“I’m a calm person, I’m patient. If David really starts to get on my nerves, I can have a bit of a Zen moment and just ignore him, if it’s possible to ignore David Walsh,” laughs Pippa York.

“But I’m still wondering, how is this going to work? Oh well, if I do commit a crime, at least I’ll have a good reason for removing this person from the cycling world. And I’ll have saved a number of riders from the humiliation of talking to David…”

York is reflecting on her decision, back in the Covid autumn of 2020, to agree to spending three weeks on the road, following the Tour de France, with David Walsh.

Having resisted the urge to leave the Irish sportswriter on the side of the road and at the mercy of some local bears, those three weeks ultimately turned into three consecutive summers of York and Walsh on Tour. Travelling together, sitting beside each other in the press centre, eating together, checking into the same, potluck hotel together.

At first glance, Walsh and York appear to be something of a cycling odd couple. One’s a talkative Irish Catholic and arguably cycling’s most well-known journalist, famed for his fiery pursuit of doper-in-chief Lance Armstrong. The other’s an introverted Glaswegian Protestant, who earned a reputation as a pro cyclist for offering journalists very little besides a series of one-word answers and a withering put-down.

But, York points out, it all worked out surprisingly well.

“We got on really well,” she says. “We never really fell out. There were a couple moments of tension, as there would be when you’re spending three weeks with somebody. We never really got frustrated with each other, we didn’t call each other names, which is a good point. The whole thing kind of worked.”

Pippa York, British Cycling Awards 2018 (credit: Simon Wilkinson/SWpix.com)

Their travels together during the 2020, 2021, and 2022 Tours – the dawn of the Pogačar age – eventually resulted in a book, ‘The Escape: The Tour, the Cyclist, and Me’, published earlier this year.

Part-travelogue, part-memoir, the book recounts Walsh and York’s time on Tour through the conversations they had in the car and at dinner tables throughout France, as well as providing an unflinchingly honest account of York’s childhood in Glasgow and the gender dysphoria that emerged from the age of five, her career in cycling, and the long and painful process of transitioning.

When York and Walsh first met, as hungry, young representatives of their chosen fields, York was known as Robert Millar.

Millar was one of an exciting crop of pioneering English speakers that headed to Europe alone with their bikes, helping to revolutionise – or, as the marketing people would proffer, ‘globalise’ – the sport as it entered the heady, technicolour age of the 1980s.

During a 15-year career in the peloton, Robert Millar won three stages of the Tour de France, finishing fourth overall at the race in 1984 – a GC result only bettered by a British rider when Bradley Wiggins won the 2012 Tour – and claiming the King of the Mountains prize.

The purest of pure climbers, Millar also finished second once at the Giro and twice at the Vuelta, including the infamous 1985 edition of the Spanish grand tour, when the Scottish rider, then leading the race on the penultimate day, was ambushed by rivals working together to ensure victory for the home favourite, Pedro Delgado.

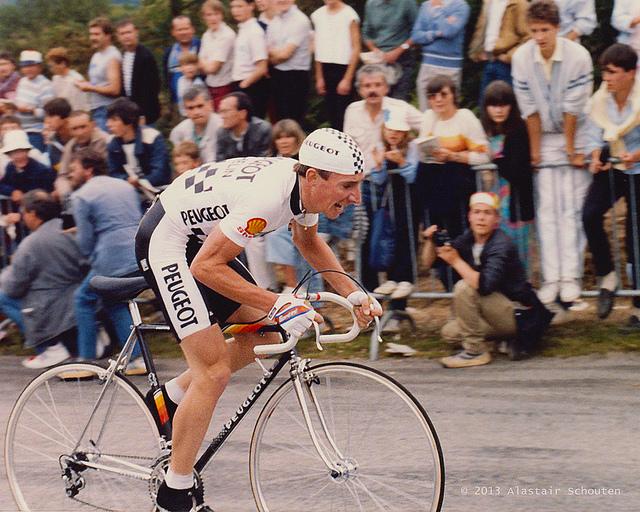

Robert Millar riding for Peugeot in the 1980s (credit: Flickr Creative Commons)

Robert Millar riding for Peugeot in the 1980s (credit: Flickr Creative Commons)

But during those years of success and adulation, Robert Millar hid a secret. From a young age, York experienced gender dysphoria, braving the stairs of the Pollokshaws high rise to venture into town in girls’ clothes. Cycling – both for the escape and the chance to shave her legs without judgement – became the titular escape.

But retirement from the peloton in 1995 brought depression, divorce, a reckoning, therapy, a long, painful transition period, and a private life shattered by the tawdry excesses of the tabloid press. Tentative steps followed during the 2010s, before Pippa York emerged back into the cycling world, and into life on the ‘other side’ – of journalism, that is.

However, speaking to the road.cc Podcast, Walsh admits that during their long weeks spent in the car together, as a self-professed “fanboy” of Robert Millar, he couldn’t quite shake off the Scottish climber.

“When I read back what we wrote about the conversations we had for the book, there was an inner voice in my head saying, ‘David, just let Robert Millar go! Stop haranguing Pippa about Robert Millar.’

“But I genuinely was fascinated by Robert Millar because, for me, Robert Millar is the best British or Irish climber I ever saw. I’d rate Robert Millar, in the pure climber sense, better than Chris Froome. Froome was obviously more of an all-rounder, a brilliant time trialist, and a brilliantly effective climber.

“But if there was a brutally hard Tour de France stage – I’m thinking of the first mountain stage of the 1983 Tour, when Pippa won in Bagnères-de-Luchon, it was chaos, devil takes the hindmost, attacks from the start – Chris Froome wouldn’t have won. But on a day like that, Robert Millar could win.

“So, when I’m in the car with Pippa, I want to know about Robert Millar, I want to find out more.”

.jpg) Robert Millar (credit: Eric Houdas)

Robert Millar (credit: Eric Houdas)

But for Pippa herself, that distinction between Robert Millar The Cyclist and Philippa York is one she also finds to be complicated.

“Who was I, as that person, ‘the cyclist’? Did it come about because of my childhood, and who I am when I’m not being the cyclist, when I’m not in that competition mode?” she says, reflecting on how she dealt with gender dysphoria at the same time as competing for cycling’s top prizes.

“They’re two very different people in the same body and same mind. But I have to have a complete distinction between both of them.

“I fairly quickly separated both issues into compartments – and as cycling took up more of my life, I revisited the gender stuff less. But it would still come up now and again. And that would depend on where I was as a bike rider – the longest time I went for was a year without the dysphoria coming through.

“I have to let go of that competition mindset once the bike race is over, but on certain days it’s quite difficult to do that. And if something happens and my gender dysphoria became apparent during a competition, then that would be quite difficult to process.

“And it could be any little thing, I see something, or someone says something, and that could be a trigger for me to revisit my childhood, or that young person life that I wasn’t having. And it’s quite emotional to talk about it.”

“The cycling isn’t a compensation,” she stresses. “But it allowed me to concentrate fully on the moment, and the gender issues wouldn’t come through. In that sense you can look at it like, because I’m so invested in my cycling career, it allowed me to bury the gender stuff a lot more.

“And there’s a certain amount of truth in that – but I also just wanted to race push bikes, that’s what I wanted and intended to do. And the moments I decided to do that fully, I could forget about the gender stuff.”

Pippa York and Matt Barbet host ITV4’s coverage of the 2022 Tour of Britain (credit: Will Palmer/SWpix.com)

Pippa York and Matt Barbet host ITV4’s coverage of the 2022 Tour of Britain (credit: Will Palmer/SWpix.com)

That single-minded determination to succeed also meant that York soon erected psychological barriers, designed to prevent anything that didn’t equate to better performance and results breaking inside. A handy tool to have when dealing with something so immensely private, and so alien to the queasily macho world of 1980s professional cycling.

“I definitely built barriers to allow myself to function 100 per cent as a bike rider,” York says. “So your life becomes pretty extreme. I wouldn’t be willing to give somebody, like journalists, time if I judged them as not worthy of my time. If they weren’t doing their job 100 per cent, I judged them in the same way they judged me.

“For a lot of people, that was a shock to them. I think a lot of journalists and people in the cycling world believe the rider is an object which they’re allowed to study. I wasn’t of that mindset! I thought, ‘you’re judging me on what I’ve done today, so tomorrow when I read your piece in the paper, I’m going to judge that too, and make a decision whether it was crap or great or whatever’.

“That kind of feedback wasn’t what people wanted, but it enabled me to sift through people that I would give time to, and the others I wouldn’t give any time to, because it affected my recovery. For me, that was an easy decision.

“If I had to give an interview, I would think of how much time and how much of myself I was going to give. And if it started with what I classed as a stupid question, the moments afterwards wouldn’t go very well! Swear words were introduced, and it would end pretty quickly.”

David Walsh (credit: Alberto E. Rodriguez)

David Walsh (credit: Alberto E. Rodriguez)

Walsh, as a journalist tasked with extracting more than just swear words and post-stage grunts from Robert Millar, recognises those barriers.

“It was clear that, like many people, Pippa felt that there was part of her that she wanted everybody to see – and that was Robert Millar, the successful cyclist, very single-minded, very ambitious, and very good at what Robert Millar did,” he says.

“But then there was the part of Robert Millar that Pippa didn’t want anyone to see. And you’ve got this conflict that lots of people have – lots of people spend their lives trying to hide some part of themselves from the rest of the world. It’s part of the human condition.

“But what struck me about Pippa is that Robert Millar had this very successful career, and there was acclamation for Robert Millar, people loved Robert Millar. It wasn’t just that he was a great climber, it was the way he climbed, like a Scottish Van Impe or a Scottish Charly Gaul, someone just born to ride in the mountains.

“But that part of Robert Millar that Robert Millar never wanted anyone to see, it never went away. And no matter how many years had passed, or how much success there was, Robert Millar wasn’t happy being Robert Millar. And that makes me understand the enormity of what Pippa has done.”

“I’m in the car with Pippa travelling from stage to stage, and I’m asking all these questions about Robert Millar. And I find myself reverting to the fanboy – ‘why couldn’t Robert Millar be enough? You were such a brilliant climber!’

“And Pippa looked at me and said, ‘being Robert Millar couldn’t compensate for who I wasn’t.’ And then I feel like an idiot fanboy.”

Pippa York beside a mural dedicated to her in Lennonxtown (credit: Graham Watson)

Pippa York beside a mural dedicated to her in Lennonxtown (credit: Graham Watson)

A lot has changed in the past three decades for Pippa York. She admits that, during her career, she was “five per cent happy” living as Robert Millar, a contentedness rating which has since been boosted to 95 per cent following her transition.

Her relationship with Walsh, once a cold, practically non-existent stand-off between a reticent, single-minded bike racer and a young, hungry journalist fed up with one-line answers, has also changed, evolving into a genuine friendship carved into being on France’s roads.

But has cycling changed much in the past 30 years? York isn’t so sure.

Criticising what she regards as the overt focus placed on trans athletes by sporting governing bodies and their “third-rate failed politicians” – “What’s the trans world record for the 100 metres? You don’t know,” she asserts – York concludes that “it’s all just about money and influence”.

“We’ve separated sport out of the real world and into this Disneyland, where everything’s perfect. And that’s why we’re all so annoyed about doping and cheating, and all these characteristics that exist everywhere else, but that are not allowed to exist in sport.

“If you look at cycling, what has really changed? There was a big change with the arrival of Lance Armstrong, and the Americans, and that money system. But what’s really changed with the politics, and the distribution of wealth and resources in cycling? Nothing, nothing’s changed.

“Everything that has happened lately with the rise of women’s cycling has been a struggle and a fight. It’s been a constant reminder that they’re classed as second-class citizens, that it can’t exist in its own right, it has to exist alongside a men’s race.

“For those in charge, change is difficult – it’s a transition they don’t want to take.”

The road.cc Podcast is available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Amazon Music, and if you have an Alexa you can just tell it to play the road.cc Podcast. It’s also embedded further up the page, so you can just press play.