A group of anthropologists and geneticists have been exploring the population distribution and the structure of the Denisovan MUC19 gene variant in people.

The variant was originally detected in DNA from bone fossils of humanlike Denisovans, who vanished from the Earth tens of thousands of years ago. Their fossils have been discovered in a Siberian cave and sites in Asia.

The MUC19 gene codes for a gel-like substance in saliva and mucus. It is thought to have a role in the body’s protective defenses against infections. It is unclear how these functions differ in people with the Denisovan variant of this gene.

This intriguing gene variant was among those passed down from Denisovans to another now-extinct, humanlike species, the Neanderthals. Interbreeding then transmitted the Denisovan MUC19 gene in Neanderthals into prehistoric ancestors of modern human beings.

Most people, except for those entirely of African descent, have small percentages of Neanderthal and Denisovan genes in their genomes.

Scientists recently discovered that the Denisovan MUC19 variant occurs with greater frequency among people who have regions of their genome inherited from ancient Indigenous Americans. For example, 1 in 3 people of Mexican ancestry are likely to have a copy. In contrast, only 1 in 100 people of Asian ancestry are estimated to have the variant.

The research findings and an analysis of their possible implications were reported Aug. 21 in Science.

Between 15,000 and 20,000 years ago, according to one widely accepted theory on the peopling of the Americas, some early humans migrated from the Asian continent into North America when a Bering Land Bridge formed between what is now Siberia and Alaska.

The researchers on the recent project wondered if those prehistoric humans with the Denisovan MUC19 variant could better withstand aspects of inhospitable living conditions they encountered in the Americas. Some possibilities include exposure to different pathogens, new allergens and unfamiliar food sources.

Whatever selective forces existed meant that having the Denisovan MUC19 variant benefited early humans and their progeny in the Americas. That would have made it more likely to be passed on to descendants of the ancient Indigenous Americans.

Previous studies by senior author Emilia Huerta-Sánchez at Brown University have suggested that Denisovan genes present in human genomes could have promoted distinct adaptations to different environments, such as living at high altitude in Tibet.

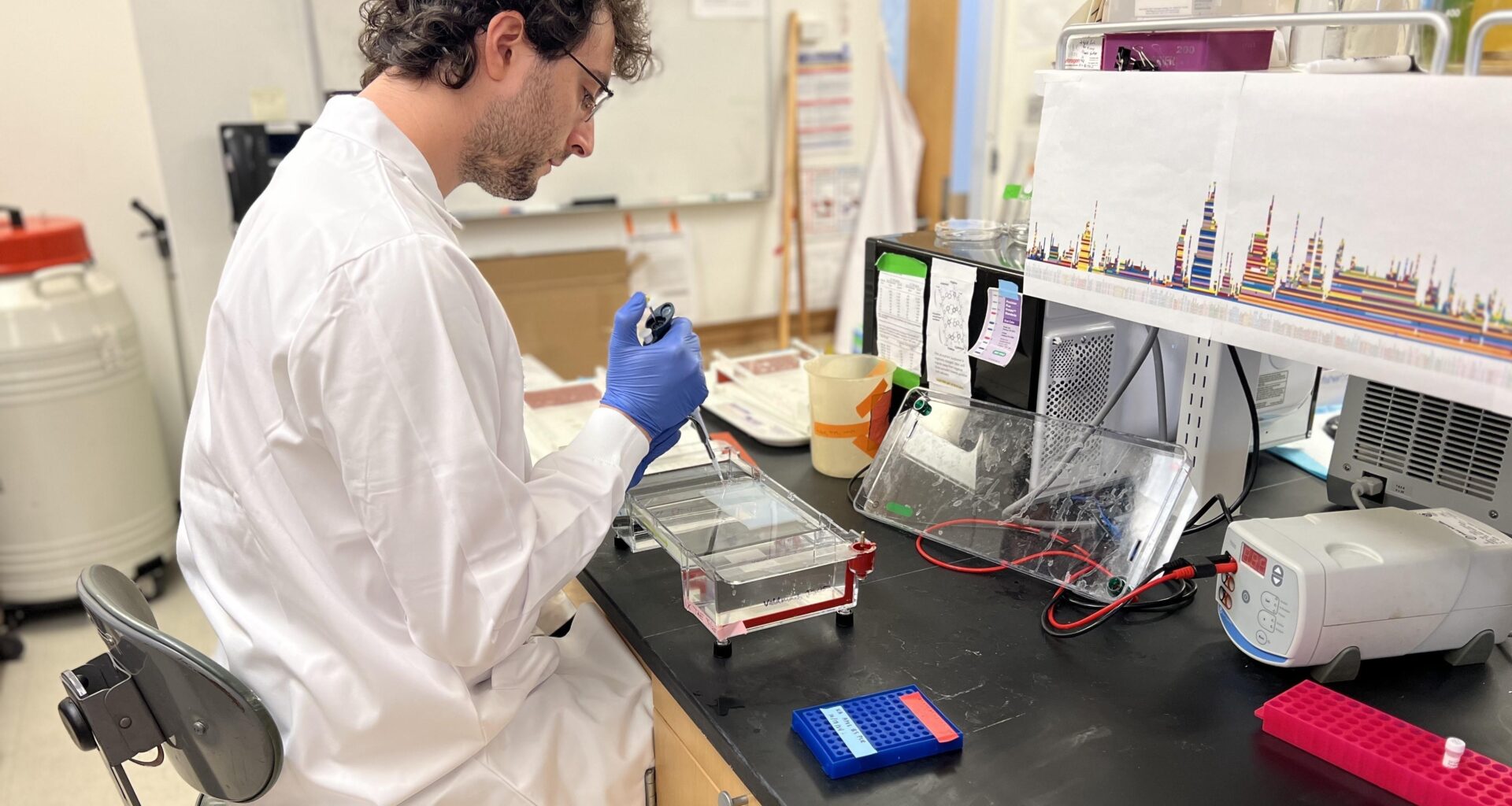

“Our contribution to the project was to identify a tandem repeat expansion that occurred on the MUC19 variant,” said Paul N. Valdmanis, associate professor of medicine, Division of Medical Genetics, at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

A tandem repeat is an area of a genome containing multiple adjacent copies of the same DNA sequence.

The tandem repeat expansion the Valdmanis lab detected had increased the length of a coding exon of the Denisovan MUC19 gene by more than 12,000 nucleotides. A coding exon is a segment of DNA that contains information for producing proteins.

“This expansion more than doubled the length of the coding exon,” Valdmanis said. “This expansion likely provides a functional explanation for the increased frequency of the Denisovan variant in Indigenous Americans.” The expansion of a coding exon can affect a gene’s activity in several ways, such as altering the properties of the protein produced.

“Most tandem repeat expansions identified to date cause devastating neurodegenerative disorders like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or Huntington’s disease,” Valdmanis added. “This is one of the first examples of a repeat expansion that confers a beneficial effect in humans.”

The changes in this gene’s activity resulting from its expansion, along with additional details about its evolutionary history, have yet to be determined. Such future research might help explain the specific mechanisms by which this Denisovan variant provided a selective advantage in ancient Indigenous Americans.

The lead authors of this project were Fernando A. Villanea of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Colorado and David Peede of the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Organismal Biology at Brown.

The project was funded by The Leakey Foundation, National Institutes of Health (1R35GM128946-01, R35GM142978, R01NS122766), Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Blavatnik Family Graduate Fellowship in Biology and Medicine, Brown University Predoctoral Training Program in Biological Data Science (NIH T32 GM128596), Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award at the Scientific Interface and the Human Frontier Science Program.