Rape and revenge movies are inherently muddled in their ideology, eroticizing every assault while pretending that the subsequent bloodletting stands as an unambiguously pro-woman stance. But Ms. 45 expressly foregrounds its thematic confusion. Abel Ferrara’s 1981 exploitation thriller isn’t about justified comeuppance, but rather the mental collapse of a deeply traumatized individual, whose actions are merely a perpetuation of senseless violence.

Rape and revenge movies are inherently muddled in their ideology, eroticizing every assault while pretending that the subsequent bloodletting stands as an unambiguously pro-woman stance. But Ms. 45 expressly foregrounds its thematic confusion. Abel Ferrara’s 1981 exploitation thriller isn’t about justified comeuppance, but rather the mental collapse of a deeply traumatized individual, whose actions are merely a perpetuation of senseless violence.

To even call Ms. 45 a revenge film is to miss how quickly mute garment worker Thana (Zoë Lund) gets back at her attacker. Or one of them, at any rate. The film begins with Thana coming home after work, being raped in an alley, then arriving home only to surprise a burglar, who also rapes her until she fights back and caves in the man’s head with an iron.

For the remainder of the film, Thana targets men who fit various chauvinistic archetypes but don’t scan as grotesque caricatures. Scenes depicting an abusive pimp and gangbangers getting theirs blend with no discernible order with Thana’s less righteous attacks, like that of a catcalling loser who follows her in order to return the bag of victims’ clothes she deliberately drops. Most everyone is overdue for at least a dressing down, if not a harassment suit or even some jail time, but no sense of vicarious justice comes from Thana’s spree.

With porcelain skin and lips you could spot two boroughs over, the then-teenaged Lund looks like she walked out of an exploitation producer’s perverted dreams, yet even performing in her first movie, she projects such intensity and command of expression that when Thana unloads a clip into some poor bastard, it’s hard not pay attention to anything but her face.

On paper, Thana comes off as a collection of signifiers, from her name (reminiscent of Thanatos, the Greek god of death) to her muteness as a physical manifestation of the passive and sometimes active silencing of abused women. As Lund plays her, though, Thana is as terrifying as she is believable in her extremity, and every bit as much as the bit players and extras who appear across the film, which at times scans as a documentary of pre-gentrification New York City. Even when she shows up for a final massacre wearing an eroticized nun’s habit, Thana blows right past symbolism to be simply, inescapably present.

Ms. 45 also represents a notable artistic leap forward for Ferrara following The Driller Killer. He often takes sophisticated direction to the proceedings, as in the high-angle establishing shot of the killing of the gangsters who follow Thana, with the men arranged in a star pattern around her. It’s a moment that may leave you believing that you’re watching a spaghetti western.

Ferrara’s camera is as crucial to giving voice to Thana’s interiority as Lund. Ms. 45 announces its artistic and thematic ambitions even in the rape scenes, in which the camera not only skirts gratuitous nudity, but remains fixated on Lund’s face as she contorts in silent screams and, finally, as her eyes go slack, transporting herself to some far-off place where no harm can come to her. Elsewhere, close-ups spiked with Joe Delia’s score of street-scuffed disco, funk, and jazz orient even innocent interactions around Thana’s caged-animal response, and the slow motion of the climax emanates as much from her sense of purpose as the bystanders’ frozen terror.

Ms. 45 offers an early glimpse of the postmodern guttersnipe effrontery behind Dangerous Game, New Rose Hotel, and Go Go Tales. Whether done to keep costs down or out of conscious awareness of its implications, Ferrara’s decision to cast himself as the first rapist acts as a skeleton key for an entire career predicated on the unavoidable exploitation of filmmaking. As he leaves Thana in a pile of garbage, Ferrara’s rapist hisses, “I’ll see you later, baby,” and as every man but him meets a grim fate, the clear inference is that he’s escaped to behind the camera. That adds even more charge to those frantic close-ups of Thana’s tensing face, and the shots of her pointing her Colt just off screen suggest that she can sense the one that got away.

Image/Sound

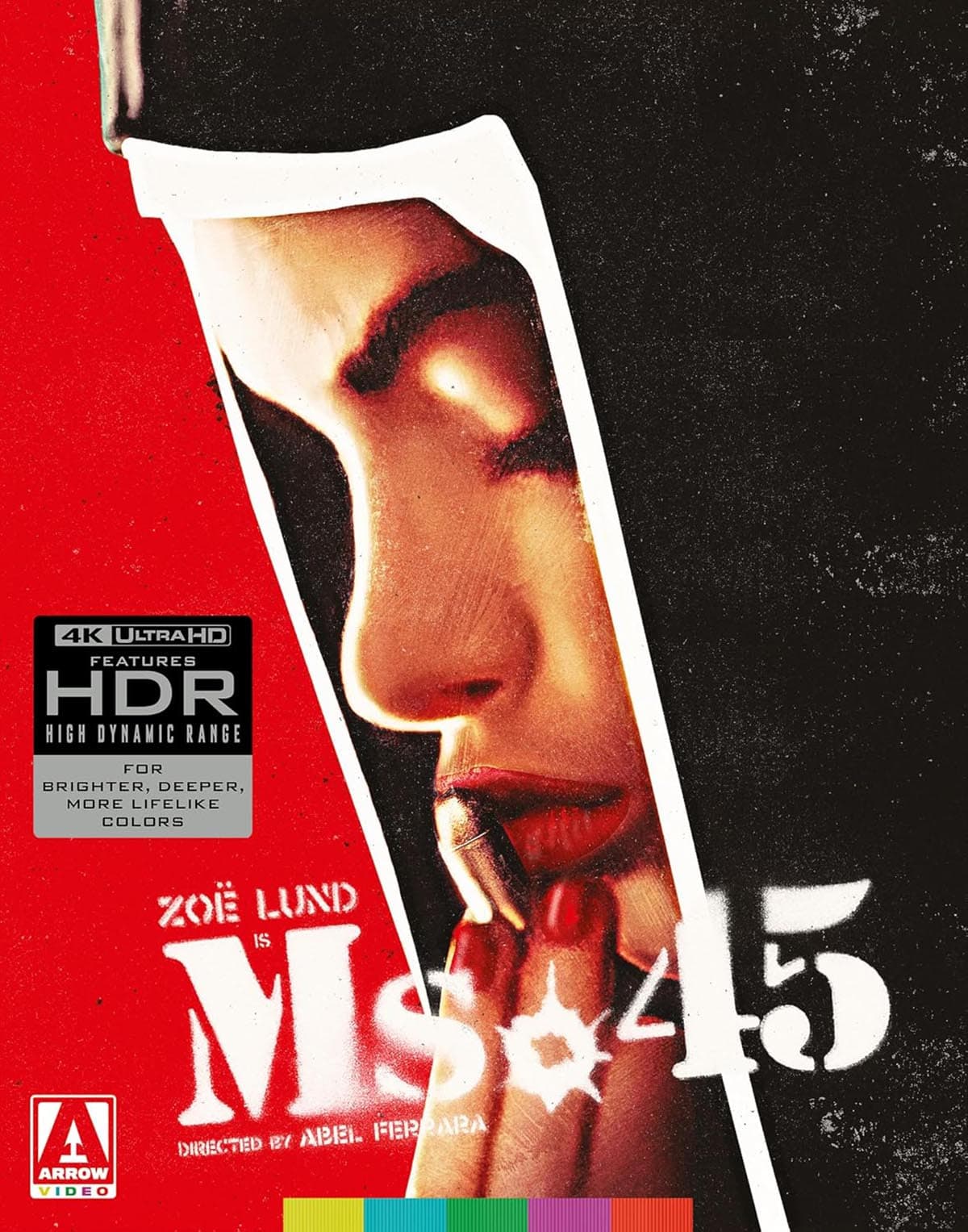

Shot on 35mm, the film often has the thick grain and faint color bleed more common to 16mm, and that slight softness is reflected on this release. Nonetheless, Arrow Video’s transfer does offer a clear upgrade in color depth and texture over the presentation on the 2014 Blu-ray by Drafthouse Films. The smeared reds that dominate the palette glow more intensely, while the griminess of Koch-era New York streets and poorly kept apartments is more viscerally felt. The soundtrack shows no appreciable difference from the one on Drafthouse’s disc, the mono mix ably separating out Foley effects from Joe Delia’s half-sleazy, half-tense score.

Extras

Arrow’s release comes with the same extras that adorned Drafthouse’s disc. Interviews with Abel Ferrara, Delia, and production designer Jack McIntyre abound in insights about the film’s making, and two shorts by Paul Rachman about Zoë Lund—who died in 1999 from heart failure, caused by extreme drug use—one with contributions from her husband and one from her mother, are sad, abstract, intensely subjective tributes to her short life.

Additionally, the disc includes some newly commissioned extras, starting with a commentary by critic and author Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, who situates Ms. 45 in the tradition of rape-revenge movies and calls attention to Ferrara’s grappling with contradictions, and in artful ways, that make it impossible to dismiss the film as a slice of z-grade exploitation cinema.

A video essay by critic BJ Colangelo is a detailed look at Ferrara’s direction and Lund’s performance, highlighting small choices that are easy to miss among broader gestures like Ferrara’s depiction of violence or Lund’s miming expressions. And in a second video essay, critic Kat Ellinger discusses the film as one of the great snapshots of New York City in its punk and no-wave era as a microcosm of larger American decline.

An accompanying booklet contains a new essay by Lund’s husband, Robert, who offers a miniature biography of his late wife and how her character in the film eerily mirrored traumas from her own life. Arrow also reproduce the writings from Drafthouse’s own disc booklet: a 1992 “biographical sketch” by Zoë Lund, as well as critical essays by Kier-La Janisse and Brad Stevens that provide overviews of the film and the careers of Ferrara and his lead actress.

Overall

Abel Ferrara’s first great film receives a definitive home-video release from Arrow Video.

Score:

Cast: Zoë Lund, Steven Singer, Jack Thibeau, Peter Yellen, Abel Ferrara Director: Abel Ferrara Screenwriter: Nicholas St. John Distributor: Arrow Video Running Time: 80 min Rating: R Year: 1981 Release Date: October 28, 2025 Buy: Video

If you can, please consider supporting Slant Magazine.

Since 2001, we’ve brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.