This article is part of our 75 Years of Speed series, an inside look at the backstories of the clubs, drivers, and people fueling the sport.

Can women race in Formula One?

The short answer is yes, they can. There are no regulations that prohibit anyone from competing based on sex or gender. But the bigger question is: why are there no women racing in F1 today? And that answer is more complicated.

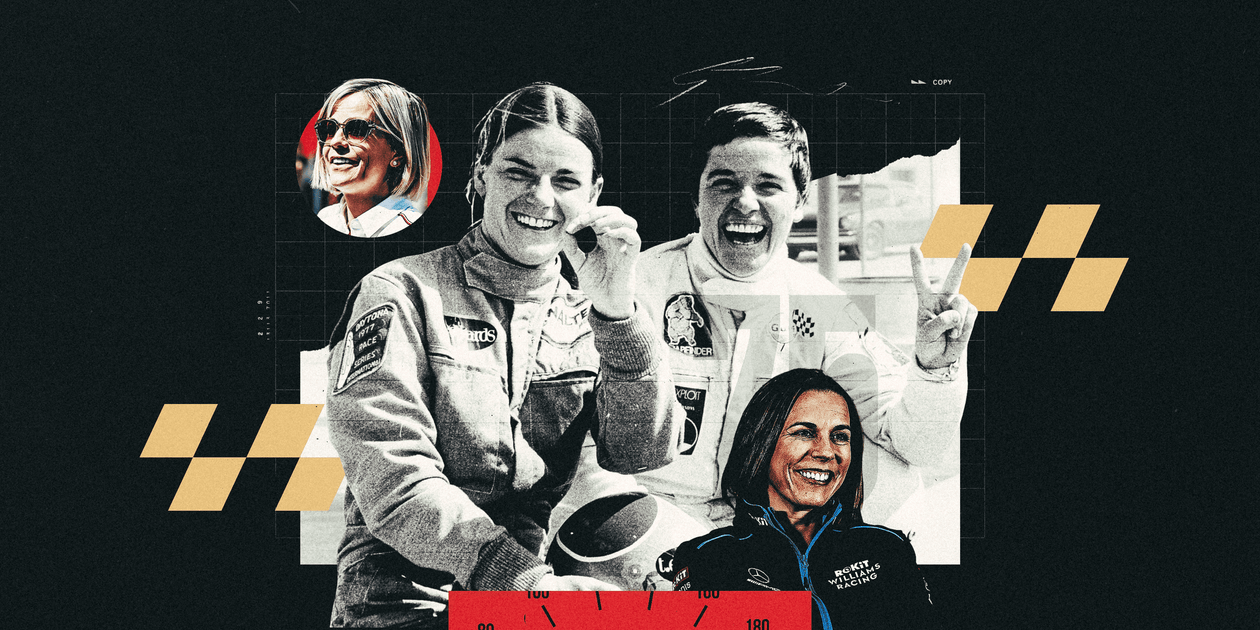

Since the start of the world championship in 1950, five women have entered an F1 race: Maria Teresa de Filippis, Lella Lombardi, Divina Galica, Desiré Wilson and Giovanna Amati. Only two have qualified and started a grand prix (de Filippis and Lombardi). Lombardi remains the only woman to score in the world championship standings, with half a point for finishing sixth in the 1975 Spanish Grand Prix.

The last time a woman entered an F1 race was in 1992, when Amati failed to qualify for three races, and Damon Hill replaced the Italian driver at the Brabham team.

A number of women have driven F1 cars and filled test and development driver roles since then, such as Katherine Legge testing with Minardi in 2005, Williams signing Susie Wolff (who is now the managing director of the F1 Academy championship) for these dual purposes in 2012, and Sauber bringing on Tatiana Calderon as a development driver in 2017.

Wolff is the last woman to participate in an F1 practice session, having taken part in outings for Williams at Barcelona and Silverstone in 2015. But, a decade later, a woman hasn’t come close to driving an F1 car on a race weekend. Aston Martin’s Jessica Hawkins is the most recent woman to test the latest-generation F1 car in 2023, but no female drivers are competing in Formula Two or Formula Three this season.

And while there are more women present in STEM roles, such as Hannah Schmitz being a principal strategy engineer at Red Bull or Haas’ Laura Mueller becoming the first female race engineer this season, there have only been two female team principals in all of F1’s world championship history, the last being Claire Williams, who stepped down as Williams’ deputy team principal in 2020.

So, how did we arrive at this point, and what challenges still need to be addressed? The Athletic spoke to several women in motorsport to gain a deeper understanding of the landscape and identify the questions that remain.

“I think the main reason that we don’t have a female in Formula One is because so many drivers start at a young age, and you need to have so many pieces of the puzzle to make it to Formula One. If you’re missing one of those pieces, you won’t make it,” Hawkins said to The Athletic. “There are fewer opportunities for a female to have every piece of that puzzle. So if we can introduce more at a younger age, make it more visible that women are allowed in Formula One, I think we stand a better chance.”

A brief history of women in motorsport

Auto racing’s roots can be traced back to the late 19th century, with one of the first organized competition races taking place in 1894 in France. Women’s involvement in the sport dates back to those early years of motorsport’s history, although their presence was often limited due to the societal norms of the era.

Hélène van Zuylen is considered one of the first women to compete in an international motorsports event. She entered the Paris-Amsterdam-Paris Trail in 1889, but had to compete under a pseudonym due to societal expectations and her family’s prominence (she was a member of the influential Rothschild banking family).

And then there’s Camille du Gast, a Frenchwoman who was also an animal rights activist and feminist. She competed in the 1901 Paris-Berlin race and became “the first and only woman official for the Automobile Club de France” in 1904, according to the Library of Congress.

Duchess of Uzès, Anne de Rouchechouart de Mortemart, who founded the Automobile Club Féminin de France in 1926, rounded out the trio of female French drivers who paved the way into motorsports during the Belle Époque era, which spanned up to the outbreak of the First World War.

Lella Lombardi looking at her Formula 1 car before racing at Brands Hatch in 1975. (Ben Martin / Getty Images)

While these women were proving that they belonged in this male-dominated space, they still had to fight for entry, as seen by their defying of societal norms and use of pseudonyms. And the movement wasn’t just happening in France. During the same era over in the United Kingdom, Dorothy Levitt became the first British female racing driver and is said to have taught Queen Alexandra and the Royal Princesses how to drive. A few decades later, American Louise Smith emerged as the “first lady of stock car racing.” She won 38 Modified races during her 11-year career.

As far as grand prix racing, one of the early notable stars was Hellé Nice, a French model and dancer turned racer. She tried to enter a race at Brooklands in 1921, but according to the BBC, her entry was denied because she was a woman. A skiing injury ended her dancing career, though, and her focus turned fully to motorsports. The first Women’s Grand Prix was held in France in 1929, and she won the race. The French newspaper L’Intransigeant wrote, “The driving was magnificent: nobody who saw it would feel able to argue that women drive less well than men.” And the Bugatti marque later asked for Nice to be its driver. Because of her racing success, she became known as the Bugatti Queen.

Nice was the only woman racing on a grand prix circuit for multiple seasons, but this was before the F1 world championship was created in 1950. Women’s involvement in motorsports increased in the years following the Second World War. De Filippis and Lombardi are the most notable women who have reached F1, and both competed in races. But it’s been 50 years since a woman has competed at the pinnacle of motorsport. And after Amati’s brief stint in 1992, it was two decades before a few women rose to high-level, front-facing positions on the grid.

Sauber named Monisha Kaltenborn its team principal in 2012, the same year that Williams brought Wolff onto the team as a development driver. A year later, the Grove-based team, still owned by her family, named Claire Williams as deputy team principal at 36. This made her the second woman holding the position of an active team boss on the F1 grid.

In the early 2010s, F1 was still male-dominated. People still expressed skepticism, as seen in a 2014 comment by former F1 CEO Bernie Ecclestone, who asked, “Susie Wolff is good, but will she ever be in a position to show how good she is?” and added, “I doubt it.” Wolff was still a development driver for Williams at the time and few women were breaking through to the top levels. It’s key to remember that the #MeToo movement didn’t start gaining public momentum until 2017, marking the beginning of further progress within society.

Wolff made her F1 FP1 debut at Silverstone in 2014 and was the first woman to participate in an F1 session since Amati 22 years prior. Wolff then had a second practice outing in Germany later the same season and was two-tenths of a second off 11-time grand prix winner Felipe Massa’s lap time.

“When I was in Formula One, it was very different in 2014,” Wolff told The Athletic. “I was the only one, and there was a lot more skepticism. There was a lot more stigma around being a female driver.”

And as far as the female team principals, Williams said there were challenges, as she was the only woman leading an F1 team for most of her tenure. Sauber parted ways with Kaltenborn in 2017, and Williams held her role until her family sold its eponymous organization. Looking back on her tenure, in addition to the on-track results the team achieved during that period, Williams said she was proud of “the work that I did around diversity and inclusion, and promoting women in our organization and transforming the workplace to support our female members of the team, but also hopefully creating a better pathway for other women to come into the sport.”

Over the years, progress has been made in various areas; however, women remain underrepresented in F1. Some face similar issues that have plagued the space (and society) for years. Societal stereotypes and cultural barriers persist, and there’s a lack of role models, which F1 Academy is addressing by creating role models among its drivers as they race on the F1 support bill. It’s an aspect of the conversation Williams addressed during her time as a deputy team principal.

Williams made her start in the motorsports world as a communications officer for Silverstone Circuit in 2000 and then joined Williams Racing’s communications team two years later. She recalls that when she began working in the F1 world, “the women that worked in the sport worked in PR, marketing, hospitality. So few women, if any, worked on the engineering side — the aerodynamic side, on the race team, mechanics, etc. (It) just didn’t happen.”

Williams continued, “It’s not what women kind of did. It’s not what women thought about doing. And even when I took over running the team, I think we only had one woman in our aero department. And as a consequence of some of the challenges that I faced being a woman running a Formula One team, I wanted to try to drive some change in my team.”

When she took over, running Williams on behalf of her father, Frank Williams, only nine percent of the entire workforce identified as female, Williams told The Athletic. By 2020, when she left, that number had risen to 19 percent. This statistic ranged across different disciplines, including more women working in the aero and design departments. She said, “That was through proactive work — from leadership, living and breathing diversity every day, and promoting women.”

The current state of women in motorsports

It’s been a decade since Wolff’s last FP1 drive, and since then, the closest women have come to F1 is F3 (Sophia Floersch, in 2020 and 2023-2024) and testing a modern-era car (Hawkins, with Aston). But changes have been made to the pipeline, which has become more male-oriented over time, and there’s still more work to do.

The W Series, an all-female single-seater racing series, began in 2019, with the primary goal of providing opportunities for female drivers. However, it only lasted for three seasons (2019, 2021, and 2022, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic) before it ended due to financial issues. The final races of the 2022 season were cancelled, and the championship entered administration the following year. Another all-female racing series began in 2023, though this was heavily backed by the F1 organization, F1 Academy.

What made this one different, though, is that it’s part of F1’s pyramid and is at the Formula Four level, using an equivalent car with some design adjustments to resemble an F1 challenger. All 10 F1 teams support a driver, and its calendar is aligned with F1’s own, such as how this year’s season finale will be held at the Las Vegas Grand Prix.

Giovanna Amati is the most recent woman to race in F1, in 1992. (Paul-Henri Cahier / Getty Images)

“It’s nice to see the support around F1 Academy from the Formula One teams as well,” Hawkins said. She previously competed in the W Series and now races in the GT World Challenge Europe Endurance Cup for Comtoyou Racing, while serving as Aston’s Head of F1 Academy. “I think it’s needed, and I think that it’s also speaking volumes for how seriously everybody’s taking it, which is a far cry from what it was when I first started. There was nothing like this. It simply wouldn’t have happened.”

It’s not that a single significant change is needed to help more women enter F1, but rather changes throughout the entire pipeline, from grassroots karting to the top level of single-seater motorsport. And it’s something that won’t happen overnight. As Lauren Forrow, the head of driver development for the More Than Equal organization, said, “If the male system worked for females, then a female would have already made it. But it doesn’t. It does need to be different.”

Several main factors combine to hinder progress. Motorsport is incredibly expensive, with costs increasing as drivers progress through the various levels. It ranges from paying for equipment and gear to securing the right amount of track time and travel, among other expenses. Ahead of the 2024 season, F1 Academy reduced the driver contribution from €150,000 to €100,000, in a bid to make the junior single-seater category accessible.

The cost of pursuing a career in motorsport applies to everyone, not just women, and many drivers look toward sponsorships to help fund their careers. However, some sponsors may be hesitant to invest in women in motorsport, possibly due to the lack of female examples at the higher levels of the sport. There is a proof of concept with men, but with women, fewer have broken that glass ceiling.

“I think women are viewed as more risky, and people do talk about it in terms of a return on investment,” Forrow said. “And what I guess my experience from other sports would tell me is you can identify at least talent. It isn’t just access to practice, and I suppose that’s where motorsport is quite unique in that you could be slightly less talented and have a little bit more money and do quite well, versus being incredibly talented in other sports, but maybe you’re weaned out of that kind of system by age.”

The financial challenge creates a domino effect, impacting track time, access to competitive equipment, and proper training. It has the potential to hinder the development of a driver, regardless of gender or sex. But considering the cost as drivers progress up the ladder, it becomes less accessible and harder to advance careers without the financial backing, regardless of talent level.

Chloe Chambers looks on ahead of an F1 Academy race in 2025. (Meg Oliphant / Getty Images)

More Than Equal’s research also found that female drivers’ careers typically last between one to five years and have a later start than their male counterparts. Forrow said that women are, on average, “two years behind, either by start or opportunity.” There is also the physical element, which is influenced by stereotypes, and further research is needed. Forrow said, “We know with young athletes that you need to give time for the body to develop, for them to go through physical maturation and to be able to really understand what somebody’s headroom is.”

More Than Equal has partnered with Manchester Metropolitan University’s Institute of Sport, and two critical pieces of research are being carried out by two PhD students — “one focusing on female driver health and performance and another seeking to build a psychological, cognitive, and physiological profile of drivers at different stages of development,” according to the announcement of the project.

These are two under-researched topics in the motorsport space. Take the menstrual cycle, for example. Different aspects of it have an impact on how one trains and performs, such as the individual’s higher core temperature during the cycle or its effects on fueling and recovery, Forrow said. That this basic research into how to prepare women physically for full-time racing is only now being considered underscores how motorsports was designed without women in mind — a still evident reality from the era when women, such as Van Zuylen, had to use pseudonyms just to enter races.

Questions still remain for the future, such as how these changes can become the norm. The general feeling within the motorsport world is that the tides are changing. Stereotypes and misconceptions do still exist, such as people thinking women aren’t allowed to race, as Wolff mentioned, but there are some programs, such as F1 Academy and More Than Equal, that are working towards changing the system.

Women are still underrepresented, but a collaborative approach is needed to undertake this massive, complex challenge. As Forrow put it, “It is a system responsibility.”

“Naturally, we know that a woman hasn’t reached the very top in the last 50 years because the system hasn’t been built for them,” Forrow said. “So all of these programs coming together to create systemic change will help to combat that. It’s not a kind of magic pill.

“There’s not a ‘one size fits all’ for all of the problems, but there is absolutely a collective movement towards wanting to understand the differences in the female space and what it would take for a female driver to thrive and be successful in Formula One.”

The 75 Years of Speed series is part of a partnership with Shell. The Athletic maintains full editorial independence. Partners have no control over or input into the reporting or editing process and do not review stories before publication.

(Top photos: Artur Widak, ISC Archives, Bryn Lennon / Getty Images; design: Will Tullos)