Slathered in respect by all corners of the musical spectrum, Interpol have been delivering their brand of darkly-hued, and masterfully crafted, indie rock since their critically revered 2002 debut, Turn On the Bright Lights brought them to global attention.

Although we’ve had six superlative Interpol records since, it’s still the fractured, widescreen intensity of that first album that stands as the immovable summit of the band’s discography.

Perhaps the long-tail endurance of Turn On the Bright Lights is in part down to its historical context. Written gradually over the many years of blood, sweat and tears that preceded their being signed, the album was launched into a recently resuscitated indie rock market.

Having been re-energised by the sudden emergence of the Strokes, indie guitar bands (preferably with a New York flavour) were en vogue.

Interpol, however, were anything but coat-tail hangers

You may like

Musically, the band was directed by the assured hands of guitarist Daniel Kessler and expressive vocalist and lyricist Paul Banks. Operating within a uniquely shadowy universe that concocted a massive sense of scale via intricate, delay-soaked guitar, Interpol were musically captivating. Yet, while often finely drawn, the group’s sound could lurch into pits of ferocious, post-punk fire, replete with fascinating, elusive lyrics.

Journalists of the day, of course, scurried to find the connective tissue. Yes, there was quite evidently inspiration from the murk and doom of Joy Division and Echo & the Bunnymen, but so too could be sensed that same crazed jitteriness of early Talking Heads, Magazine and The Chameleons.

But whatever their touch points, Interpol were no nostalgia act.

Rising out of a New York still reeling in the wake of the cataclysmic terrorist attacks of 9/11, early Interpol jibed with an omnipresent paranoia.

The four piece had already established a small cult following in the years preceding their debut’s release. At that stage, however, the band had become aware that the mood of their downcast, monochrome canvas wasn’t going to find favour in the then-pop saturated charts.

The band had been through a lot since their inception in 1997. Kessler, Banks, bassist Carlos Dengler and drummer Sam Fogarino had already penned a growing stable of songs, had recorded innumerable EPs and danced to the tune of a conveyor belt of labels. A record deal, however, was always out of reach.

(Image credit: Wendy Redfern/Redferns/Getty Images)

By the summer of 2001, Banks and Kessler were becoming resigned to the idea that Interpol would likely be a niche concern, forever.

Then, in July 2001, Is This It hit shelves.

That blinding first Strokes LP detonated like a neutron bomb, opening up a new frontier for commercially viable guitar rock with attitude. All eyes suddenly swung, Sauron-like, towards the New York scene.

You may like

As the fertile ground on which rock’s newest great hopes sprang from, what else had the city that never sleeps been brewing within its dankest clubs?

“It really wasn’t until the Strokes broke that anybody started talking about the New York scene,” Paul Banks told Pitchfork. “There was some protection in the idea that there was this romantic moment happening among musicians, but that didn’t really exist. So, historically, it was definitely a scene, but not the kind of scene where we were all feeling it at the time.”

Suddenly finding themselves fashionable in this burgeoning new market, interest was piqued in Interpol’s heavily road-tested blend of post-punk influences.

Matador, one of that cavalcade of labels that had previously rejected the band’s first two demos, hurriedly got back in touch after hearing their third.

“We got in touch with them and set up a meeting,” recalled Matador Records’ founder Chris Lombardi in an interview with Magnet Magazine.

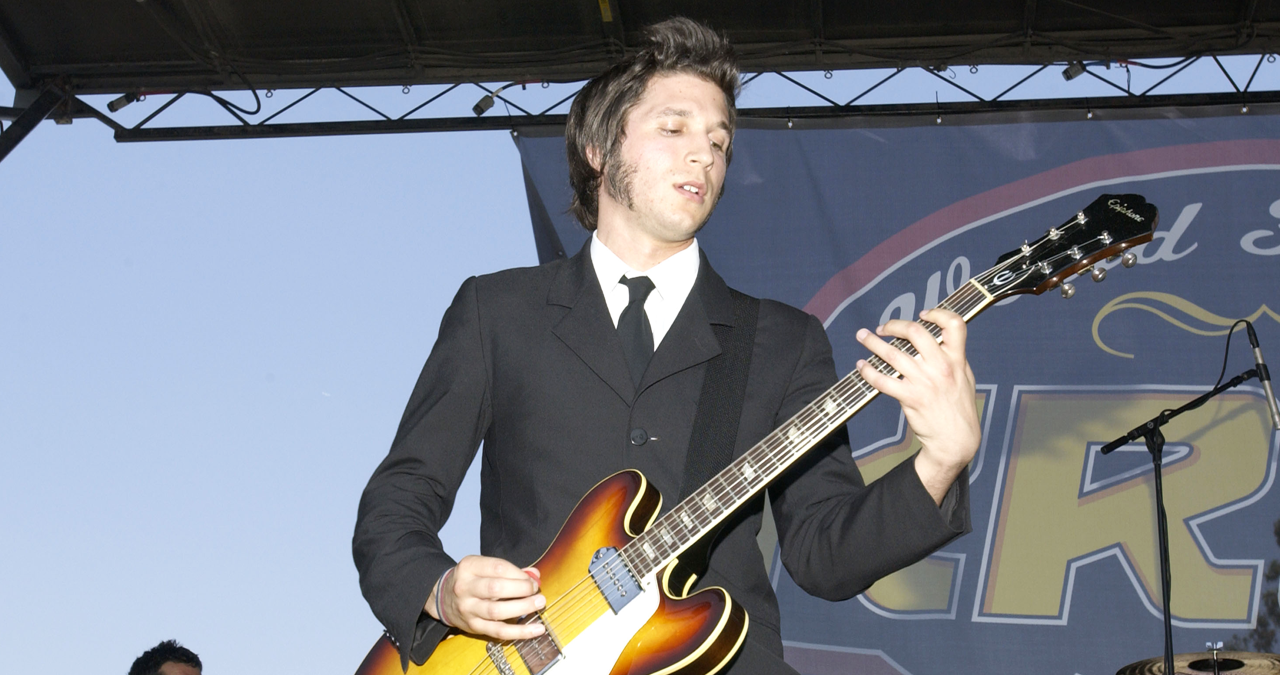

“They were really unusual. Very confident and ready to tend to some business. They were all wearing suits and were considerably better dressed than we were. Their shoes were shined. It was like meeting with a bunch of young lawyers. They were fans of the label, had great taste and a very clear idea of what they wanted to do after recording. We quickly became comfortable with the idea of signing them.”

(Image credit: Kevin Winter/Getty Images)

With Matador’s backing, the band could finally get to work on their first full length album. “We’d been playing around New York for a long time without getting anywhere,” Kessler told Spin. “When we signed with Matador, we would’ve been thrilled with selling 10,000 copies. We just wanted someone to pay attention. We didn’t care why.”

The album that would become Turn On the Bright Lights was recorded in November 2001 with Gareth Jones and Peter Katis as Tarquin Studios in Connecticut. Fortunately, the four men had amassed great body of work from which to cherry-pick, refined for years on the live circuit.

There was the scene-setting atmospherics of usual gig-opener Untitled, the melancholic desolation of NYC, the choppy energy of PDA and the final, pulsing glorious ascent of Leif Erikson. Despite these succulent cuts, Kessler and Banks trimmed off several songs from their set that were now looking a little ragged.

These were to be replaced by a clutch of new songs that would bolster the album’s strongest tentpoles, worked out prior to the recording sessions proper.

Among these new offerings, would come the song that would ultimately be the one that would grab a generation of listers. It would be this track, above all others, that would be the record’s most adept missionary. Coaxing and converting a flock to the church of Interpol.

Then going by Kessler’s working title, ‘Obstacle 1’, the pulse-pounding energy of the track perfectly defined everything that made Interpol brilliant in a little over 4 minutes.

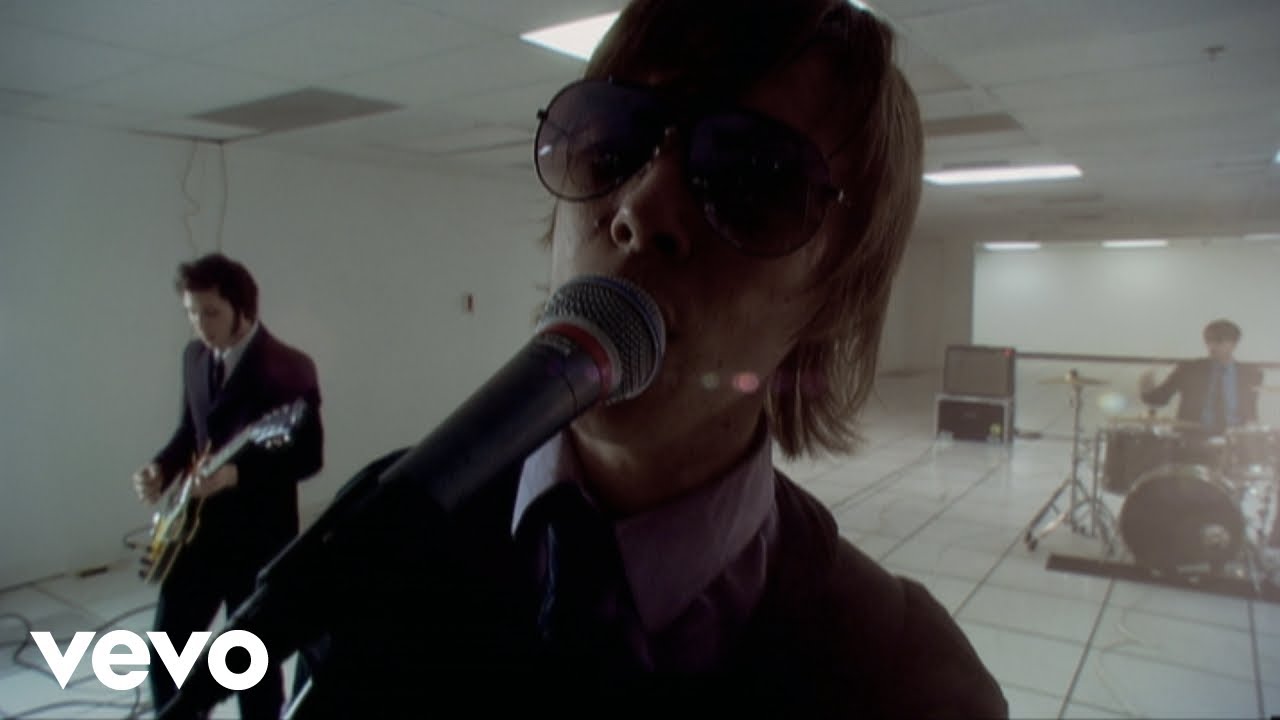

Interpol – Obstacle 1 – YouTube

Alongside its sibling, Obstacle 2, the track was all but completed from a musical standpoint by the time Banks set to work on its lyric.

The titular ‘obstacle’ was apparently an in-joke allusion to the fact that the band were trying to navigate an unexpected creative brick wall. Trying to write something that could stand toe-to-toe with the strongest parts of their stable, it seemed, was trickier than first assumed.

“We wrote Obstacle 2 first and Obstacle 1 second, and I do think it was relating to the fact that, for some reason we’d had a drought in our writing,” Banks recalled in an interview with Pitchfork in 2003.

“We kind of had a down phase. We just hadn’t written anything good in a couple of months, and all of a sudden we were pumping out songs. So it was sort of related to that.”

Rooted in a triangular dance between the three notes of the F Major triad (F, A and C) the music of the majority of the song was tensity manifest.

Kessler’s syncopated lines interwove deftly. From the intro onwards, Daniel’s bass notes maintained a stable F to A major root, while the higher strings swooped between the notes of C, A and then returned to a higher C.

The higher guitar line’s swerves between notes anticipated the coming root note change – and hinted at some ambiguity in the major/minor stakes.

Musically speaking, these teetering on-the-brink areas which blur the lines between conventional keys would become a favoured location for Interpol over their career.

(Image credit: L. Cohen/WireImage)

Atop this came further guitar work, as Kessler daubed rhythmic punctuation and additional guitar lines. They were pummelled along by Fogarino’s frenetic beat and Dengler’s staccato, Peter-Hook-recalling bass part.

It was an irresistible combination, a collision of old influences and urgent, impetuous energy.

“For me, it was like having John Bonham in the band,” said Dengler of Fogarino’s notably superb drumming. “Like the best of both worlds: I can be in the pure universe of floating melodies and melancholy textures, but underneath I get my Bonham fix, where I can land my bass notes.”

The overall effect was a musical foundation that was both strident yet pained. Emotive and agitated but seemingly riddled with remorse.

It was a mood that Banks would take the lead from when it came to penning his lyric.

Banks, an English and Comparative Literature major, had developed a penchant for alluring wordplay and a turn of tangled phrase. Unusually, he decided to leave Daniel’s demo name well alone, channelling the curious intrigue of the titular ‘obstacle’ into his words.

“He wrote those [Obstacle 1 and 2] songs in succession, and those were his working titles, and although I typically write the lyrics and titles, if you already have a dope title for a song I’m smart enough not to f**k with it,” Banks told Magnet Magazine.

It wasn’t until a trip to Tokyo to visit his father, that Banks finished the lyrics for Obstacle 1.

Depicting a crumbling relationship, Banks’ words painted a vivid, internalised sketch of the conflicted feelings within a dying romance.

Resentment and desire butt heads in this rail against the insurmountable obstacle of communication breakdown. It married well with the album’s broader theme of urban alienation.

I wish I could eat the salt off

Of your lost faded lips

We can cap the old times

Make playing only logical harm

Though the verses and choruses teared over the surface of Kessler’s taut musical framework, the lengthy, back-and-forth outro served as a more restrained coda to the narrative.

When it came to tracking Banks’ vocal, he affected his signature intensity-rising delivery, becoming fully histrionic during the chorus.

(Image credit: Ross Gilmore/Redferns/Getty Images)

“My vocal style was affected by New York City,” Banks explained to Pitchfork “When you get in an 11-by-10 room with a drummer beating the s** out of a kit, shouting becomes the M.O.”

This characteristic vocal style would become de rigeour for Banks in the ensuing years, with the similar-sounding Evil from the band’s follow-up Antics continuing this trend.

The chorus’s ferocity was underlined by the repeated motif of ‘Stabbing yourself in the neck’. A suitably violent turn of phrase which was, unbeknownst to Banks at the time, set to become a late-night, indie-club singalong staple.

As a group of four men who’d already been through the wringer as a band before they’d got signed, the palpable anxieties on the record were not entirely artificial.

Sometimes the band themselves could explode. One such day was, according to Sam Fogarino, the very day that Interpol tracked Obstacle 1.

“We all respected one another and what each of us brought to the table, but we could also challenge each other intellectually, and more,” Sam told Magnet Magazine. “Ultimately you’d get p*ssed off enough and then record Obstacle 1 or something. I’m sure Carlos and I got in a full-blown fight that day.”

Released as the record’s second single on November 11th 2002, Obstacle 1 (backed with a superb Floria Sigismondi-directed video) soon entranced millions of new fans. These were people who’d been long crying out for someone to seize that cobweb-trailing baton of gothic, artful post-punk.

For many, they didn’t know they needed a band like Interpol in their lives, until they blazed through that indie scene in the early 00’s.

(Image credit: Wendy Redfern/Redferns/Getty Images)

Many of these newly bowled-over listeners sought out the band’s debut, soon falling under its spell. “Interpol’s debut album is a masterclass in dynamic atmospherics and artful rock ‘n’ roll,” reminisced Sterogum in a twenty-year retrospective. “At its best, this thing just soared, and Interpol’s commercial prospects soared right along with it.”

As for Interpol, the band continue as a vibrant creative unit, with their latest record, The Other Side of Make-Believe dropping in 2022.

“It’s never really scripted, we never plan what we do next,” Daniel Kessler told this writer in an interview for Guitar.com. “As long as we still have that chemistry, we’ll keep making music. We don’t know what’s going to come next, and I value the time to have experience, travel, inspiration and meeting new people. It all becomes information that fuels you and the writing.”