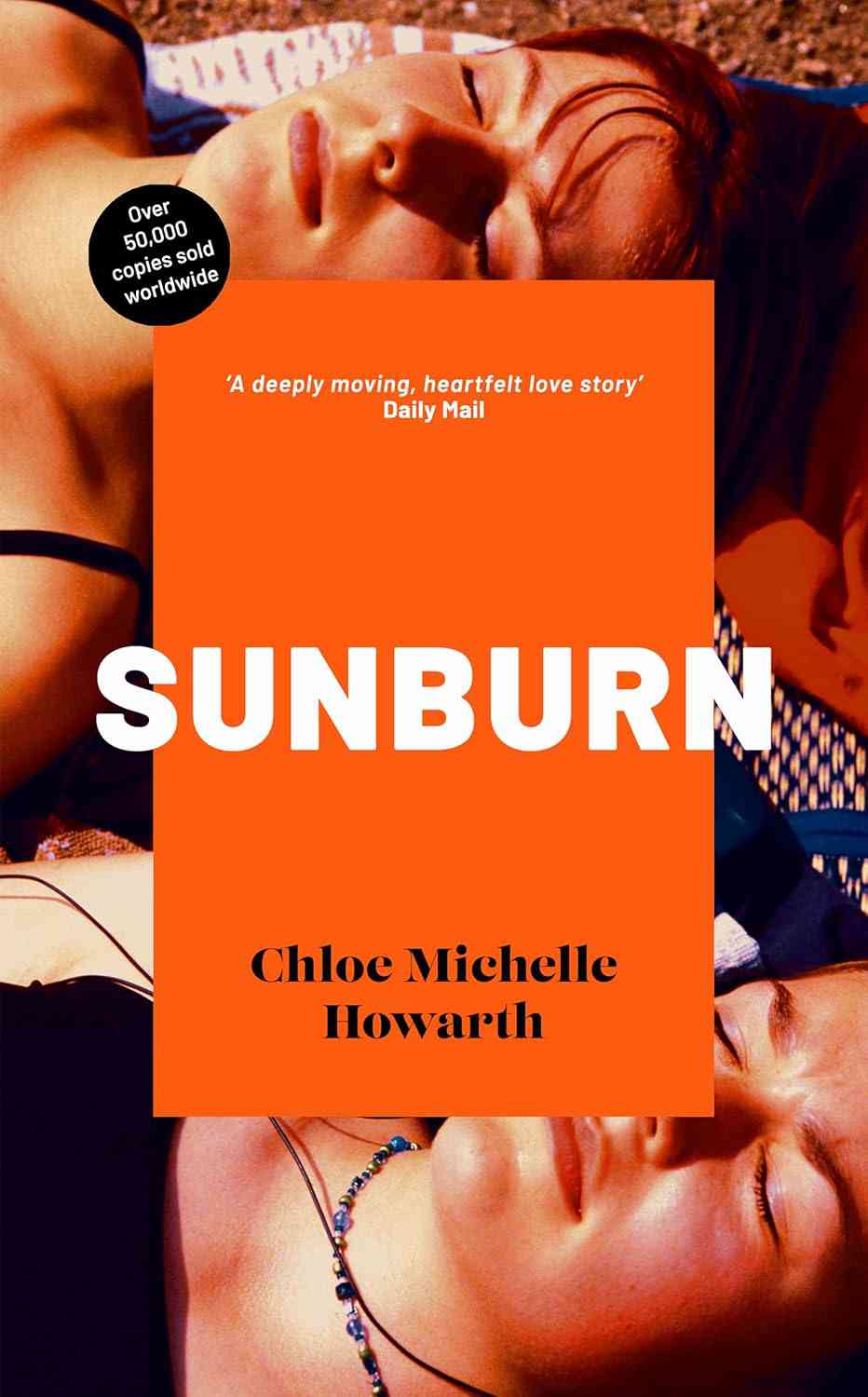

Excerpted with permission from Sunburn, Chloe Michelle Howarth, The Bombay Circle Press.