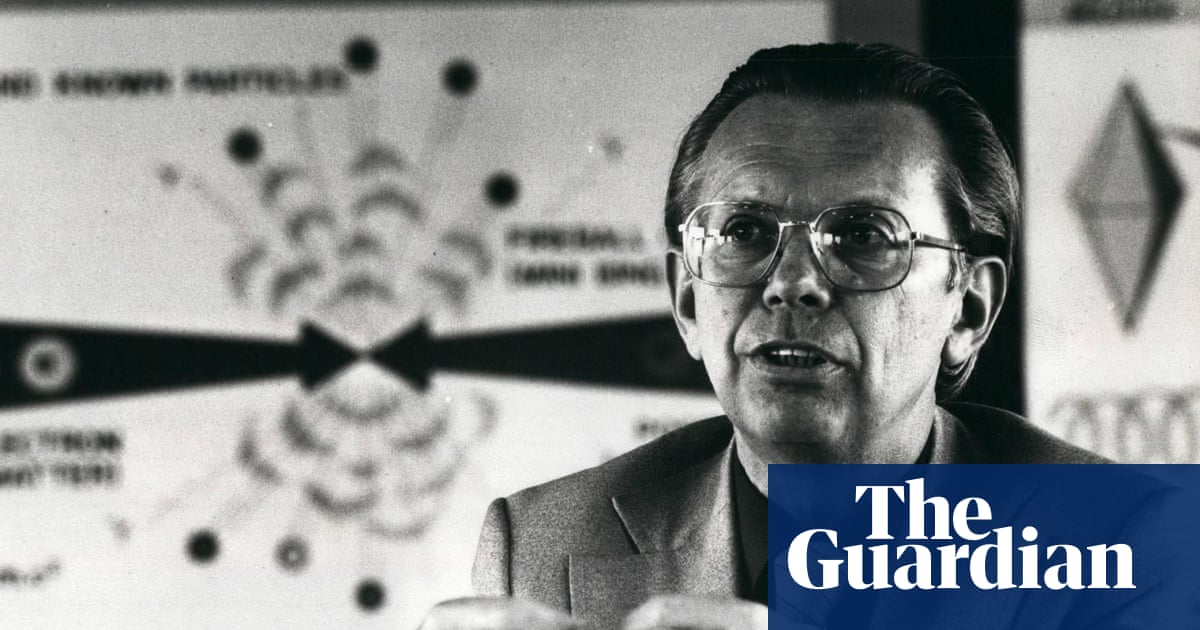

The German physicist Herwig Schopper, who has died aged 101, was director general of Cern, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research, from 1981 to 1988, overseeing the laboratory’s first Nobel prize-winning discovery and paving the way to another. It was thanks to Herwig’s tenacity that the laboratory laid the foundations – literally – for what would become the Large Hadron Collider.

On his retirement in 1989, Herwig embarked on a second career, applying his experience of international science to the field of diplomacy. Working closely with Unesco, he played a key role in establishing the Sesame laboratory in Jordan: a new Cern to sow seeds of peace in a troubled region.

Herwig was chosen to lead Cern in 1980, and took office as the laboratory was embarking on ambitious new projects. Carlo Rubbia had persuaded Cern to convert its largest accelerator into a collider. Instead of accelerating particles and smashing them into a stationary target, it would collide beams head-on, giving scientists a much greater potential for discovery. In 1983 a major discovery was duly announced, leading to a headline in the New York Times that read “Europe 3, US not even Z-zero”: the long-awaited discovery had been of three new particles named W+, W- and Z0. Rubbia, along with Simon van der Meer, received the call to Stockholm the following year.

However, Herwig’s greatest legacy at Cern is probably his tenacity in insisting that the tunnel for Cern’s next accelerator, called LEP (the Large Electron-Positron Collider), should be 27km long and not 22. The longer option would require more difficult civil engineering, but would allow a hadron collider to be installed once LEP’s job was done. Without this decision, the Large Hadron Collider would not have seen the light of day.

Herwig was born in Czechoslovakia, which had recently emerged from the Austro-Hungarian empire, in the German-speaking town of Landskron (today Lanškroun in the Czech Republic), and enjoyed an idyllic childhood. Although his parents, Franz Schopper, a teacher, and Margarethe (nee Stark), split amicably when he was young, both provided a nurturing environment.

Through his maternal grandparents, who ran a hotel on the Adriatic coast of what is now Croatia, Herwig developed a love for physics. Two professors, from Belgrade and Budapest, were regular visitors, and on his summer holidays, Herwig would tune in to their conversations about the physics of the waves that lapped the beach. From his father’s second wife, Friederike (Culik), he learned a love of music.

Schopper with the physicist Chien-Shiung Wu. Photograph: Cern

In 1938, the idyll was broken. When the Sudetenland was annexed after the Munich agreement, Herwig became a German citizen. Graduating from high school in 1942, he had no choice but to enlist, joining the signals corps on the basis that he might learn some physics along the way. Deployed to the eastern front, he also signed up for correspondence courses at Prague’s Technical University.

Finding himself in Berlin at the end of the war, Herwig was relieved to be sent west into the hands of the western allies rather than towards the Soviets. After serving as a translator for the British Military Administration, Herwig enrolled at the University of Hamburg, where he studied optics. He rapidly established a reputation as a good scientist and a skilful manager. When his teacher was offered a chair at the university in Erlangen, Herwig followed, but it was not long before he was offered chairs himself: first at Mainz, and then at Karlsruhe.

Through a range of sabbaticals, Herwig learned from other pioneers of particle physics. The first of these was Lise Meitner in Stockholm in 1951, shortly after his marriage to Ingeborg Steiler, in 1949.

During a year at Cambridge, working under Meitner’s nephew, Otto Frisch, Herwig conducted an experiment that confirmed a recent prediction about the fundamental concept of symmetry in physics. The theorists, Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang, received a Nobel prize for their efforts, but the experimentalists went empty handed, ostensibly because the prize can be split only three ways. A team led by Chien-Shiung Wu had published before Herwig. Although missing out on the prize, the experience led to a long friendship between Herwig and Wu, the first lady of physics.

A third sabbatical, with Bob Wilson at Cornell in upstate New York in 1960, provided Herwig with his first experience of circular particle accelerators: essential training for his subsequent jobs as director of Germany’s national laboratory for particle physics, Desy (Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron), where he welcomed the first Chinese physicists to travel west after Mao’s cultural revolution, and then Cern.

A worker at the Large Hadron Collider tunnel during maintenance work. Photograph: Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images

When he reached his 65th birthday in 1989, he embarked on a second career as a scientific diplomat, working largely with Unesco, which had steered Cern into existence in the 1940s and 50s. The idea for Sesame had been hatched years before, but as it matured, the project required a leader who could rise above the tensions of the region. In 1997, Herwig took on the challenge of steering the fledgling organisation into existence.

He rewrote the Cern convention as a governing document for Sesame, and he presided over the selection of a site for the new laboratory, north of Amman in Jordan. He corralled potential members, including Israel, Iran and the Palestinian Authority, into a coherent group, and when he handed over the reins of the Sesame council to Chris Llewellyn-Smith, another former Cern director general, in 2008, the new laboratory existed as a legal entity and a physical building.

In 2017, Llewellyn-Smith presided over an opening ceremony and today, despite chaos all around, Sesame is a world-class laboratory, providing a beacon of peaceful collaboration in a deeply troubled region. Herwig had shown the value of leading by example, working from the bottom up, and understanding every aspect of the complex fields he worked in.

He and Ingeborg had two children, Doris and Andreas; she died in 2009. Herwig is survived by his partner, Ingrid Krähe, his children and three grandchildren.

Herwig Schopper, scientist and diplomat, born 1 February 1924; died 19 August 2025