For those of you concerned about the recent rise of Reform UK and Nigel Farage, it may be worthwhile paying close attention to the route of the 2027 Tour de France’s British Grand Départ when it’s unveiled late next year.

Because, according to a new academic study published this week, hosting cycling’s biggest race can help reduce electoral support for far-right political parties in towns and cities the Tour passes through, a phenomenon that becomes even greater when a French rider wins a stage.

Yes, that’s right – Thibaut Pinot and Romain Bardet may have been France’s most effective bulwarks against far-right extremism over the past decade.

And while all that may sound slightly random, first we need to provide a bit of context. Professional cycling, as we’ve seen all too clearly in recent weeks at the protest-affected Vuelta a España, is an inherently political sport.

After all, unlike other sports that are confined to stadiums, sheltered from the outside world, road racing interacts with that world at all times, passing through deindustrialised towns, bustling cities, and struggling rural landscapes, and across national, regional, cultural, and language borders.

Stage seven, 2025 Tour de France (credit: Zac Williams/SWpix.com)

Stage seven, 2025 Tour de France (credit: Zac Williams/SWpix.com)

In fact, politics has been deeply ingrained in cycling since the beginning. L’Auto, the predecessor to L’Équipe and the newspaper which founded the Tour in 1903, its yellow pages providing the colour of the race’s iconic leader’s jersey, emerged from the bitter squabbles that characterised the Dreyfus affair, one of the most significant political scandals in modern French history.

The Tour of Flanders was the product of the bourgeoning Flemish independence movement of the early twentieth century. Franco’s Falangists used the Vuelta as a means of forcing Spain’s divided people back together, whether they liked it or not. Gino Bartali’s 1948 Tour victory famously, and apocryphally, pulled Italy back from the brink of civil war.

And now, nation states with huge oil reserves and questionable human rights records lend their names to Tour de France-winning teams, and protests over a genocide in the Middle East can bring a grand tour to a grinding halt.

Can the Tour de France instil a sense of belonging in communities which have been “left behind”?

So, it should be no surprise, then, that the spectacle of the Tour de France passing through your town or village, with all its heady, technicolour excitement and Haribo-throwing race caravan, can have a profound effect on your voting patterns.

Or at least that’s the conclusion of a group of political scientists and data analysts, who this week published a working paper on the relationship between La Grande Boucle and the electoral success of the far right in France.

Crowds watch the final stage of the 2025 Tour de France Femmes (credit: ASO/Pauline Ballet)

The study, titled ‘Cycling Through Elections: The Political Consequences of the Tour de France’, is the work of Ala Alrababah and Germain Gauthier of Bocconi University’s department of political and social sciences in Milan, Maelle Delouis-Jost of the University of Zurich’s sociology department, and Adam Polak, a computer scientist at Bocconi.

The researchers aimed to identify whether the “brief but highly visible” nature of playing host to part of the Tour de France route, which combines increased local economic activity with symbolic recognition on a national scale, has an influence on voting patterns in areas which are commonly viewed as fertile ground for far-right politicians.

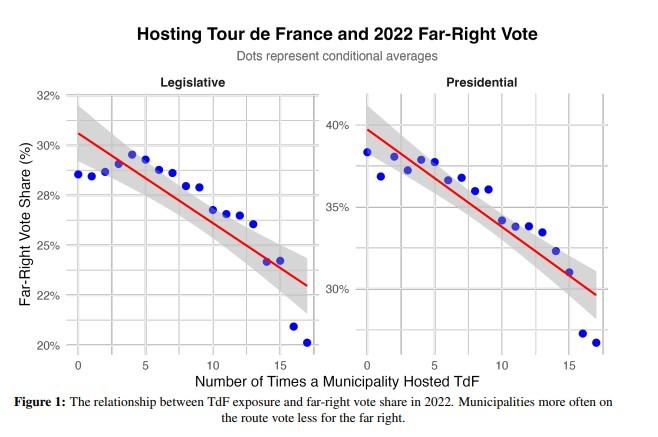

Assessing voting patterns across France at the 2022 presidential and legislative elections – which saw the far-right National Rally party pick up their highest historic share of the vote to date, 23.2 and 19.7 per cent respectively – the researchers found a strong correlation between the areas which host the Tour more often and those which are less likely to vote for the far right.

Effect of hosting the Tour de France on far-right vote in France (credit: Ala Alrababah et al)

Effect of hosting the Tour de France on far-right vote in France (credit: Ala Alrababah et al)

“These patterns raise a broader question,” the researchers noted. “Can brief interventions that increase visibility and economic activity, such as sporting or cultural events, affect vote shares for far-right parties in peripheral regions?”

They pointed out that communities that have experienced deindustrialisation, weak labour markets, and population decline have proved key to the rise of radical right-wing parties across Europe, with politicians capitalising on the narrative that these areas have been “left behind” by the political establishment.

“Residents of peripheral communities often feel neglected or invisible, which fuels a sense of lost status and resentment toward metropolitan elites,” the study says. “Given these accounts, one might expect temporary interventions like the TdF to matter little for political behaviour.”

However, by comparing the route of the Tour de France between 2002 and 2022 and France’s electoral results during that same period, the researchers found that support for the far-right fell in places visited by the Tour, thanks to both the resultant economic activity and the sense that the area was being recognised at a national level and no longer neglected.

Saint-Meen-Le-Grand, stage eight, 2025 Tour de France (credit: Zac Williams/SWpix.com)

Saint-Meen-Le-Grand, stage eight, 2025 Tour de France (credit: Zac Williams/SWpix.com)

According to the study, exposure to the Tour de France reduces the far-right vote share by 0.03–0.04 standard deviations on average between 2002 and 2022, equating to a 0.33 percentage point decline in the far-right vote share in presidential elections and a 0.44 percentage point decline in elections to the National Assembly. This effect is strongest in poorer areas and in towns with high prior support for far-right parties and politicians.

The Tour de France’s effect on voting patterns has also increased in recent years, alongside the growing far-right vote. In 2022, for example, the most successful year for Marine Le Pen’s National Rally in its history, the Tour de France was responsible for 0.13 standard deviation reduction in the far-right vote at the presidential election and 0.16 in the legislative election.

“During our study period, far-right support was highest in the 2022 legislative and presidential elections, which likely brought in many first-time, less committed voters and could help explain why the TdF produced a larger effect that year,” the researchers said.

According to the researchers, this reduction in the far-right vote owes to the “symbolic recognition” afforded by the Tour de France, which broadcasts “peripheral” towns to a national audience and “frames them as part of the collective story of France”, providing visibility and sense of belonging that undermines the narratives of neglect and alienation on which radical-right appeals rely.

Thibaut Pinot versus Marine Le Pen

Beyond the general impact of Tour exposure on a community’s sense of pride, support for the far-right is also reduced in areas that play host to a French stage winner, with home victories associated with an additional 0.019–0.020 standard deviation reduction in the far-right’s vote share.

Pinot battles to third on the stage to Mende at the 2022 Tour de France (credit: Zac Williams/SWpix.com)

Pinot battles to third on the stage to Mende at the 2022 Tour de France (credit: Zac Williams/SWpix.com)

A French stage win, the researchers say, especially on the Tour’s increasingly global stage, is received as a “national moment”, validation to spectators at home that “their” country still counts in a race that has long cast off its parochial shackles and embraced internationalism, and one that has now gone four decades without a French yellow jersey winner.

This phenomenon was enhanced further when recently retired French heroes Thibaut Pinot and Romain Bardet – who carried the biggest hopes of breaking that 40-year duck over the past decade – raced through their home regions.

The study noted that, when the Tour passed through Pinot’s home turf of the Vosges in 2019 and 2023, “crowds filled the valleys chanting his name, while national outlets likened the atmosphere to a family reunion, given the visible identification between rider and supporters”.

Alongside the ‘Bardet-mania’ that gripped the Massif Central during the French climber’s career, “these cases suggest that a French rider’s presence on television, cheered by clearly invested supporters, can make entire communities feel recognised.”

Romain Bardet, 2024 Tour de France (credit: Zac Williams/SWpix.com)

Romain Bardet, 2024 Tour de France (credit: Zac Williams/SWpix.com)

The study also found that the Tour de France has a noticeable and significant economic benefit in areas typically seen to be in economic decline, and therefore susceptible to far-right narratives.

Exposure to the Tour, the researchers found, boosts local GDP per capita by 0.14 per cent, or €56, relative to the national average (though there is no real effect on employment rates).

Meanwhile, the researchers conducted short field surveys before and after the 2025 Tour, which found that residents living in towns which hosted this year’s race professed more pride in their local community than those who weren’t visited by the Tour.

Many respondents to the survey highlighted the pride and recognition that came from seeing their community on national and international television broadcasts, with one explaining that “seeing the town highlighted on a national and international scale strengthens the sense of belonging, with decorated streets, media presence, and a festive atmosphere.”

Tadej Pogačar signs autographs, stage nine, 2025 Tour de France (credit: Zac Williams/SWpix.com)

Tadej Pogačar signs autographs, stage nine, 2025 Tour de France (credit: Zac Williams/SWpix.com)

Another respondent noted that the Tour made them feel “as if my town really exists” and that it “brought people together”.

“While economic decline matters, recent research shows that perceptions of invisibility and loss of standing also influence support for the radical right,” the researchers concluded.

“Using the case of the TdF, our analysis shows that even short-term, high-profile interventions can reduce extreme political preferences in economically marginalised areas.

“Structural disadvantages are persistent drivers of extremism. Our results show instead that discontent in such places can be more elastic.

“Municipalities exposed to the TdF experience significant declines in far-right support, with the largest effects in poorer areas and towns where the far right was already strong.”

Peloton rolls out of Bayeau, stage six, 2025 Tour de France (credit: Zac Williams/SWpix.com)

Peloton rolls out of Bayeau, stage six, 2025 Tour de France (credit: Zac Williams/SWpix.com)

They continued: “These patterns suggest that anti-establishment voting in left-behind places is not fixed and appears responsive to salient place-based interventions.

“While we do not argue that brief cultural events substitute for structural investment, our evidence shows that they can generate reductions in protest voting and may complement long run efforts to address disadvantages in peripheral areas.”

Now, I wonder what effect the Tour de France will have on Britain in 2027…