Sir Andy Murray’s morning ritual is a vision of retired suburban bliss. After dropping his kids off at school, one of Britain’s greatest sportsmen heads to Beaverbrook Golf Club and passes his suddenly empty days by hitting balls on the driving range.

Alas, the indefatigable spirit that carried Murray to three grand-slam singles titles and through so many pain barriers is not so easily unlearned. The stories of members spotting him practising before they tee-off, only to find Murray still there when they finish their round four hours later, have become folklore at the highly exclusive club near Leatherhead, in Surrey. Since his long farewell at Wimbledon and the Olympics last year, he has gone from barely swinging a club to protect his aching body to being on the cusp of becoming a scratch golfer.

“My kids think I’m a golfer. They say, ‘Daddy, why do you play every day?’ ” Murray, 38, whose handicap is now 2.4, says, laughing. “I didn’t really play for 12 years because I had a back operation in my mid-twenties and I was sore when I practised. Thankfully, it’s been pretty good since I finished — I think tennis was the main issue — and I just really enjoy it.

Murray won Wimbledon in 2013 and 2016, ending a 77-year wait for a men’s singles champion

KIRSTY WIGGLESWORTH/AP

“I guess it has filled a bit of a void. It is something to practise and get better at and there are so many different parts of the game you can work on, and I don’t find that boring. If I don’t have any commitments, I’ll arrive at 9am and stay there until I have to pick the kids back up from school.

“I think that comes from my career as a professional athlete. I’m used to spending all day at the training centre and going to the gym, doing your physio work, that’s normal for me. I know I’m doing more than most but I’m in a position where I’m able to because I don’t have to work during the week.”

But being Murray, it is never quite that simple. The tears and self-flagellation that became such a feature of the British summer have not yet translated to the golf course, nor are there a string of broken clubs to match the misbehaving rackets that met a swift demise. But for a child from Dunblane, Scotland who “never would have thought I’d play at Wimbledon”, let alone end the 77-year wait for a British male singles champion, there must always be an outsized goal, a kind of Herculean task that only someone with his graft, gumption and capacity to suffer could muster.

In Murray’s new life, that goal is a tilt at regional qualifying for the Open Championship in 2027. Any amateur or professional in the UK with a scratch handicap can enter for a fee of £200. Around 2,000 players take part, with roughly 100 making it through to final qualifying, from which at least 16 will qualify for golf’s oldest major. Murray is not under any delusions that he will make it all the way to St Andrews, but he still craves the stimulation of genuine competition. A debut at the Alfred Dunhill Links Championship, a DP World Tour event in which an amateur is paired with a pro, at the start of October is a trial run. Murray has also signed a sponsorship deal with club manufacturer Callaway, who are arranging for him to have lessons with renowned coaches.

Murray’s wife, Kim — with whom he has four young children — regularly sat in the players’ box and lived every scream

DARREN FLETCHER

“A couple of my friends who are very good golfers have done it. If I can improve enough, I think it would be a fun thing to do,” he says. “I played in the club championships at Beaverbrook a few months ago and I loved it. It was the most fun I’d had playing golf and the more I play, the less I enjoy just playing socially. I don’t know if I’ll be capable of entering, but I want to try and play in a few more events. I’ve been pretty amazed at how willing the pros are to help because spending five hours with people who are hacking it around probably isn’t that enjoyable.”

‘I just wanted to play Wimbledon one more time’

Such was Murray’s bitter refusal to give up tennis, he presumed — like so many of us — that he would struggle dearly without it. It was 2017 when he returned to Wimbledon as the defending champion for a second time and as the world No1 but realised his hip was wrecked. A year later, he left a near-empty stadium at 3am in Washington sobbing in spite of victory because he knew yet another surgery had failed.

Murray never reached the fourth round of a grand-slam tournament again but he continued to rage, vividly and agonisingly, against the dying of the light, persisting through more injuries, dropping down to the unglamorous second-rung Challenger circuit, and summing up new depths of resolve for another Wimbledon epic. Murray’s final farewell in SW19 last summer epitomised all that and more as he hobbled around the court alongside his brother, Jamie, in the first round of the men’s doubles despite a cyst in his back and a doctor’s advice to pull out.

“The issue wasn’t the pain. It was that I didn’t have full control of my leg because one of the nerves in my back was compressed by the cyst, but I just wanted to play at Wimbledon one more time,” he says.

Andy’s final match on Centre Court, a doubles defeat with his brother Jamie, was followed by a lengthy farewell presentation

SUNDAY TIMES PHOTOGRAPHER MARC ASPLAND

The brothers sat courtside as the presentation brought down the curtain on Andy’s career

TIMES PHOTOGRAPHER MARC ASPLAND

In his 2019 documentary, Resurfacing, Murray described the scars that punctuated his childhood in a voice note because he did not feel comfortable speaking about them on camera. He was nine years old when Thomas Hamilton shot dead 16 schoolchildren and one teacher at Dunblane Primary School. Within the next year, his parents, Judy and William, were divorced, and then Jamie, who is a year older, moved away from home to focus on his training. “My feeling towards tennis is that it’s an escape because these things are stuff that’s bottled up,” he said.

Murray’s fear was that they would start to pour out without it. Only this week, Bjorn Borg revealed for the first time in his autobiography that he almost died twice from drug overdoses in the years after retiring from tennis. In the months before that final Wimbledon appearance, Murray even began seeing psychologists to try to prepare himself for the unwanted transition.

“I expected to really miss it because I love tennis,” he says. “I didn’t stop because I was not enjoying it any more, I stopped because I physically couldn’t do it at the level I wanted to, and there are lots of stories of athletes who finish their career and within a year or 18 months they have spent all of their money or they are struggling with their mental health, so yeah, that was a concern, to be honest. I spent time in the build-up [to retirement] talking to psychologists about how I was going to go about doing that.”

But what quickly becomes clear when speaking to Murray in a rare interview is that he does not yearn to turn back the clock much at all. His trophies and accolades, which include two Olympic gold medals, a Davis Cup and 46 ATP Tour titles to go with his US Open (2012) and Wimbledon (2013, 2016) crowns, are all kept in the basement of his house. The only photographs he has from his career, in which he earned nearly £50million in prize money on the court alone, have all been consigned to one room.

“That’s actually the downstairs toilet,” he says. “My kids aren’t really interested or bothered about what I did for my career. Right now, I don’t hit balls, I don’t practise, I don’t ever go on a court unless my kids or my wife want to play, so, yeah, I just don’t miss it. To be honest, it’s not been difficult at all. I’ve really enjoyed my life away from tennis.”

Nor does Murray watch it much either since the end of an unexpected six-month stint coaching Novak Djokovic in May. The mesmerising French Open final between Carlos Alcaraz and Jannik Sinner at Roland Garros in May? “I heard it was an amazing match,” he says. Their rematch at the US Open this month? “I was on a plane to Ireland [to play golf]”.

‘Alcaraz is a very average golfer’

The only real enthusiasm he reserves for his old love is when discussing fellow golf fanatic Alcaraz, who Murray played a round with before Wimbledon. “He’s a very average golfer, unfortunately for him, but his tennis reminds me of my favourite footballer growing up and I got to see live a few times, which was Ronaldinho,” Murray says.

Alcaraz played golf with fellow Spaniard Sergio García in his downtime during the US Open

KIRSTY WIGGLESWORTH/AP

“They’ve got all of this skill and ability, they obviously want to win, but they play with a smile on their face. If the moment comes to do something entertaining they will, and I think that’s what makes them so absorbing because you never know what is going to happen next, so I particularly enjoy watching him.”

Murray puts his neat sense of closure down to the knowledge that he had rinsed every last drop from his body. “I had put everything I had into it. There wasn’t much left on the table,” he says.

Djokovic, Martina Navratilova and John McEnroe were among those to come out on Centre Court for his farewell, while Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal featured in the montage that documented Murray’s evolution from a surly teenager who did not always enamour himself to the British public to the beloved role model that — if only briefly — finally forged a chink of light between the “Big Three”.

Djokovic, second left, Navratilova, second right, and McEnroe, right, were among those at Murray’s farewell

DARREN FLETCHER

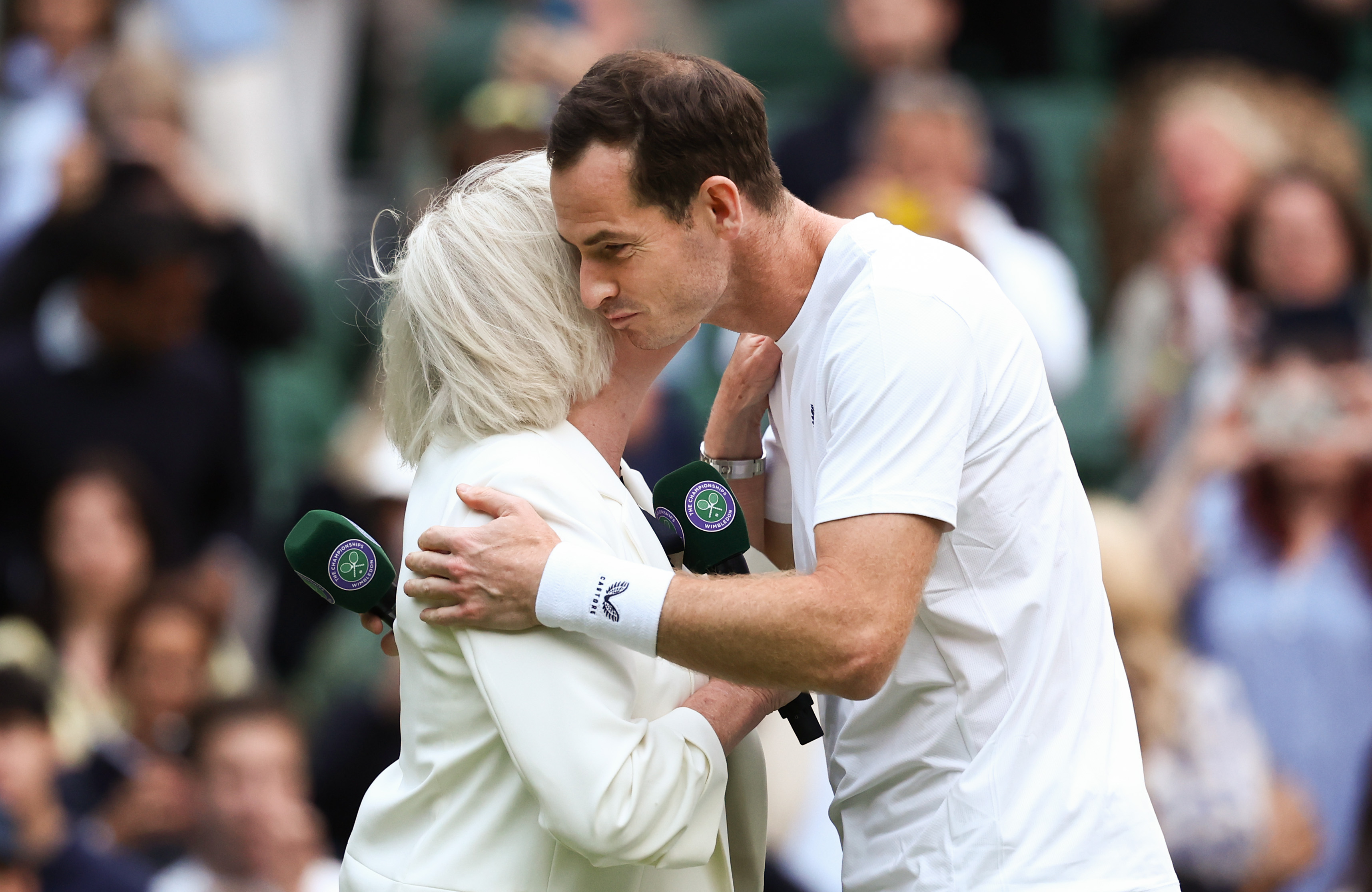

Murray — with Sue Barker — was “very emotional but very happy” at his Wimbledon exit

GFRANCOIS NEL/GETTY IMAGESTTY

“To be honest, when I was on court, my head was spinning. I wasn’t able to concentrate much on the video, but I’ve watched it back,” he says. “I was obviously very emotional at the time. There was a lot going on in my head, but I was also happy. I expected to feel really overwhelmed by the moment but it was just a sign that I was ready. I knew it was the end. It wasn’t the way I had envisaged it, playing doubles, but when I reflect on it, playing with my brother on Centre Court at Wimbledon, it was an amazing way to finish. We’d never got the chance to do that.”

All that being said, when Murray realised he had missed a call from Djokovic while playing golf last November, he felt he couldn’t reject the chance to coach his old rival. Their partnership initially got off to a promising start when Djokovic reached the Australian Open semi-finals, but the clay-court season then brought a series of shock defeats against little-known players, such as Alejandro Tabilo and Matteo Arnaldi.

One video emerged of a training session in Madrid during which Djokovic cursed while Murray handed him a pair of tennis balls. “F*** sport, f*** tennis, f*** everything else,” the Serb said. By the time their split was confirmed, there was a sense that it arrived as more of a merciful reprieve to Murray.

“At the beginning I enjoyed it, but obviously the results were not what I expected, and I’m sure it wasn’t [for Djokovic] as well,” he says. “I’m still glad I did it. It was a unique opportunity, and if I hadn’t, I would have regretted it. To get to spend time with one of my biggest rivals, one of the best athletes of all time, trying to help him and learn from him and understand him was fascinating. But if you want to do a good job of coaching, in my opinion, you need to spend a lot of time with the individual and that’s hard when they don’t live near you.

“A British player would be a lot less demanding time-wise because you don’t have to be away from your family on off-weeks training, whereas Novak was living in Spain at the time so you’re travelling then as well. To do it so soon after I finished playing was difficult. It was still a great opportunity, but it’s not something I would jump into for quite a while. I don’t think I have any desire to do that right now.”

After a promising start, Murray’s spell as the coach of Djokovic did not last long

EDGAR SU/REUTERS

‘Things were fine with Emma after we cleared it all up’

Murray is also reluctant to follow another natural path into punditry. He attempted it once at Wimbledon in 2018 when he commentated on the epic quarter-final between Nadal and Juan Martín del Potro.

Despite Pat Cash once claiming he owned “the most boring monotone voice in the history of the planet”, Murray’s analysis received rave reviews. But, after five hours in the booth, he signed off with the words “well, that was horrific”, and left it at that.

“One of the things I love about other sports like football is seeing a bit more debate between the pundits. It’s interesting for the viewer if you’ve got Jamie Carragher and Gary Neville challenging each other’s views. Everyone sort of agrees with each other on the tennis side of punditry, so it’s not something I hugely want to get into right now,” he says.

Murray did not enjoy his stint in the commentary box with Andrew Cotter, left, and Tim Henman, right

STEVEN PASTON/PA

It is not hard to imagine Murray’s dry, self-deprecating humour lending itself to a Roy Keane-esque role, but that would pose another dilemma. Murray was wounded by the criticism he received early on in his career and has made a conscious effort not to make similar statements about Jack Draper and Emma Raducanu.

“I know when I was a young British player I found it very, very unhelpful when people that you knew or looked up to were being critical of you after losses publicly,” he says. “You respect their opinions and often they might differ from what your coach is telling you. When you’re 20 years old, you’re still responsible for the team that you employ.

Murray was due to play in the mixed doubles with Raducanu, whose withdrawal denied him another chance to play at Wimbledon

JOHN SALANGSANG/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK

“If you’ve got an ex-British No1 or an ex-world No1 saying they don’t agree with how you hit your forehand or the strategy you use in matches, it can be a bit undermining. I know pundits have to do that, but it’s really not helpful for young players, in particular, who maybe are not able to block that out and trust their coaches. If any of the younger British players ever want to talk to me privately, I would always do that.”

Murray has been a mentor to Draper, 23, and the pair practised together countless times at the LTA Training Centre in Roehampton. His relationship with Raducanu, 22, is not as close, with a minor controversy erupting at Wimbledon last year after she planned to enter the mixed doubles with Murray but later pulled out due to a wrist injury. Murray’s mother, Judy, appeared to express her dismay in a comment on social media but later said her post had been misinterpreted.

“We exchanged multiple messages since Wimbledon and things were fine after we cleared everything up,” Murray says. “It was obviously a pretty emotional time for me and everyone around me, so it was hard but, like I said, I was really happy with the way that my career finished. I got to play my last match at Wimbledon with my brother. Emma’s not someone that beforehand we were communicating all the time or discussing ideas about her game and things like that, so that hasn’t changed.”

Murray is hoping to take part in regional qualifying for next year’s Open Championship

It is easy to envisage Murray coaching one — if not both — of them at some point over the next decade. But for the time being he seems to have settled into a state of peace that nobody who witnessed even a fraction of his torment and triumph could ever begrudge. Nor was it ever just him either. For so many years Murray’s wife, Kim, sat in the players’ box and lived every scream and salvo while raising their four young children, Sophia, Edie, Teddy, and Lola. Now, his focus — outside of developing calluses from a new sport — is on what he missed during his career rather than trying to cling onto it.

“My purpose is my family,” he says. “I’m not desperate to go out and explore loads of things because I’m content being at home. Today, I took two of my kids to golf lessons, then I’m going to my son’s football training this afternoon. On Saturdays, we always go out for a family dinner together. I just want to be around for all of those things that I missed when I was playing. I spent so many years away from home, travelling, putting my career first. I feel like I’m making up for that a bit now.”