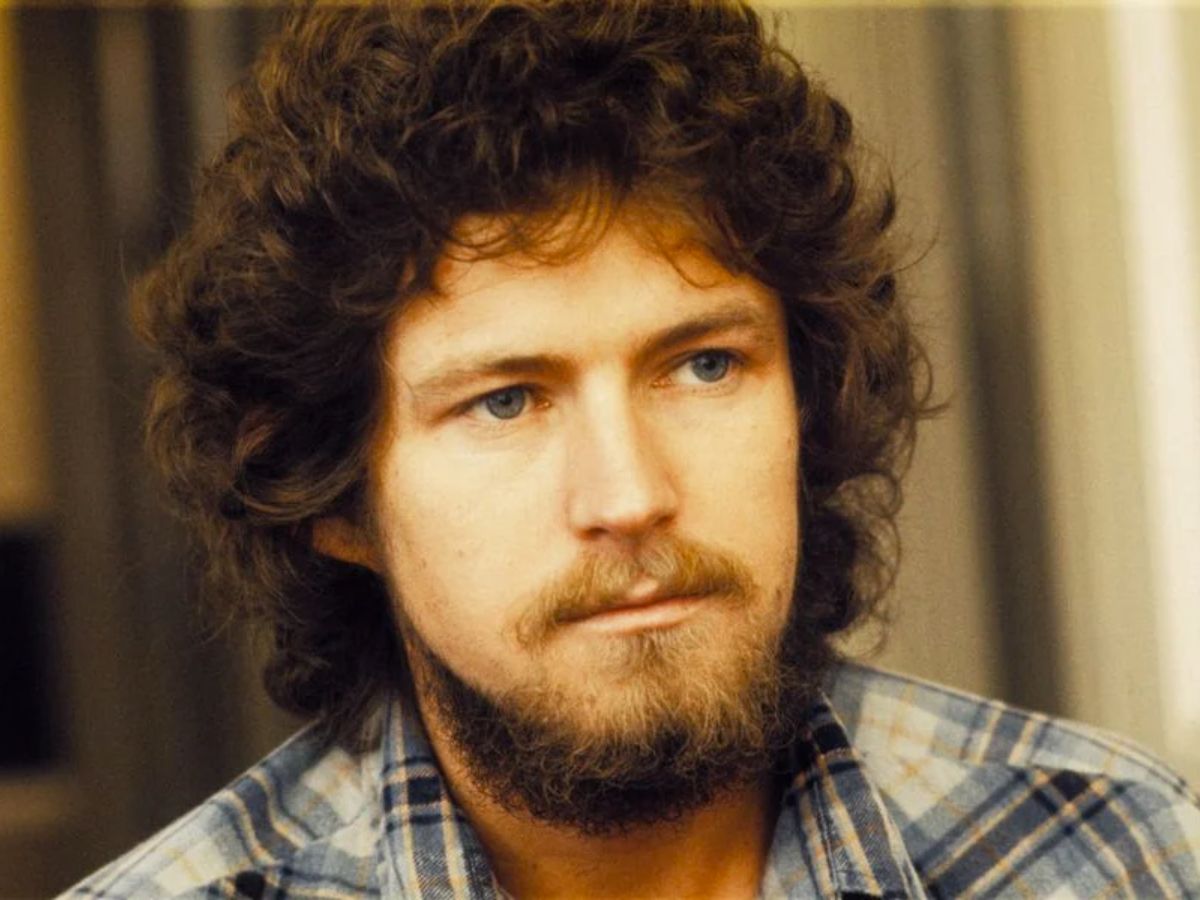

(Credit: Alamy)

Sat 23 August 2025 17:00, UK

The ending of any band is always going to lead to a handful of bruised egos along the way. Everyone usually wants out of a group for a good reason, and while Eagles were far from cordial when they decided to call it quits, Don Henley tried to keep up appearances before he seemed to get provoked in the first few years of his solo career.

For the first few months, though, it felt like the band were simply on a break. Things had become heated between Glenn Frey and Don Felder at their final show, but whereas that was one gig, most people could find ways to look past something like that if they took some time away from each other and let off steam before going back into the studio and making another record. But when Timothy B Schmitt called Frey, it was official: the dream was officially dead.

Then again, from Henley’s perspective, going solo may have been a good thing in the long run. The band were on their last legs, and there was no conceivable way for them to keep the momentum going forever, but since he sang most of the songs, he had the biggest chance of becoming a star right out of the gate. That being said, it didn’t feel like anyone had asked Henley if he wanted to be a solo artist in the first place.

He had tried his best to decompress after the dream had started to fade, but there was never any idea of him making an album immediately. He was an artist in the truest sense of the word, and if inspiration didn’t strike him at the time, it was better to wait until he had songs he could be proud of. When Frey started making his first waves as a solo artist on the album No Fun Aloud, though, Henley did get the kick in the ass he needed.

The band’s ‘Golden Throat’ understood why Frey went his own way, but that didn’t make the pain any less hurtful, saying, “I always thought in my mind that when the group broke up, we’d all get in the room together and get good and drunk and sort of cry on each other’s shoulder and say, ‘Well it was great and I love you’ [Frey] didn’t mean to do it that abrupt way, but it was too painful for him to do it any other way. I understand it now, but at the time it pissed me off. I just said to myself, ‘Well, if he’s going to make an album, I’m going to make an album too!’”

But considering how joined at the hip both of them were in the beginning, Frey and Henley could not have been more different in their solo ventures. Frey’s album was a bunch of middle-aged sounding party music half the time, and while that did have its place at the start of the 1980s, hearing Henley storm back onto the hit parade with ‘Dirty Laundry’ showed that he still had something to say.

There was nothing inherently wrong with Frey’s later hits like ‘The Heat is On’ and ‘You Belong to the City’, but looking at their solo years side by side, Henley was looking to air out a lot of his grievances. The End of the Innocence might not be the first record that a kid would buy when they walked into their local record store in the late 1980s, but anyone who followed Henley throughout his career would pick it up and realise he still had some wisdom to impart on tracks like ‘The Heart of the Matter’ or ‘New York Minute’.

So while rage might need to be kept in check in the world of rock and roll, it can also be one hell of a motivator if an artist has the right idea. And judging by how many message songs Henley would put together in his solo years like ‘The Garden of Allah’ and ‘A Month of Sundays’, he seemed to settle into his lane. He had started everything off sounding like a jilted lover half the time, but after the anger faded, he knew he needed to use his platform for the right reasons.

Related Topics