After watching Yorgos Lanthimos’s Bugonia and Gus Van Sant’s Dead Man’s Wire within the span of a couple of days, it’s hard not to feel like there’s something in the air. Both films depict downtrodden men kidnapping wealthy executives, even though they have wildly different provenances: Bugonia is based on a 22-year-old Korean sci-fi thriller, and Dead Man’s Wire is based on a real-life event that occurred in Indianapolis in 1977. To these two we can probably add Romain Gavras’s Sacrifice, which I haven’t seen yet, about a group of activists taking a group of wealthy people hostage; that one will premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival in a week or so. And who knows what other upcoming movies will ponder similar scenarios. (There are, one assumes, several Luigi Mangione biopics in the works.) Van Sant’s take, his first feature in seven years (though he also did direct much of FX’s Feud: Capote and the Swans), is premiering out of competition at the Venice Film Festival. It has plenty of gritty ’70s atmosphere (facial hair! Radio DJs!) and feels grounded in its time and place, but it also has a purposeful whiff of timeliness that tells us it’s as much about today as it is about 1977.

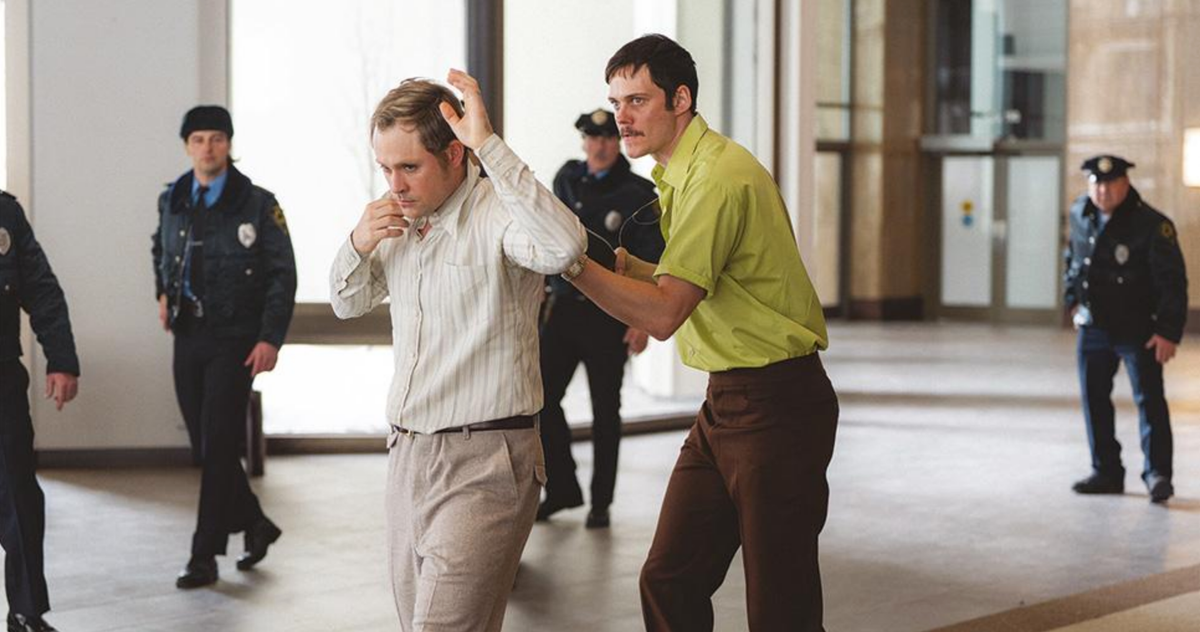

Dead Man’s Wire sticks generally to the facts in its portrayal of Tony Kiritsis (Bill Skarsgård), an aspiring businessman who one day in February 1977 walked into the offices of Meridian Mortgage and kidnapped his broker, Dick Hall (Dacre Montgomery), wrapping a wire attached to a shotgun around the man’s neck. In front of policemen and news cameras, Tony walked Dick to his car and then drove with him, the cops following quietly behind, back to his apartment, where he continued to hold him captive for several days. Tony’s demands were $5 million, immunity, and an apology from Meridian. He claimed that the mortgage company screwed him over after he took loans to develop a once-neglected piece of real estate where he intended to build a shopping center. Tony cleared the area himself and negotiated with prospective retail businesses, but he says that once his brokers saw the site’s true potential, they diverted him to a less lucrative spot, and he had to default on loan payments.

Tony’s grievances are significant, and Dead Man’s Wire repeats them several times, because they make it clear that this man, while certainly something of an under-socialized kook, wasn’t some wild-eyed anarchist or an overexcited revolutionary. No, he was an honest-to-goodness capitalist, someone who believed in the profit motive and the idea that hard work and ingenuity would ultimately pay off. When he’s asked at one point if he has any kids, Tony replies, “My businesses are my children,” the way a successful CEO might in a Forbes interview. He apologizes to the cops he’s inconveniencing, saying he knows some of them and believes they’re good men.

It’s a purposeful misreading of history to assume that the people who ultimately wind up lashing out against the system are dedicated opponents of that system. America’s all-purpose bogeyman might be the bomb-throwing rebel, but in truth, disillusionment inspires more violence than ideology. Tony has fully bought into the dream, and Skarsgård plays him with excitable, boyish humor, almost as if the whole thing were a game. He seems convinced that once this whole thing is over everything can get back to the way it used to be; he’s just a child, momentarily rebelling against the world that made him. (It’s hard to believe this actor was playing Nosferatu less than a year ago.)

Something similar occurs with Dick, who seems pretty powerless himself. He’s an executive in a business run by his father (Al Pacino), who happens to be on vacation when Tony initiates his plan, which is why Dick winds up as the captive. Reached by phone, the father comes off as a cold, uncaring man, and Pacino portrays him with chilling aloofness. “I’m sorry he missed his payments,” is the only apology dad is willing to give to Tony, which probably shocks his son more than it shocks anyone else. Dick is also a child of a system that doesn’t love him back, only in this case it’s his literal family. Both he and Tony have been sacrificed to the almighty dollar.

Dead Man’s Wire is exciting whenever it focuses on these two men, who’ve been brought uncomfortably close by circumstance. It’s less successful when it tries to expand beyond Tony and Dick, to the journalists and cops and other officials who’ve gotten sucked into this case. A subplot about a local TV news reporter (Myha’la) who sees an opportunity to cover a prime piece of breaking news and fights to continue her reporting even as the big shots want to take over feels pertinent at first, but ultimately gets lost in the shuffle. Meanwhile, a popular radio-station DJ, Fred Temple (Colman Domingo), gets roped into the madness because Tony admires and trusts him. That did actually happen, but Van Sant and screenwriter Austin Kolodny make some additional stabs at turning Fred into the spine of the picture, structuring the movie around his broadcasts — a filmmaking convention that doesn’t really bring anything new to this particular story. What works in Dead Man’s Wire is its stylistic claustrophobia and its prevailing mood of disillusionment. It doesn’t need to expand its scope: It’s already got a powerful civilizational metaphor in its central image of two broken capitalists locked in a murderous standoff.

Sign up for The Critics

A weekly dispatch on the cultural discourse, for subscribers only.

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice