Is Britain really heading towards a 1976-style International Monetary Fund bailout? That is the warning from Jagjit Chadha, a professor of economics at the University of Cambridge who stepped down as head of the National Institute for Economic and Social Research in December.

Chadha warned that the economy was in effect on the brink of collapse. “I am reminded of what Hemingway said about bankruptcy,” he said. “First gradually and then suddenly.”

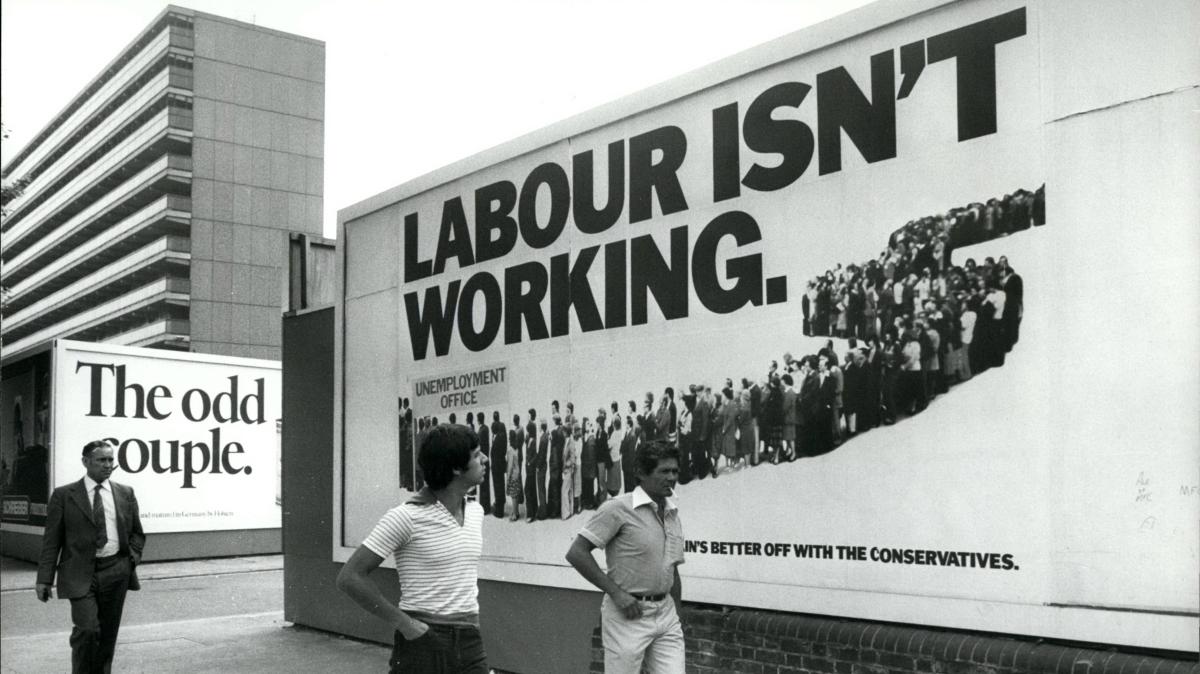

In 1976 James Callaghan’s Labour government asked for the biggest ever loan from the IMF, which Britain was instrumental in funding after the Second World War. The combination of an oil crisis and double-digit inflation made government debt deeply unattractive.

James Callaghan in 1976

PHIL FOSTER

Britain had become the “sick man of Europe” as the pound reached a record low against the dollar in June 1976. Denis Healey, the chancellor at the time, was en route to a finance ministers’ meeting in Hong Kong but turned around at Heathrow to request a bailout and prevent a complete economic collapse. Britain was given £3.2 billion under stringent conditions — higher taxes and interest rates along with the deepest cuts in government spending on record.

The economic situation is different. Inflation in 1976 was running at more than 16 per cent; today it is 3.8 per cent. But economists are increasingly concerned over the sustainability of the UK’s “twin deficits”.

First, the budget deficit the government is running, which simply means it is spending more than it is raising. In the year to last month the figure was £60 billion. Second, the current account deficit — the fact the UK imports more than it exports to the rest of the world.

Denis Healey leaving Downing Street for the House of Commons with his budget box in 1974

GETTY IMAGES

This means the UK is particularly dependent on the confidence of foreign investors, or as Mark Carney, then the Bank of England governor who is now prime minister of Canada, put it during the Brexit referendum, the “kindness” of others. There are indications that kindness may be running out.

The cost of government borrowing, particularly 30-year gilts, is steadily rising, a sign of increasing nervousness in the markets. Add to that the government’s retreat over welfare cuts and there is mounting evidence of market concerns.

“We haven’t controlled debt very well,” Chadha said. “We have regularly withdrawn from any plan to reduce expenditure, the most obvious recent example of which was the cuts to welfare.” At the same time, he said, the government had bound itself by ruling out increasing income tax, national insurance or VAT.

Britain, he said, was particularly vulnerable to an economic shock. “By failing to address this critical issue we leave ourselves vulnerable to a random shock or something from overseas,” he said. “We haven’t got a robust platform. It doesn’t mean I’m saying it will happen but we are very vulnerable to it. Unless we sound alarm bells and get some action — preferably a fiscal consolidation plan — that’s the level of seriousness we are facing.”

An IMF bailout would be a radical development, signifying that the markets have lost any faith in the UK and are refusing to lend the government money. For most of the past 40 years IMF bailouts have been largely directed at smaller developing or emerging market economies. A major exception in the past 15 years was during the eurozone’s sovereign debt crisis when the IMF was part of a troika of lenders to Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus.

Protesters outside the Greek parliament in Athens in 2010

ARIS MESSINIS/GETTY IMAGES

Paul Johnson, the former head of the Institute for Fiscal Studies who is now provost of the Queen’s College, Oxford, said he did not expect a bailout. “There clearly are issues because we are paying more interest on our debt than anyone else,” he said. “But I don’t think there’s any indication that people are going to stop lending to us. I haven’t heard anyone saying we’re at a point where we can’t access the debt markets.

“But the markets are looking less favourably on us than they are any other major economy. It’s partly because we have got one of the highest levels of debt. Obviously the government is finding it knocking on impossible to cut spending.”

Other economists believe that if there is a fresh crisis a bailout would not be enough. The Bank of England is more likely to have to slash interest rates and the government would carry out an emergency austerity budget to restore market confidence.

But some investors are increasingly concerned about the autumn budget. Rachel Reeves will have to fill a deficit of as much as £40 billion in the public finances and there are concerns that without spending cuts there could be another bond and currency market panic.

Mark Dowding, the chief investment officer at RBC BlueBay Asset Management, said the pound was vulnerable to another “Truss tantrum” if Reeves cannot bring down “runaway welfare spending”.

“There is a sense that the market’s trust in the government’s policy stance is starting to evaporate,” he said.