As late stars go, nobody is more beloved than David Bowie. Who else gets their entire archive bequeathed to the V&A, now available to the public at the recently opened David Bowie Centre in east London? Yet like a surprisingly large number of rock’s most complex and creative figures, Bowie flirted with some extremely dangerous ideas.

In August 1975 Bowie, having created his Thin White Duke persona as, in his words, “a very Aryan, fascist type”, called for “an extreme right front [to] sweep everything off its feet and tidy everything up”. The next year he told Playboy magazine that “Adolf Hitler was one of the first rock stars” and was photographed in London giving what looked like a Nazi salute from the back of an open-top Mercedes (Bowie claimed he was simply waving to fans).

Was Bowie a Nazi? Of course not. But a combination of cocaine paranoia, isolation, the ego-distorting effects of fame and, as he said in an apologetic interview in 1993, “my extraordinarily f***ed-up nature at the time”, led to a preoccupation with the most murderous political ideology of the 20th century. Now, at a time when rising antisemitism has been highlighted by the Manchester synagogue attack, one author has dug deep into rock and pop’s enduring obsession with Nazism.

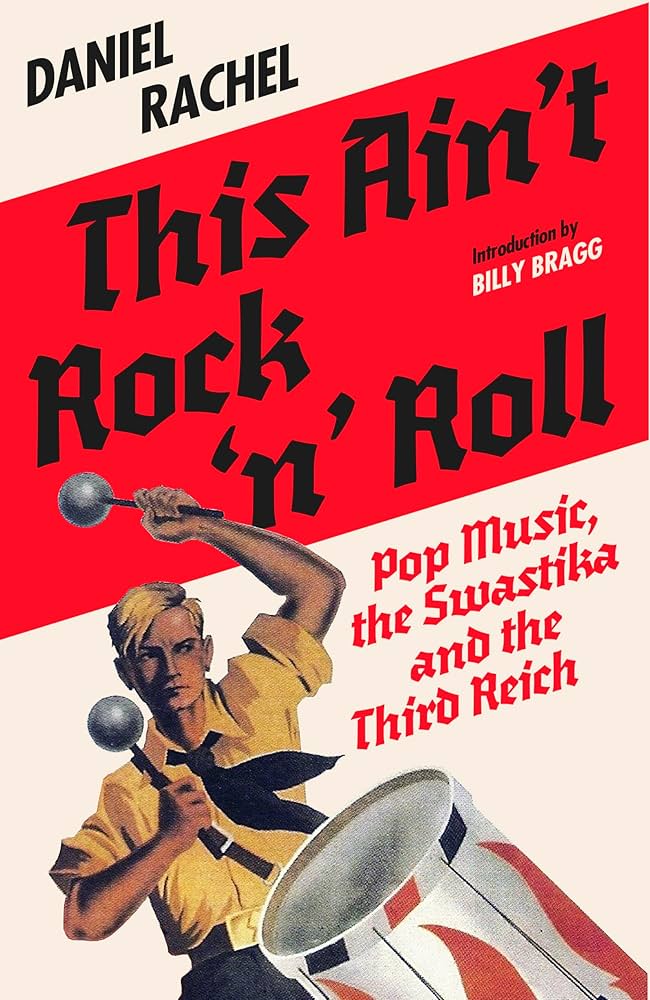

“It felt important to collate pop music’s history with the swastika and the Third Reich,” says Daniel Rachel, the author of This Ain’t Rock ’n’ Roll. He has written books about Britain’s two-tone movement (Too Much Too Young) and Rock Against Racism (Walls Come Tumbling Down), making this one a companion piece to his accounts of British pop’s most significant anti-racist movements. “There are personal reasons too,” he adds, “which go back to my childhood.”

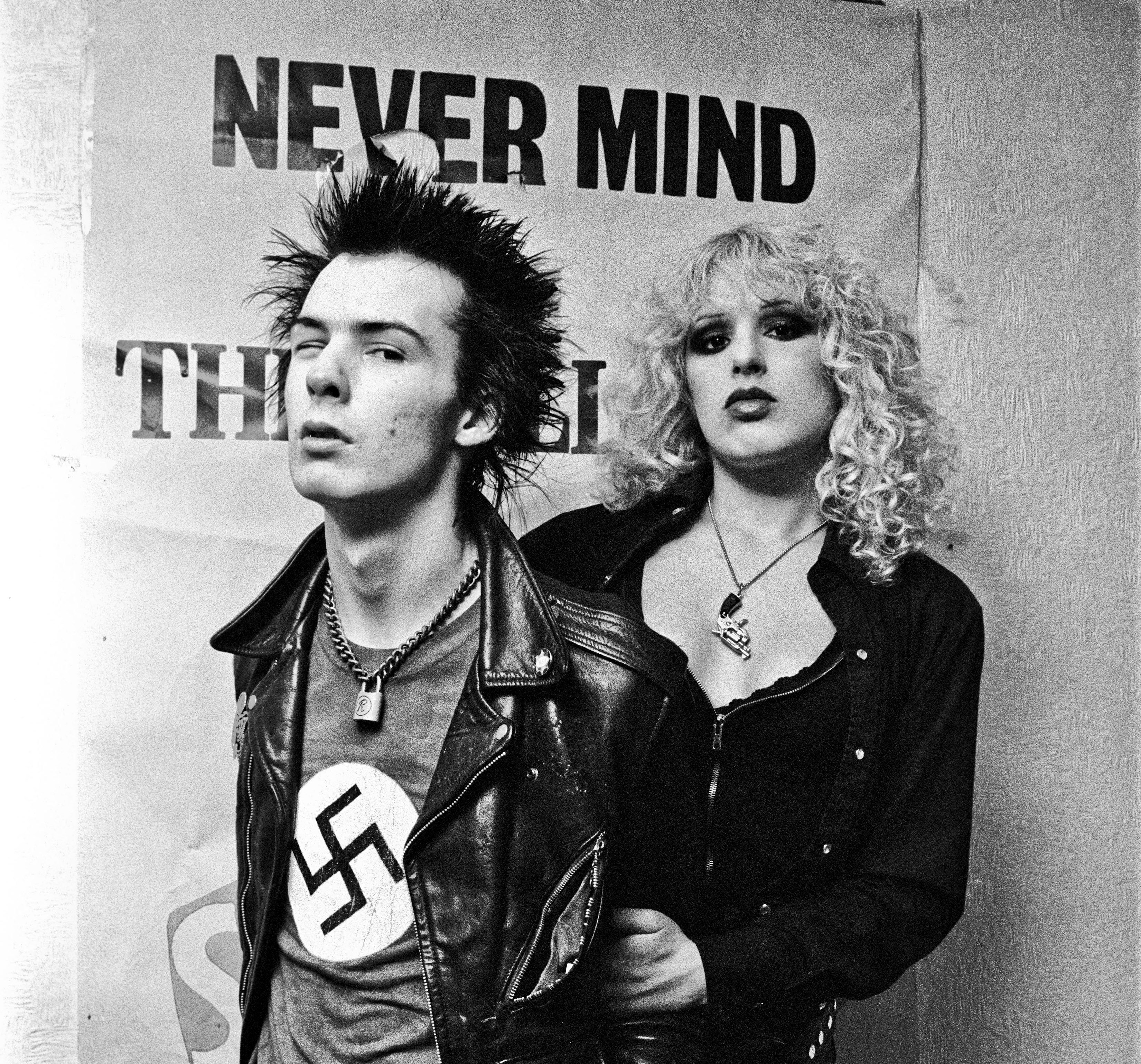

Rachel grew up in Birmingham in the 1980s and, like many children of his generation, fell in love with the Sex Pistols. “I would happily sing along to Belsen Was a Gas,” he says, citing the punk pioneers’ most gratuitously tasteless song. “I saw images of Sid Vicious with a swastika armband and thought it was funny. At the same time, raised in a Jewish house, I began to understand what the Holocaust was, and to see images of mass burial sites at Belsen while singing Belsen Was a Gas triggered an emotion that was difficult to unravel. It has stayed with me ever since.”

Sid Vicious from the Sex Pistols in a swastika T-shirt, with his girlfriend Nancy Spungen, 1978.

CAMERA PRESS

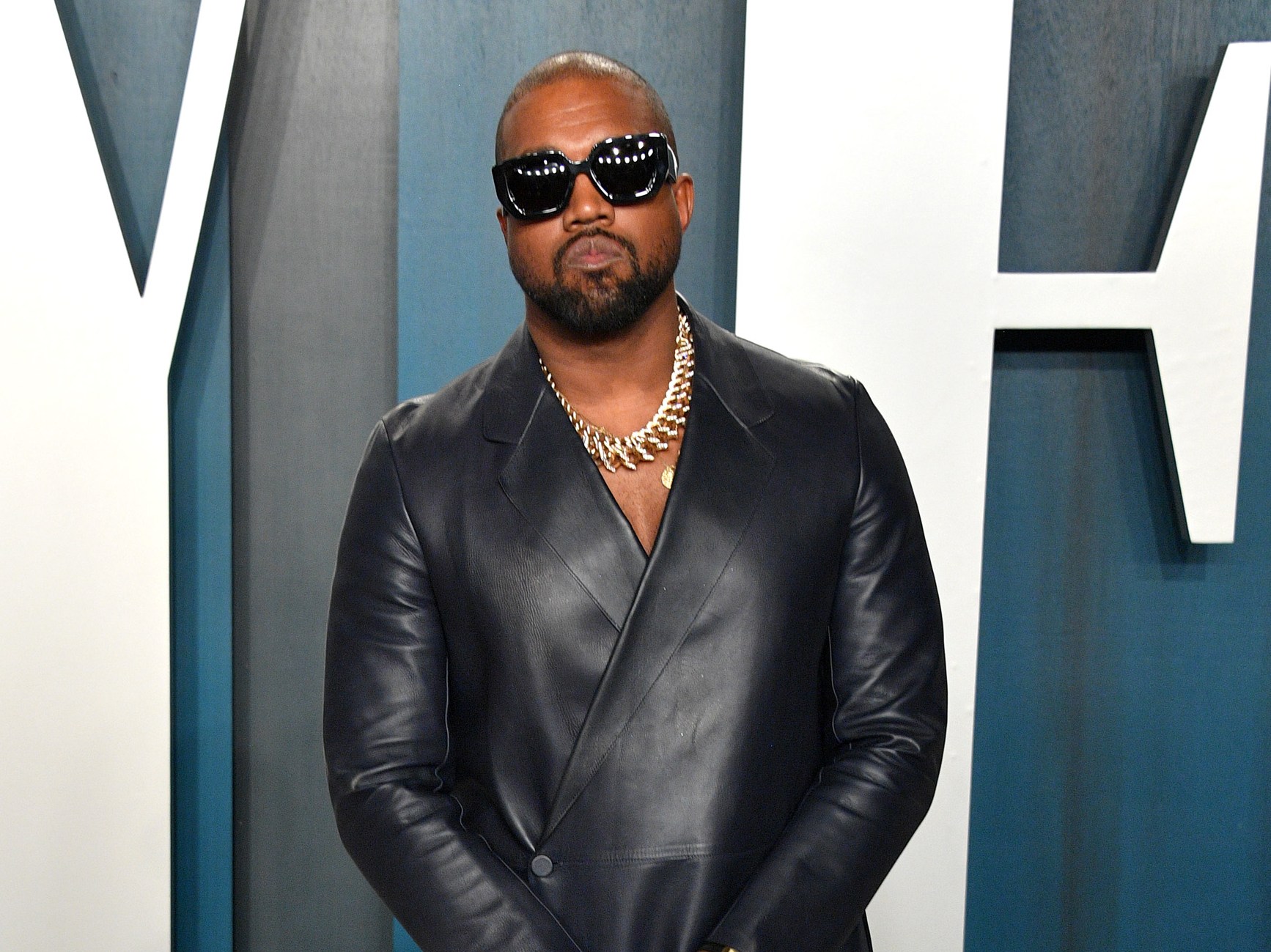

It is remarkable just how many rock and pop stars have toyed with Nazism. Sometimes it has been calculated to offend — as when Keith Moon of the Who and Vivian Stanshall of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band dressed up as Nazis and paraded through the Jewish north London neighbourhood of Golders Green in 1970 before being chased by a woman from a kosher bakery. Sometimes it has been a sign of mental disintegration, such as the rapper Kanye West selling swastika T-shirts on his website. In all cases it has not aged well.

“I don’t want to be the Simon Wiesenthal of rock’n’roll,” Rachel says, referring to the Austrian Holocaust survivor and Nazi hunter. “But it’s happening in plain sight and being digested by, in some cases, millions of people. Having laid all this out in the book, I’m asking, why is this still going on?”

• Caitlin Moran: Selling Nazi T-shirts at the Super Bowl? Even for Kanye, it’s a new low

There are some surprising people among the roll call. John Lennon had a collection of Nazi memorabilia, and among his ink drawings was a self-portrait with a Nazi salute and the words “Heil John”. He kept both private. “We only know about them because they were sold after [his first wife] Cynthia Lennon’s death,” Rachel says. “Lennon’s experience reflects that of many people who were born into the war. British men before them had to kill Germans, and then the Beatles were playing in front of German audiences. On his first trip to the US John was deeply shocked to see a swastika on an elevator wall — so I don’t want to kick on John Lennon but [Lennon’s interest in Nazism] was a starting gun in rock’n’roll history.”

In 2023 Rachel visited concentration camps in Poland, where he found SS membership cards and swastika armbands in antiques shops. “I found myself almost wanting to buy them, to hold these relics associated with mass murder, so I do understand [the fascination],” he says. “But Keith Moon parading around Golders Green in an SS uniform only 20 years after the Holocaust? That can’t be right.”

Does he think it was stupidity or provocation? “Both, and they are the substance of rock’n’roll. I was in a band for most of my younger years and not thinking about what you’re doing is a mainstay of band life. But that’s why the infrastructure around it has to take responsibility.”

Ignorance can also play a part. Holocaust history was not compulsory in British schools until 1991, while in the US it is compulsory in only 27 states to this day. “[The Holocaust] was an orchestrated genocide,” Rachel says. “That understanding wasn’t necessarily present in the history of rock’n’roll but it should be now.”

• How Myra Hess defied the Nazi bombs to bring music to wartime London

How about Bowie, who certainly wasn’t ignorant of war history? “You’re dealing with someone who planned to write a musical about Goebbels, and that can’t all be excused away by cocaine use,” Rachel says. “Bowie, Mick Jagger and Bryan Ferry have talked about the impact of Leni Riefenstahl’s film of the Nuremberg Rallies, and when you watch Triumph of the Will it’s easy to see a parallel with Hitler doing a Sieg Heil before thousands of people and a rock star on the lip of a stadium stage, controlling an audience. But in rock’n’roll there has been an attempt to divorce the spectacle [of Nazism] from the reality, which was an attempt to exterminate the Jewish people. These musicians are divorcing theatre from mass murder.”

What about musicians who claim they are keeping alive the memory of Nazi atrocities so that they don’t happen again — as the 1970s art rock shockers Throbbing Gristle did when they used imagery of Nazi death camps? “I’m hugely sceptical of people who say they dress up in a Nazi uniform so people don’t forget,” Rachel says. “The scariest thing about Throbbing Gristle is that when you go down the staircase of Rough Trade on Denmark Street [a shop in central London], you’re confronted by a Throbbing Gristle poster of the gas chamber at Auschwitz and the words, ‘Music from the Death Camp’. What am I meant to think of that?”

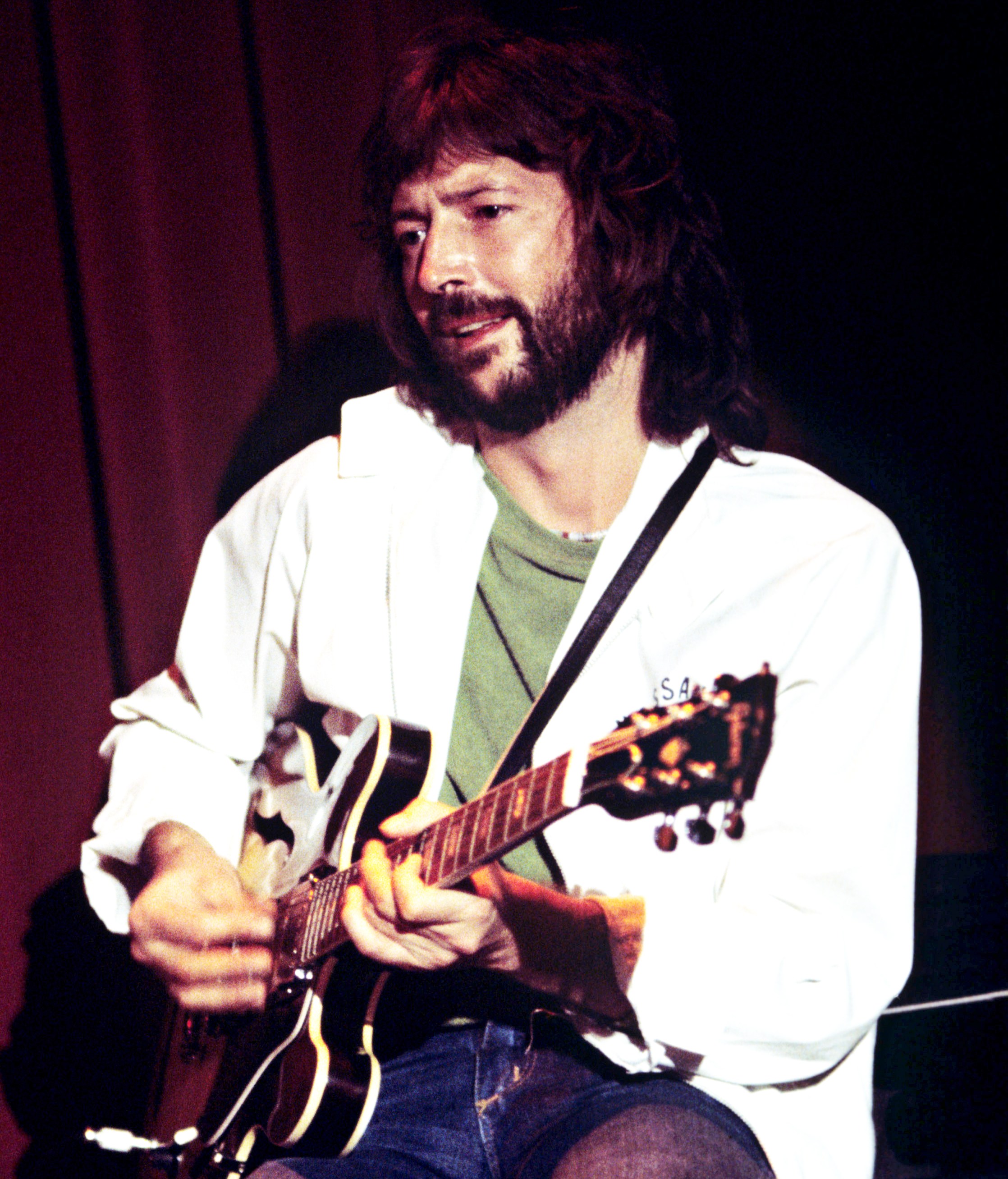

Eric Clapton in 1976, the year his Birmingham Odeon concert kickstarted the Rock Against Racism movement

ARMANDO GALLO/GETTRY IMAGES

As Rachel points out, a poster showing people being lynched or raped would be unthinkable in a record shop. “We treat racism and misogyny seriously in rock’n’roll now,” he says. “It has become accountable, which is why Mick Jagger no longer includes Brown Sugar in Rolling Stones sets. So why is Nazism exempt?”

Indeed, one of the most famous examples of racism in rock inspired an entire movement. “Do we have any foreigners in the audience tonight?” Eric Clapton asked at an August 1976 concert at the Birmingham Odeon, not far from where Enoch Powell had made his “Rivers of Blood” speech in 1968. “Stop Britain from becoming a black colony. Get the foreigners out,” he continued. A left-wing activist called Red Saunders wrote to NME in protest, and Rock Against Racism was born.

One of the strangest episodes is punk rock. The Sex Pistols’ manager, Malcolm McLaren, who was brought up in a Jewish community in Stoke Newington, gave the band swastika armbands to wear. Siouxsie Sioux of Siouxsie and the Banshees, influenced by The Night Porter, an erotic 1974 film about a sadomasochistic relationship between Dirk Bogarde’s former concentration camp officer and Charlotte Rampling’s former inmate, wore a swastika armband at early concerts. The original version of the Banshees song Love in a Void featured the line: “Too many Jews for my liking.” Why?

Bowie starred as an aristocratic Prussian officer in the 1978 film Just a Gigolo

ALAMY

“Where were the people, from then until now, posing that question?” Rachel asks. “In the early Nineties Malcolm McLaren trotted out some vacuous excuses about shock value. But the counter to McLaren was the Clash’s manager, Bernie Rhodes, who had Holocaust survivors in his family and refused to indulge in it.”

In a 1977 interview in Sounds magazine with the Jewish writer Vivien Goldman the Banshees dismissed the accusation that Love in a Void was antisemitic, claiming the offending line referred to “too many businessmen”. “But what is that saying?” Rachel asks. “None of it makes sense, to be honest.”

• Revealed: David Bowie’s secret list of his favourite songs

While writing the book, Rachel approached musicians who had used Nazi imagery. “There was a perhaps understandable silence from those with compromised pasts,” he says of the response. “So it became more important to examine justifications from the time.” These ranged from annoying an older generation (“It was an anti-mum-and-dads thing” said Siouxsie Sioux) and extreme dysfunction (Bowie’s drug use) to protestations of ignorance. “Never did any of us consider a certain Mr Hitler,” claimed Peter Hook of New Order (a band named after the name Hitler gave to his vision of an Aryan Europe), previously of Joy Division (named after the name given to Nazi brothels).

Not everyone, however, simply took Nazi imagery and ran with it. “Serge Gainsbourg made a whole album called Rock Around the Bunker,” says Rachel, citing the great French songwriter’s 1975 record about Hitler’s final moments, which he wrote as an attempt to “exorcise the period I lived in when I was a kid, when I was marked with a yellow star”. “The proud tradition of rock’n’roll is of standing up to injustice,” Rachel says. “Paul Weller did it with elegance and beauty on Ghosts of Dachau, as did Leonard Cohen on Dance Me to the End of Love.”

I wonder how Rachel’s relationship with Bowie, the Sex Pistols and countless others has been tainted by his research. “It was a really hard book to write for that reason,” he says. “I love many of these artists’ music and I don’t want to be denigrating people who have meant so much to me. But the book asks: how much longer can we separate the art from the ideas? I’m not saying we stamp on our record collections but that we need to move forward.”

Kanye West has praised Hitler, denied the Holocaust and self-identified as a Nazi

GEORGE PIMENTEL/GETTY IMAGES

Sometimes we seem to be moving backwards. In 2023 Chaeyoung of the Korean girl group Twice posted a picture of herself wearing a T-shirt showing Sid Vicious and a swastika. In the tightly controlled world of K-pop, which comes from a country that was under Japanese colonial rule until the end of the Second World War, did nobody think this was a bad idea? Kanye West, once a hugely innovative figure, has in recent years praised Hitler, denied the Holocaust and self-identified as a Nazi. Even taking into account his poor mental health, supporting West looks like collusion — yet a million people bought his last album. Rock’n’roll has always given its heroes the right to behave outside societal norms but there has to be some kind of accountability.

“The last song I heard by Kanye West has the chorus ‘Heil Hitler,’” Rachel says. “Who were the engineers, who was the manager, who is buying it? We can’t just single out the artist.”

Ultimately flirtation with Nazi imagery cannot be divorced from the realities of Nazi ideology and what it led to. “I can see parallels with the rise of the Nazi party in the early Thirties and what has been happening in America under Donald Trump — a belief that democracy isn’t working,” Rachel says. “The next step is to find scapegoats, so the stronger the defensive wall within rock’n’roll, the better.”

Let’s hope rock’n’roll, which after all built itself on the power of rebellion and the ability to speak truth to power, steps up to the challenge.

‘Rock stars are fascists’: David Bowie and the dark side of the Thin White Duke, by Daniel Rachel

In 1969 David Bowie made a prophecy. “This country is crying out for a leader,” he told Music Now! magazine. “God knows what it is looking for, but if it’s not careful it’s going to end up with a Hitler.” Over the next few years he released a series of songs exploring the ideas of fascism: The Supermen from the album The Man Who Sold the World (1970); the call to “make way for the homo superior” in the lyrics to Oh! You Pretty Things (1971); and “Himmler’s sacred realm of dream reality” in Quicksand (1971).

This paved the way for Bowie’s Thin White Duke — emaciated, cocaine-fuelled and infatuated with the Third Reich. For his Diamond Dogs tour in 1974, Bowie gave the set designer Mark Ravitz a three-word brief, “Power, Nuremburg and Metropolis”, adding: “I want tanks, turbines, smokestacks, fluorescent lightning, alleyways, cages, watchtowers, girders, beams, Albert Speer.”

“Everybody was convincing me that I was a messiah, especially on that first American tour [in 1972],” Bowie told Rolling Stone magazine three years later. “I got hopelessly lost in the fantasy. I could have been Hitler in England. Wouldn’t have been hard. Concerts alone got so enormously frightening that even the papers were saying, ‘This ain’t rock music, this is bloody Hitler! Something must be done!’ And they were right. It was awesome. Actually, I wonder,” Bowie added, “I think I might have been a bloody good Hitler. I’d be an excellent dictator. Very eccentric and quite mad.”

• David Bowie unseen: inside his archive of 90,000 personal treasures

“Rock stars are fascists,” Bowie told Playboy magazine in 1976. “Adolf Hitler was one of the first rock stars. Look at some of his films and see how he moved. I think he was quite as good as Jagger. It’s astounding. And boy, when he hit that stage, he worked an audience. Good God!”

On May 2, 1976, returning to England for the first time in two years, Bowie arrived at Victoria station in London and greeted a horde of fans in an open-top Mercedes-600. Standing in the back, with slicked back hair and a black shirt, Bowie waved to a jubilant crowd. The media pounced. The Daily Mail reported that Bowie had saluted the crowd. The NME ran an image of Bowie with an extended right arm and the unforgiving headline, “Heil and Farewell”.

“That photograph caused an awful lot of trouble,” says the man who took it, Chalkie Davies. “The whole thing lasted about 30 seconds. I managed to grab two frames, but, sadly, when I saw the negatives, I realised my image was a little blurry and Bowie’s hand had been reduced to a mere sliver. The NME needed the picture first thing Monday morning but after I’d sent it, the retouchers drew a hand onto his arm. When the image appeared in that week’s edition, he appeared to have raised his hand in salute.”

“My image was blurry and the retouchers drew a hand onto his arm,” says the photographer Chalkie Davies. The NME published it with the headline “Heil and Farewell”, though Bowie always insisted he had only waved

CHALKIE DAVIES/GETTY IMAGES

A 17-year-old Gary Numan — himself on the cusp of stardom, and stylistically indebted to his idol — was in the crowd and adamant that Bowie had innocently gestured. “If a photographer takes a whole motor-driven film of someone doing a wave you will get a Nazi salute at the end. I’d be amazed if he did a Nazi salute. I didn’t see anyone walking around saying, ‘What a wanker, he did a Nazi salute.’ People just thought he was waving, and I’m sure he was.”

In Britain to perform a sold-out six-night residency in Wembley, Bowie told the Daily Express, “I’m astounded anyone could believe it. I have to keep reading it to believe it myself. I don’t stand up in cars waving to people because I think I’m Hitler. I stand up in cars waving to fans … It upsets me. Strong I may be. Arrogant I may be. Sinister I’m not. What I am doing is theatre.”

• The musicians who embraced Nazism, from the Sex Pistols to Kanye West

But 12 months later, the London Evening News reported that Bowie had reiterated his idea that Britain was “ready for a new Hitler”. The Musicians’ Union (MU) had, by then, called for Bowie’s expulsion. “This branch deplores the publicity recently given to the activities and Nazi style gimmickry of a certain artiste and his idea that this country needs a right-wing dictatorship,” blasted the composer Cornelius Cardew, a branch executive member of the MU. A vote resulted in a 12–12 tie. Cardew made a second speech, arguing that “when a musician declares that he is ‘very interested in fascism’ and that ‘Britain could benefit from a fascist leader’ he or she is influencing public opinion through the massive audiences of young people that such pop stars have access to”. The motion passed: 15 to 2.

To curb a backlash, Bowie attempted to set the record straight. “What I said was Britain was ready for another Hitler, which is quite a different thing to saying it needs another Hitler.” Claiming his politics were closer to communism, Bowie told the music newspaper Record Mirror: “I’m half-Jewish.” Not exactly: it turned out that his older half-brother, Terry Burns, was the child of a relationship between his mother and the son of a Jewish furrier, Jack Rosenberg.

• On the trail of David Bowie — and his favourite haunts

In late 1976 Bowie relocated to Berlin, to record new material in a former ballroom used by the Reichsmusikkammer (Reich Music Chamber) for propaganda concerts and SS dance evenings, until it was partly destroyed by Allied bombing in 1943. This was Hansa Studios, overlooking the Wall. In the song China Girl, which he wrote with Iggy Pop in 1976, Bowie’s lyrics spoke of “visions of swastikas” and “plans for everyone”.

He was cast, alongside Marlene Dietrich in her last role, in the film Just a Gigolo as an aristocratic Prussian officer who, on returning to Weimar Germany after the Great War, finds work in a brothel. Bowie’s character becomes embroiled in Berlin’s underworld before being murdered in street-battle crossfire between Nazis and Communists. The British punk fanzine Ripped & Torn published a photograph of Bowie in character, in tuxedo and bow tie, alongside the words, “You could have been so CLASSY … why did you have to be so NAZI?” In 1981, the National Front (NF) claimed Bowie as one of their own: “It was Bowie who horrified the music establishment in the mid-Seventies with his favourable comments about the NF,” wrote Joe Pearce, the editor of Bulldog, the party’s youth magazine. “Bowie, who, on the album Hunky Dory (1971), started the anti-Communist musical tradition which we now see flourishing amidst the new wave of Futurist bands.”

In fact, Bowie told an American interviewer in 1978 that the National Front was not Britain’s remedy, rather, “an answer to an idiot’s dream” and that the Thin White Duke had been a theatrical device “to show what could happen … which unfortunately backfired”.

Years later, in 1993, he addressed his past fascination with Nazism in an interview with Arena magazine. “It was this Arthurian need. This search for a mythological link with God,” he said, referring to the myth that a prewar Nazi delegation travelled to Glastonbury Tor in search of the Holy Grail. “But somewhere along the line, it was perverted by what I was reading and what I was drawn to. And it was nobody’s fault but my own.”

In the same year, Bowie elaborated during an interview with Brett Anderson in the NME. “I wasn’t actually flirting with fascism per se,” Bowie said. “I was up to the neck in magic which was a really horrendous period … The irony is that I really didn’t see any political implications in my interest in Nazis. My interest in them was the fact that they supposedly came to England before the war to find the Holy Grail at Glastonbury and this whole Arthurian thought was running through my mind. The idea that it was about putting Jews in concentration camps and the complete oppression of different races completely evaded my extraordinarily f***ed-up nature.”

Bowie expressed his past folly from the point of view of a concerned parent. “I didn’t feel the rise of the neo-Nazis until just before I moved out [of Germany in 1979], and then it started to get quite nasty. They were very vocal, very visible. They used to wear these long green coats, crew cuts and march along the streets in Dr Martens. You just crossed the street when you saw them coming. Just before I left, the coffee bar below my apartment was smashed up by Nazis … I thought — this is not a place for [my son] to be growing up. This could get worse.”

This is an edited extract from This Ain’t Rock ’N’ Roll: Pop Music, the Swastika and the Third Reich by Daniel Rachel, published by White Rabbit on Nov 6. To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk. Free UK standard P&P on orders over £25. Special discount available for Times+ members