The Falkland Islands wolf, famously described by Charles Darwin nearly 200 years ago, was unusual in that it didn’t seem to fear humans at all. During his second survey expedition, the naturalist noted it as “a large wolf-like fox”. It was the only native land mammal on the entire archipelago.

But today, in a discovery that is said to have huge implications for conservationists, research has unveiled that the animal was actually the final population of a South American fox that once lived alongside humans.

A new study, conducted by conservation charity ZSL, the Zoological Society of London, reveals that the supposed wolf was not a separate species, but in fact was the final surviving remnant population of the South American fox – an animal that lived on the remote Atlantic islands for another 250 years after its disappearance from mainland South America.

Archaeological evidence suggests the foxes were once kept as pets by hunter-gatherers in South America, long before domesticated dogs were brought to the region.

Darwin noted how the Falkland Islands wolf was easily approached and hunted by settlers, and by 1876 it had been completely wiped out due to persecution and demand for its fur.

Can dogs and foxes interbreed?

What is the biggest wolf in the world? Meet the deadly canine apex predator – as well as its domestic rivals

Previous genetic analysis suggested the animal had diverged from a South American fox (known as Dusicyon avus) about 16,000 years ago. D. avus was believed to have gone extinct at least 400 years ago. But the new paper, published in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, reassesses the data to reveal otherwise.

The finding gives a new perspective on human-caused extinctions, and helps conservationists predict the impact of human activities on wildlife across the globe.

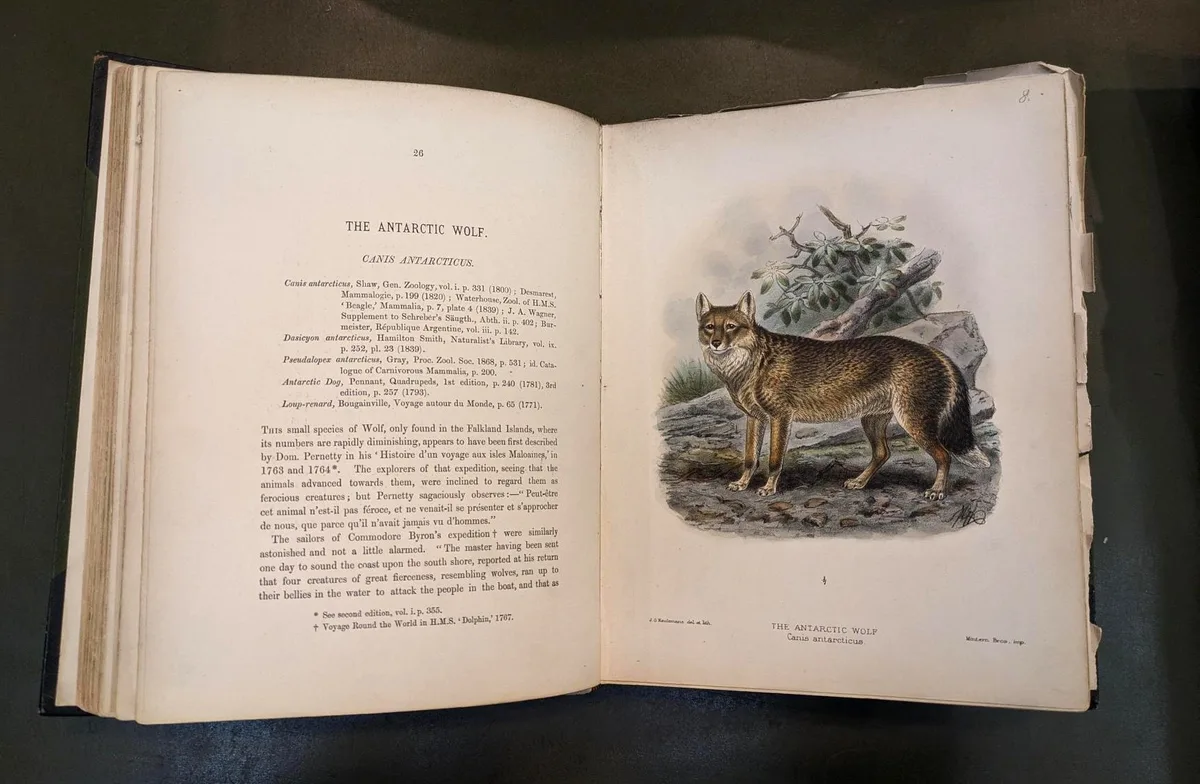

A drawing of the Falklands Islands wolf, at the time named Canis Antarticus, The Antartic Wolf, by J G Keulemans. Credit: ZSL Library

A drawing of the Falklands Islands wolf, at the time named Canis Antarticus, The Antartic Wolf, by J G Keulemans. Credit: ZSL Library

Professor Samuel Turvey, lead author and researcher at ZSL’s Institute of Zoology, explained: “When settlers from Europe first landed on the shores of the Falklands, they were met by a strangely tame, tawny-coloured wolf-like creature – about the size of a small labrador. The naivety that ultimately led to its extinction has traditionally been blamed on the wolf’s isolation.

“Just like the famous dodo, it was thought that millennia of evolution sheltered from the fear of any natural predators, which resulted in a creature that was completely unafraid of people. But the reality was more complicated – and more tragic. The friendliness that made this canine an easy target for hunters was not due to a lack of contact with humans, but because they once lived alongside us.

“This isn’t just a heartbreaking twist to an already tragic story. The finding fundamentally shifts our understanding of what drove this species to go extinct – and has wider implications for our knowledge of human-caused extinctions today.”

Archaeologists have uncovered D. avus skeletons buried in prehistoric human graves in South America, and analysis of one suggests the fox shared meals with ancient hunter-gatherers – strong evidence they were once kept as pets. Other recent discoveries also point to human presence on the Falkland Islands well before Europeans arrived in the 1600s, suggesting that early settlers from South America may have brought these foxes with them.

Turvey went on to explain: “Sixteen thousand years is like the blink of an eye on an evolutionary timescale. It’s comparable to when many British mammals separated from populations of the same species on mainland Europe. New analysis even indicates that D. avus and the Falkland Islands wolf could successfully breed – all of which adds up to suggest the wolves Darwin met were the last survivors of a fox thought to have vanished centuries earlier.

“This means only one member of the fox, wolf and dog family has been driven to extinction by humans since the end of the Ice Age, advancing our understanding of how many unique species we have already lost.”

The team behind the paper suggest D. avus should be renamed to the scientific name for the Falkland Islands wolf – Dusicyon australis.

Realising that D. avus and the Falkland Islands wolf are actually the same species doesn’t just change the story of their extinction – it also offers valuable insights for today’s conservation efforts, helping scientists better understand how human activity impacts wildlife over time.

The finding that the Falkland Islands wolf was introduced to the islands also raises the question of how its arrival impacted the historical ecosystems of the islands – and how that has impacted the region’s biodiversity centuries later.

Samuel said: “We can’t bring the Falkland Islands wolf back, but its story helps us save the wildlife still with us today. By refining our baseline for assessing the vulnerability of species to extinction, this finding allows us to become even better at predicting how threatened species respond to human pressures, and how to plan conservation action as effectively as possible.”

Main image: Drawing of the Falkland Islands wolf by George Waterhouse in Mammal Volume of The Zoology of the Voyage of the H.M.S Beagle. Credit: ZSL Library