One of my first features for this newspaper concerned Richard Austin, a Jamaican and West Indies cricketer of mercurial ability. A talented all-round sportsman in his day, Austin played various sports nationally and cricket for the region at a time of immense strength. Yet on my second tour to the Caribbean as a player, he was living in a car park opposite the Hilton hotel in downtown Kingston.

While England were staying in Kingston for a tour match, he had come into the lobby one day looking for a handout. I had seen Austin play league cricket in Lancashire as a boy and was shocked at the transformation from sportsman to dishevelled beggar. It is every athlete’s worst fear, seeing a fellow cricketer so down on his luck that he couldn’t afford shoes or his next meal. What had happened?

What had happened, with cruel irony, is that he had come into some money — specifically by going on one of the rebel tours to South Africa in the early 1980s. At a time when the opportunities for cricketers just below top rank were non-existent and you had to be world class to get into the West Indies team, some on the fringes found the temptation to take the South African rand too strong.

Julien signs autographs during a one-day international against South Africa in Durban during the 1982-83 rebel tour

ADRIAN MURRELL/GETTY IMAGES

While England cricketers who went to South Africa in the early and late 1980s were hit with short-term bans and often quickly rehabilitated, reaction in the Caribbean to black cricketers agreeing to tour apartheid South Africa was, understandably, visceral. Lifetime bans from international and domestic first-class cricket were handed down immediately and public forgiveness was not granted.

A reminder of this story arrived last week with the death of Bernard Julien, the former Trinidad all-rounder, aged 75, whose career ended with the second of those rebel tours. Those of a certain age may remember him playing for Kent, at a time when West Indian representation in the county game was strong. Before the rebel tours, he played for West Indies in 12 ODIs and 24 Tests, making a swift hundred at Lord’s in his third Test in 1973 — a match in which the incomparable Garfield Sobers also scored a century.

He played in the inaugural 1975 World Cup final, when West Indies beat Australia, but flattered to deceive thereafter, weighed down, perhaps, by the tag — given his all-round abilities and left-arm swing bowling — of being “the next Sobers”. His last first-class match came during the 1983-84 rebel tour against a South Africa team including Graeme Pollock and Clive Rice. Later in life, battling throat cancer and depression, he led, according to the author Ashley Gray, a “nomadic, intermittently reclusive existence beholden to government and private handouts”.

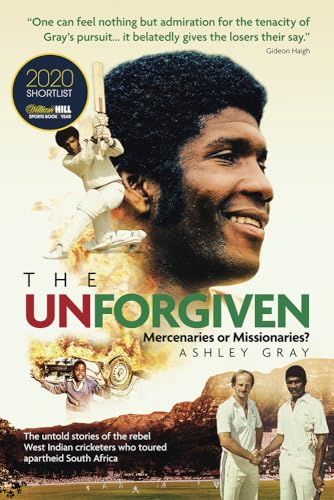

Gray captured the tale of the West Indian rebels in his book The Unforgiven. The basis of it was a straightforward one: to catch up with the 20 players who went on those tours in 1982-83 and 1983-84 and tell their stories. The questions the book asked, however, were anything but straightforward — while the context was specific, the scope was broad and universal: about the decisions we make in life, the choices we take and how they play out against a conflicting backdrop of punishment and forgiveness.

Gray’s book, The Unforgiven, told the stories of the 20 players who toured South Africa in the early 1980s

There were not many uplifting stories in Gray’s book. Among those hit hardest were the ones who stayed in the Caribbean, especially in Jamaica, where memories were long and opportunities, as a result, scarce. Austin went by the street name “Danny Germs” later in life and became destitute, homeless and dependent on drugs. He died a decade ago, aged 60.

Herbert Chang, a diminutive Jamaican dasher who once told the 6ft 8in “Big Bird” Joel Garner that he’d clip his wings in one regional match, was also reported to be living the life of a recluse on the streets down in Greenwich Town. David Murray, the wicketkeeper who played 19 Tests, lived in poverty around the streets of Bridgetown, Barbados, until he died three years ago.

Everton Mattis, from Jamaica, was another who struggled. With an uncertain future and opportunities scarce, he left for the United States, where he fell into alcohol and drug dependency for a while and spent some time in prison. Reflecting on his decision to go to South Africa, Gray quoted Mattis as saying: “If I could do it all again, I wouldn’t go. I am still suffering from South Africa.” The rebel tours cast the longest shadow over him, and others.

Yet some got on with their lives and remained defiant about their choices. Colin Croft, the fast bowler from Guyana, became a pilot. The Barbadian Franklyn Stephenson, who was very young when he joined the rebel tour, was eventually able to resume his first-class career in the Caribbean, when the ban was finally lifted in 1989, and enjoyed a decorated career in the county game. Since then, he has run a successful cricket academy in Barbados.

Austin and Alvin Greenidge opened the batting for the West Indies side in Cape Town during the first rebel tour in 1983

ADRIAN MURRELL/GETTY IMAGES

Perhaps the most well-known of the rebels was Lawrence “Yagga” Rowe — one of the most stylish batsmen to have played the game — and his subsequent sketchy relationship with his homeland highlighted the complexity of the issue. Having left and lived in the US after the rebel tours, he was on the verge of having his name attached to the pavilion at Sabina Park in 2011 by the Jamaica Cricket Association, until a public outcry caused a change of heart. The public remembered more than just his runs, almost three decades later.

Yet, when Julien died last week, Kishore Shallow, the president of Cricket West Indies, put out what felt to me like a finely judged and nuanced statement. The governing body could have ignored Julien’s passing, as it has when other rebels have died, but that would be to have ignored the contribution that he made to West Indies cricket before he went to South Africa. He was a World Cup winner, after all.

Rowe’s involvement in the tours stopped his name being attached to the pavilion at Sabina Park in 2011

ADRIAN MURRELL/GETTY IMAGES

His death, Shallow wrote: “Invites reflection on both the brilliance of his cricket life and the complex times through which he lived. His career reminds us that the story of West Indies cricket is not only about triumphs on the field but about the choices and circumstances that shaped generations of players and the region itself.”

Those choices, Shallow wrote, reflected “the difficult realities of that era and the pressures faced by players navigating competing demands of opportunity, conscience and circumstance” but that “all those who contributed to our regional game, in whatever context, are part of our shared story”.