After the European championships it’s plainly clear: Tadej Pogačar is in a league of his own and no one knows what to do about it.

Pogačar is in a league of his own lately. (Photo: Bernard Papon – Pool/Getty Images)

Updated October 8, 2025 09:16AM

Tadej Pogačar has taken the traditional road cycling script and thrown it out the window. All of the tactical plans that you could think of are now useless.

Satellite riders, strong leadouts, big breakaways, and mountain trains – nothing works against Pogačar.

Belgium tried in this past weekend’s European championships, they really did. Their tactics weren’t perfect, but I’m not sure that would have changed the outcome of the race.

The team around Remco Evenepoel opened the race early, first with 109km to go, and then again at 92km to go. They went on the attack, paced hard, threw riders in the breakaway, and isolated Pogačar with a long way to go.

But in the end, the race still came down to a 1v1 between Pogačar and Evenepoel, and it was the world champion who came out on top. Evenpoel tried to chase, but even with the help of a few others, the Belgian couldn’t close the gap.

Pogačar has dominated so many races this season, as he has in years past. But this time, it feels different.

His attack is inevitable, but no one can do anything about it. The strongest teams in the world can put their entire squad into rotation, but they still cannot bring back Pogačar.

So we’ve arrived at the million-dollar question: How does Pogačar do it? How can he win solo by attacking 60-100 kilometers from the finish? And when everyone knows it’s coming, why can’t they do anything to stop it?

First, let’s take a detailed look at the European championships, and then we’ll attempt to answer those key questions.

Pogačar’s unstoppable solo at the Euro championships

Pogačar rode everyone off his wheel — again. (Photo: Billy Ceusters/Getty Images)

Pogačar rode everyone off his wheel — again. (Photo: Billy Ceusters/Getty Images)

The 202km Euros road race was a perfect route for Pogačar. It included 3400 meters of climbing across 13 categorized ascents. The long climbs came in the first half of the profile while the second half included multiple repetitions of the short and steep Val D’Enfer (1.6km at 9.7%).

Pogačar had multiple attacking options: go on the long climb of Saint Romain de Lerps (7km at 7.2%), or wait for the steep reps of the Val D’Enfer. But in the end, he wasn’t the first contender to make a move.

Belgium attacked with 109km to go, dropping Jonas Vingegaard and a host of other riders from the main group. Pogačar wasn’t bothered, but his Slovenian teammates were, many of them dropping for good at this point in the race.

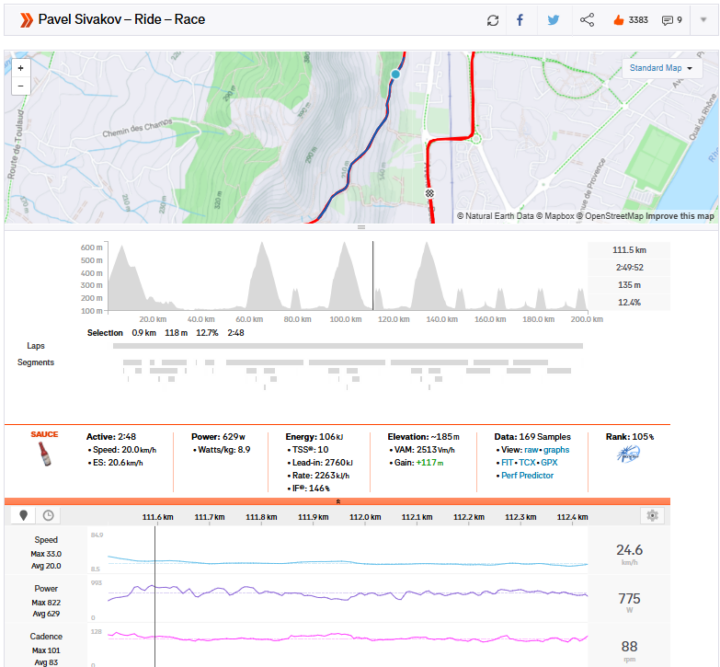

The next major attack came on the Val d’Enfer with 92km to go. They hadn’t even reached the shorter circuits yet, but that didn’t stop Jan Christen, Pavel Sivakov, and Evenepoel from making a major move. This was an all-out effort for nearly every rider in the race, as we can see from Sivakov’s Strava file. The Frenchman rode on the wheels of Pogačar and Evenepoel for most of the climb, even as the group split completely behind.

This effort on its own is ridiculously hard. Most WorldTour pros couldn’t match this power in a fresh effort, let alone in the middle of a 202km race.

Pogačar and Evenepoel – Val D’Enfer with 92km to go

Time: 2:48

Estimated Power: ~9w/kg

VAM: 2,525 Vm/h

Sivakov: 629w (8.9w/kg) for 2:50 at 2,513 Vm/h

2,500 Vm/h is so incredibly fast that it’s hard to put it into words. Most amateurs could maintain that climbing speed by sprinting up a 30-second hill. To hold it for three minutes and then continue racing 92km is out of this world. And that’s exactly what these riders did.

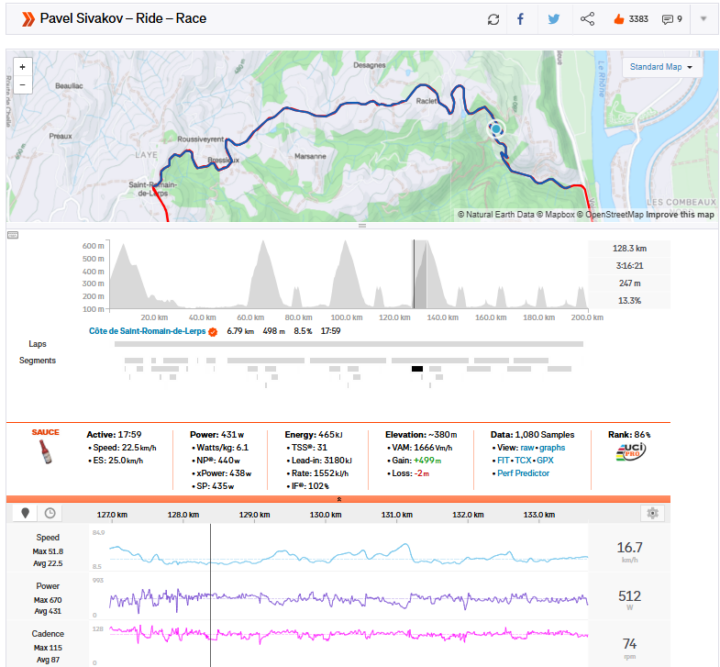

After catching the early breakaway, Belgium led into the final climb of the Saint Romain de Lerps with 77km to go. Pogačar attacked 1km later, immediately dropping everyone but Evenepoel. The Belgian held on for a few minutes before exploding on the uphill slopes and fading back to the chase group. With 73km to go, Pogačar was solo and never to be caught. That was it.

When looking at Sivakov’s file, we can see that the first part of the Saint Romain de Lerps was paced at ~7w/kg. Then, Pogačar attacked, with only Evenepoel able to follow. Sivakov was not only dropped, he also imploded on the climb, fading to under 5.8w/kg for the final few minutes of the effort. A rider at this level had an FTP higher than 6w/kg – and Sivakov was barely able to hold upper Zone 4 power.

Pogačar – Saint Romain de Lerps with 77km to go

Time: 16:18

Estimated Power: ~7.2w/kg

VAM: 1,838 Vm/h

Sivakov: 431w (6.1w/kg) for 17:59 at 1,666 Vm/h

The chase group was Evenepoel, Paul Seixas, Christian Scaroni, and Juan Ayuso. Evenepoel did the lion’s share of the work, while the others tried to contribute. But the Belgian was clearly the strongest, and he eventually made his way into second place behind Pogačar.

In the end, the time gaps were absolutely massive. The double World Champion relaxed enough that Evenepoel finished within a minute, but Seixas took third at 3:41 down on Pogačar. 10th place was nearly seven minutes behind Pogačar, and there were only 17 finishers. Pogačar had not only destroyed the field, he had forced them into agony.

It seems like Pogačar has cracked the code and that no one can stop him.

Why can’t anyone stop Pogačar’s solo attacks?

Evenepoel put up a brave fight but couldn’t close the gap. (Photo: Bernard Papon – Pool/Getty Images)

Evenepoel put up a brave fight but couldn’t close the gap. (Photo: Bernard Papon – Pool/Getty Images)

There is good news for everyone in the pro peloton not named Tadej Pogačar: you can still beat him. It is possible. It happened at this year’s Amstel Gold Race, and it can happen again.

But here is the reason that Pogačar’s attacks work so well: he attacks so hard that everyone goes into the red trying to follow. And they don’t just go into the red, they go so far over their limit that they can never recover. Pogačar’s attacks are so ridiculously fast that anyone within 10 seconds of him is guaranteed to blow up. Just look at Juan Ayuso and Isaac Del Toro at the world championships in Rwanda. Or Vingegaard at the Tour de France. Or Evenepoel in this very race.

Pogačar’s attacks work so well because everyone chasing him is absolutely exhausted, and no one wants to commit. We could see this scenario play out at Tre Valli Varesine where Pogačar, again, won solo. The chase group was strong, but only a few riders were somewhat committed to the chase. As soon as that happens, the race is over.

At the world championships, how many kilometers did it take for Italy and France to organize their chase? Too long. By the time they finally got going, Pogačar’s gap was unbridgeable, and the riders behind were too tired.

The only race this year where Pogačar’s solo attack didn’t work was the Amstel Gold Race. Of course, he didn’t win Milano-Sanremo or Paris-Roubaix, but he was never solo in those races. So let’s zoom in on this unique effort.

The Amstel Gold Race is made for Pogačar. It is very long, very hard, and extremely difficult to win. On a parcours this difficult, it is typically the strongest rider that comes out on top. So when Pogačar went solo in this year’s edition, we all thought that the race was over. But some interesting things were happening behind.

Mattias Skjelmose had broken away from the chase group, and then Evenpoel came across with 25km to go. Neither rider was willing to settle for a podium, so they pulled with everything that they had. They did not skip turns or feign fatigue.

Pogačar had a 30-second lead, like he has in so many races this year. It is not a bridgeable gap, one that can be closed with a single explosive effort. Instead, it’s a gap that requires patience and persistence to close. Evenepoel and Skjelmose worked together for 17km before they finally caught Pogačar – that’s the kind of commitment it takes to close just a half-minute’s lead.

After five hours and 50 minutes of racing, Pogačar was defeated, beaten by Skjelmose in the sprint. And that is how you beat Tadej Pogačar. Let’s break it down a bit further. If you are trying to beat Pogačar, this is what you need to know.

He is going to eat your right hooks and counter you with a devastating uppercut. The “fatigue” that you are trying to put into his legs…that doesn’t work. His FTP is nearly 7w/kg. That means all of his zones (i.e. Zone 2 endurance, Zone 3 tempo, Zone 4 threshold, etc.) are 50-100w higher than yours. If you are riding in Zone 4 on a climb, he is riding in Zone 3. Everything that you do, he can do better – he is nose breathing as you start to gasp for air.

You know that his attack is coming. It’s inevitable, so you need to be prepared for it. Don’t try to follow like Evenepoel in Euros or Del Toro in worlds – just look at how that turned out for them. Even if you can follow for a bit, you will soon implode. Don’t make that mistake. Instead, control your effort and go as fast as you can behind Pogačar.

Ideally, you get into a group of like-minded riders. Think Healy and Skjelmose at the world championships. Now you have a group of strong riders only 30 seconds behind Pogačar, all willing to work together to close the gap. When you close the gap, Pogačar will finally be tired (even more tired than you) because he has been riding solo, whereas you have been in a group. That’s when you finally have a chance to beat him.

He needs to be more fatigued than you are.

With that, you have a chance.

At the European championships, Evenepoel, Ayuso, Seixas, and Scaroni were too tired by the time they organized their chase. You could tell by their body language and unwillingness to work. The drooped heads, flailing elbows, and negative posture. They were all defeated, despite there being more than 70km to go.

Contrast that with Healy at the world championships. He looked like a man on a mission, a rider in control of his effort. Willing to ride as hard as he could for the best possible result. Del Toro went too hard too early, and he certainly paid the price. We’ve seen it over and over again, and history could repeat itself at Il Lombardia. We’ll see if a small group of riders can organize a chase because it is only a matter of time before Pogačar goes solo.

Power Analysis data courtesy of Strava