Keeping a training log is one of the most powerful tools for improving cycling performance — not just for recording miles and watts, but for analyzing what truly leads to success. A recent study (Roete et al. 2025) examined the training diaries of professional women cyclists across multiple seasons to uncover patterns that separated highly successful campaigns from less successful ones. The findings highlight how training quantity, intensity distribution, and smarter race execution can make the difference between breakthrough results and frustration — and offer lessons that every cyclist can apply.

One of the best reasons for keeping a training log is analyzing it to figure out what worked and what didn’t work. Can we see what characteristics highlighted highly successful versus less successful seasons?

There are lots of options available for tracking your training. The most basic is a simple paper notebook, and a dozen years ago I found binders full of my paper training logs from my early racing days in the 1980s while helping my parents move houses.

Nowadays, there are a plethora of high-tech computers and software to track every second of every workout on and off the bike. They will do a lot of the grunt work of analysis for you, and even predict your future performance.

A reminder that all of the data is great, but you get the most out of your training log when you put in subjective details. How was your sleep? Did you have external stress that may affect your training? Were you sick? How were your legs feeling? These details really help to flesh out your training log, especially when reviewing it months or years later through the foggy haze of memory.

Roete et al. 2025 – Looking for Patterns of Success and Failure

Roete et al. 2025 – Looking for Patterns of Success and Failure

Rob Lamberts and Teun van Vliet are two of my colleagues who have done a lot of work over the past decade deciphering the actual demands of elite male and female cycling. In a recent article in the International Journal of Sports Physiology & Performance [Side note – a big career milestone for me will be taking over as the Editor-in-Chief for IJSPP in 2026!], their group analyzed the training and racing data of professional female cyclists over multiple years (Roete et al. 2025). The goal was to see whether there were patterns characteristic of highly successful versus less successful seasons.

14 riders participated, with an average of 3 seasons per rider (43 seasons total) spanning over 7 years (2013-2019). Not outright stated, but they were all from a single World Tour women’s team. Over the 7 years, the team used SRM, Pioneer, then Shimano power meters.

As UCI points scoring changed several times over this time window, ProCyclingStats points ratings were used instead as the scoring did not change. Seasons were categorized as “Highly Successful” (HS) if riders averaged ³ 5 points/race over the season, and “Less Successful” (LS) if < 5 points/race.

Duration, distance, power output (PO), heart rate, and kilojoules burned were extracted from the files for both training and races. Mechanical energy produced was calculated as mean power output multiplied by duration. Training Stress Score (TSS) was calculated based on FTP, which itself was calculated as 95% of the highest 20 min mean power output during a season.

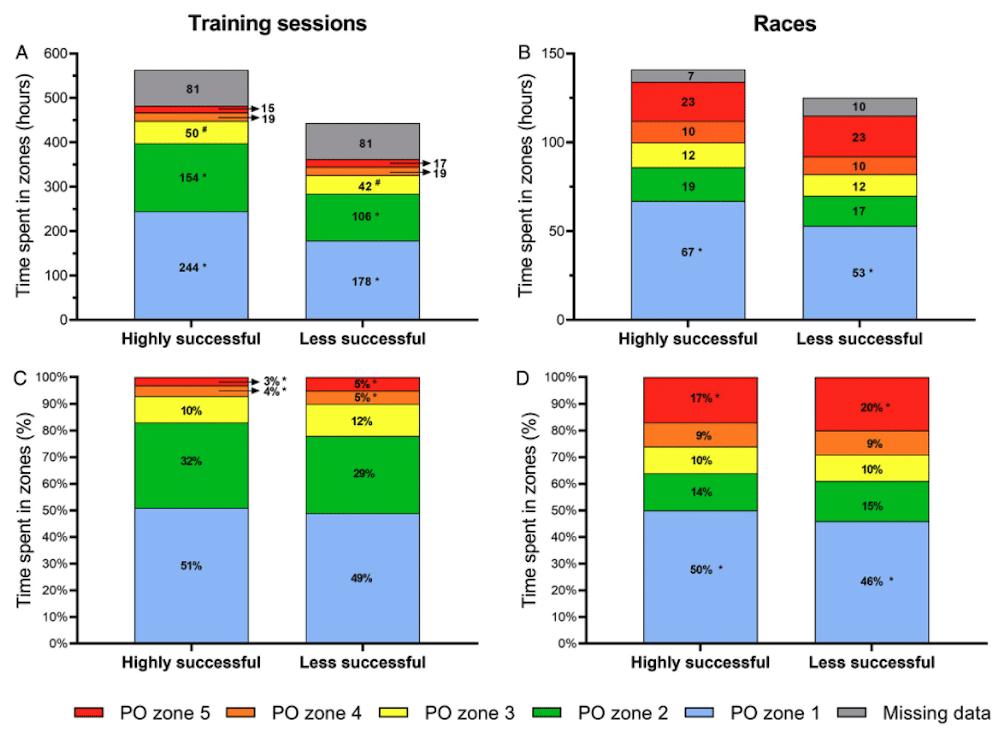

5 training zones were calculated as 1: <55% FTP, 2: 56-75%, 3: 76-90%, 4: 91-105%, 5: >105%.

Internal load was determined by each rider subjectively rating the overall session rating of perceived exertion (sRPE, an overall subjective rating of how hard the entire session felt) from 6-20, then multiplying this by the duration of the session.

Predictors of Success?

This study was nicely designed in that it was not focused on just one rider, and represented a cross-section of rider specialties and team roles. Of the 14 riders, 7 cyclists had 3 seasons included, 1 had 4, and 2 had 6 seasons, representing a good sampling.

Of the 43 seasons analyzed, 18 were classified as highly successful (3938 training session, 814 races), averaging 11.5 PCS points per race. 25 were classified as less successful (5098 training sessions and 1160 races), averaging 0.5 PCS points per race. This wide difference provided good confidence that there was true separation in the categorizations.

Intuitively, FTP was higher in HS seasons (275 W) than in LS seasons (252 W). This likely wasn’t due to more training or racing days but the total and average training duration and work was higher in HS. And as no difference was seen in mean power output or work per km, it appears success came through MORE quantity rather than intensity.

Success also seems affected by riding longer and harder races, with average duration, distance, total work completed per kilogram, and TSS per kilometre during races higher in HS.

With training intensity, HS had less relative time spent in zones 4-5, with no difference in zones 1-3. This suggests that riders may not have been burning themselves out through hard training, but rather using races to gain fitness.

When it comes to races though, HS seasons saw riders likely riding smarter, with less relative time in zone 5 and more in zone 1 (no differences in zones 2-4). This likely involved better positioning and tactics rather than pointless aggression.

What Can We Learn From the Pros?

Learning how sport scientists analyze pro riders’ training diaries can definitely be translated to our own riding and racing. What are some of my takeaways?

There seems to be no substitute for quantity of training. Besides being consistent in frequency, the more time you can put into training, the fitter and more successful you’re likely to become.

Not just more training, but more disciplined training at lower intensities, seems to be key. Note how the absolute time spent in zones 4-5 (pink and orange in plot A) didn’t increase, but rather big absolute increases in the less intense zones 1-3.

When racing, learning to draft within the pack and hide from the wind seems critical. This allows you to put your more intense efforts to where they’ll make the biggest impact on the race, rather than wasting those efforts getting you into the right position. So hone your technical skills.

Ride/race fast and have fun!

References

Roete AJ, Erp T van, Elferink-Gemser MT, et al (2025) Internal and External Load Characteristics in Professional Female Cyclists During Highly Successful and Less Successful Seasons. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 20:1224–1231. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2024-0365

Like PEZ? Why not subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive updates and reminders on what’s cool in road cycling?