This is a great time to be addicted to AI! Everywhere you look, we’re spoiled for choice – especially of LLMs (large language models) such as Claude, Gemini, ChatGPT. At the last count , there were at least 44 LLMs publicly available (and doubtless countless others under corporate wraps).

And most of them appear to be free to use; unless you happen to be accessing them via an application programming interface, or API (in which case you’ll be paying a fee). Which is odd when you come to think of it, given that LLMs are computationally expensive to run – and to create. Asking ChatGPT for “reliable guides to the history of the Crimean war”, for example, requires significantly more computation – and therefore energy – than putting the same query to Google.

At the moment, the predominant business model used by AI companies is the “freemium” one: basic use is free, but if you want bells and whistles, you’ll have to fork out. This works for some (including a number of my colleagues, who are paying $200 a month to OpenAI and its ilk), but it’s of no interest at all to the average punter who has always believed that – as the ancient netizen saying went – “information wants to be free” and, accordingly, is currently enjoying the superabundance of “free” AI.

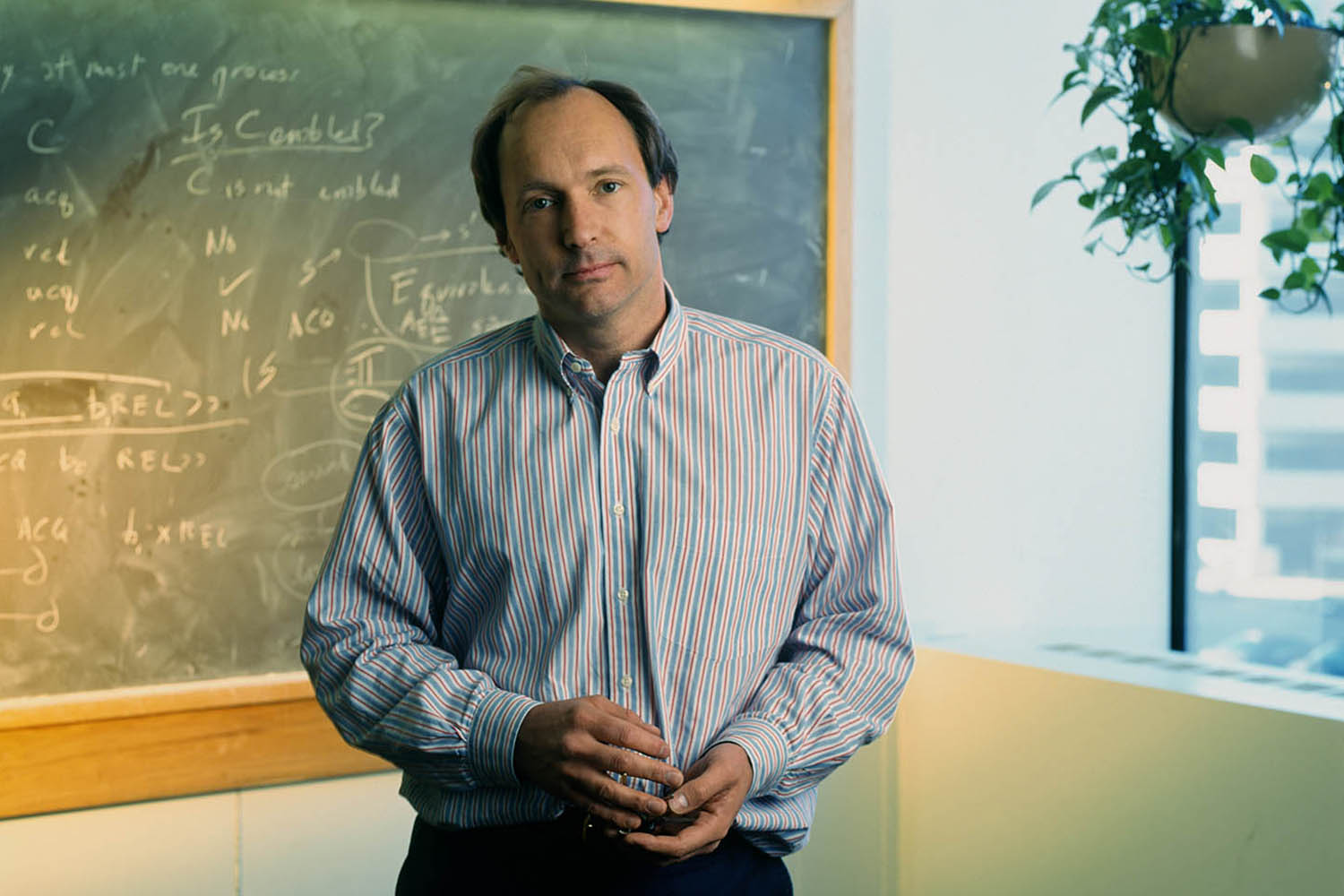

Which raises an interesting question: since there’s no such thing as a free lunch, what’s going on? And where is it heading? As it happens, we know the answer to that last question, because we’ve seen this movie before. Its opening scene was shot in the early days of the web, when people were trying to build businesses on top of the platform created – and generously donated to the world – by Tim Berners-Lee (whom God preserve).

The more entrepreneurial geeks of the time (the late-1990s onwards) realised that the key to building a successful platform was to “get big fast”, ensuring that your platform became so large that network effects would kick in before competitors got their act together. And since the quickest way to get big fast was to provide free services, that’s what Facebook, Google et al did.

The current AI arms race between tech giants looks awfully like a death march in search of supremacy

But they also cunningly designed their platforms to make it as difficult as possible for users to leave. With social media, that turned out to be a very powerful disincentive: leavers wouldn’t be able to take their “social graph” – their network of friends – with them. Users feared the resulting Fomo, which, coincidentally, is still one of the reasons people find it so hard to come off X. Network effects can be tyrannical when push comes to shove. Network effects can be tyrannical when push comes to shove online.

As we swan around in this new, idyllic non-marketplace where Claude, ChatGPT, Gemini, Perplexity, DeepSeek, Llama and more flaunt their free credentials and formidable capabilities, two awkward questions come to mind. How long will this phase – which is clearly unsustainable – last? And how will the AI industry evolve after the bubble has burst?

Here’s where the history of the last three decades may again be helpful. The current AI arms race between tech giants looks awfully like a death march in search of supremacy. The goal is to get biggest fastest and to create “one LLM to rule them all”; a system that does to its competitors what Facebook did to MySpace or, in an earlier age, Microsoft did to Netscape.

Whatever happens, though, it looks as if LLMs may eventually eclipse not only search engines but social media platforms; and, again, the history of the web can provide some insight into what’s likely to happen when and if that seismic transformation happens.

In the 1990s, the web was exciting but chaotic until Google arrived and the world changed overnight. But the company lacked a business model until its founders realised that monitoring their users’ clickstreams could provide an information flow that could be fabulously monetised. Thus was born what came to be called “surveillance capitalism” , which became – and remains – the web’s dominant business model.

One of the great surprises of Google’s monitoring was how much clickstreams can tell you about people. But we know already that people’s interactions with LLMs can be much more revealing, more intimate and surprising than their clickstreams. Just after I wrote that sentence, a New York Times article popped into my inbox. The title: “What my daughter told ChatGPT before she took her life.”

So if AI corporations start surveilling their users’ interactions with LLMs – as they eventually will, just as social media companies did – they will have inadvertently discovered a new, and even more pernicious, business model. Let’s call it “thoughtstream capitalism”.

Photograph by Karjean Levine/Getty