(Credits: Far Out / Alamy)

Tue 21 October 2025 16:00, UK

“Bob Dylan is the father of my country,” Bruce Springsteen writes in his memoir, Born to Run.

In prose that matches his piercing lyrics, he continues, “Highway 61 Revisited and Bringing It All Back Home were not only great records, but they were the first time I can remember being exposed to a truthful vision of the place I lived. The darkness and light were all there, the veil of illusion and deception ripped aside.”

From that moment, Springsteen knew the sort of artist he wanted to be. He might have hit roaring heights with the likes of ‘Glory Days’, and sold over 30million copies of Born in the USA, but it’s his Dylanesque masterpiece for which he wants to be remembered. “If I had to pick one album out and say, ‘This is going to represent you 50 years from now’, I’d pick Nebraska,” ‘The Boss’ told CBS.

With Nebraska, the blue-collar star even rips aside his usual arsenal of adrenalised instrumentation to lay the true dark side of his nation bare in a stark open surgery of its heartland. Beginning with the bleak wail of a dissonant harmonica, ‘The Boss’ draws you into a world of despair and dead dreams. With a peculiar sense of despondent equanimity, he may as well mumble the line, “Me and her went for a ride sir / And ten innocent people died.”

For a man capable of rousing stadiums into rapture, it’s not the most rip-roaring affair, but for Springsteen, it represents something more than that. He was 32 at the time it was written and fresh from his breakthrough hit, ‘The River’, his first to land in the top ten. But he was left cold by the success that he had fought a lifetime to acquire.

“I just hit some sort of personal wall that I didn’t even know was there,” he bemoaned of the puzzling period. “It was my first real major depression where I realised, ‘Oh, I’ve got to do something about it.’” From this disposition, he started to look outward, both for the family he thought he “might have someday”, and at the society he wanted to live in. He says, “I realised none of those things are there.”

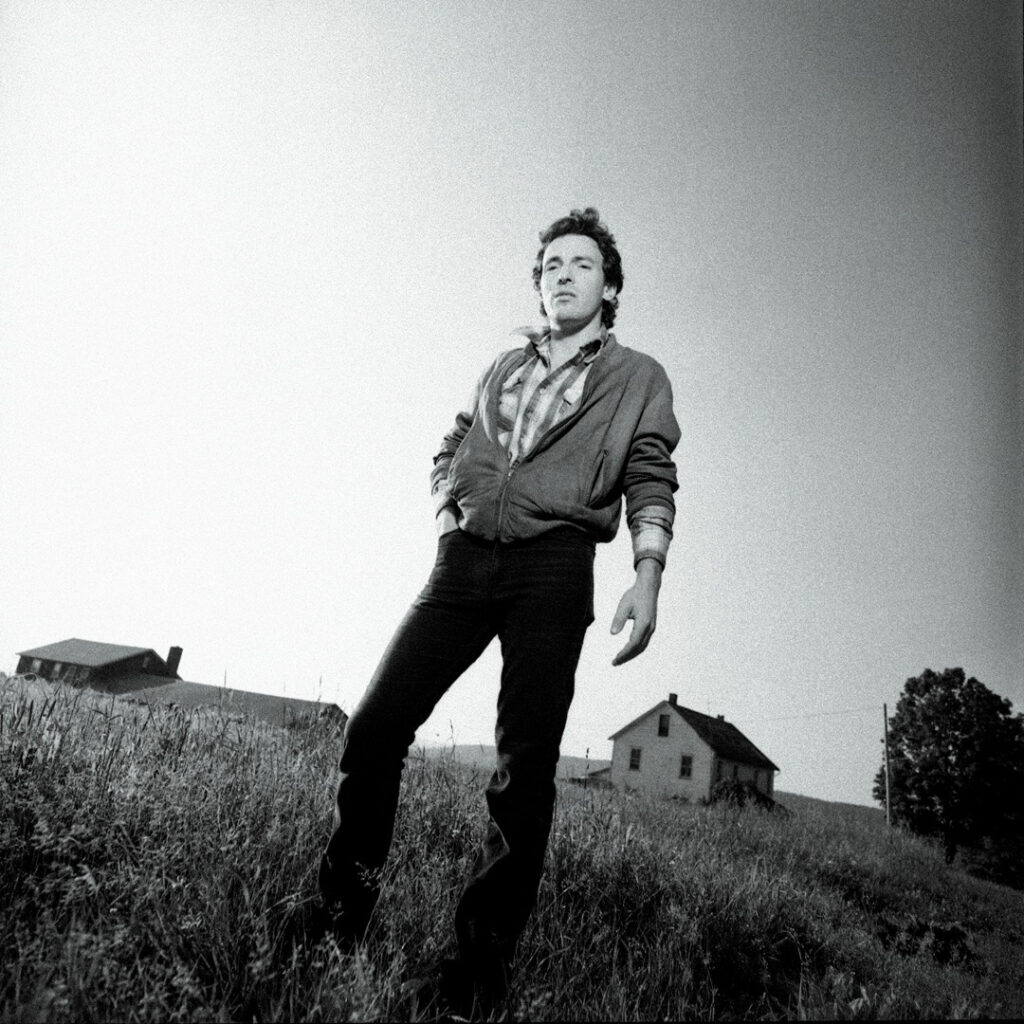

Bruce Springsteen, near the farmhouse where he wrote ‘Nebraska’. (Credits: Bruce Springsteen)

Bruce Springsteen, near the farmhouse where he wrote ‘Nebraska’. (Credits: Bruce Springsteen)

So, he went back to the start, back to that moment when Dylan ripped aside deception. “The first thing I’ve gotta do as soon as I get home,” he decreed, “is remind myself of who I am and where I came from.” It’s perhaps odd, therefore, where he finds his muse wandering over the course of Nebraska.

For the next ten tracks and 40 minutes, Springsteen doesn’t let his boot off the neck of America’s casually unspooling brutality. As he whisks up the tale of Charles Starkweather from the elemental background of Americana music, he pulls you into a heartless drama so equanimous it’s hardly dramatic at all. But it is profoundly unique.

Like a Cormac McCarthy novel stripped down and rendered in desolate strumming folk, Springsteen etches under the surface of something rarely addressed with such uncompromised clarity by an artist with such mainstream appeal: the violent heart of the USA. This is an intent and vision that he never abates from for a second on a perfectly realised record, honouring his heroes in Suicide by charting a similar path to their 1977 record ‘Frankie Teardrop’ five years on from its release.

While Suicide told the fictional tale of a murder-suicide perpetrated by a factory worker who goes out of his mind amid the grind of New York City, Springsteen swaps out the fictional element. “That’s one of the most amazing records I think I ever heard. I really love that record,” he said of the inspiration writ large across Nebraska.

But his masterstroke with the record is not his journalistic approach to reappraising Suicide, but the way he ditches the spooky drama of their work in favour of a more everyday reflection. In doing so, he brings to mind the casual, capricious and inevitable upheaval of Anton Chigurh in the movie No Country for Old Men when he quipped, “1958. It’s been travelling 22 years to get here. And now it’s here. And it’s either heads or tails. And you have to say. Call it.”

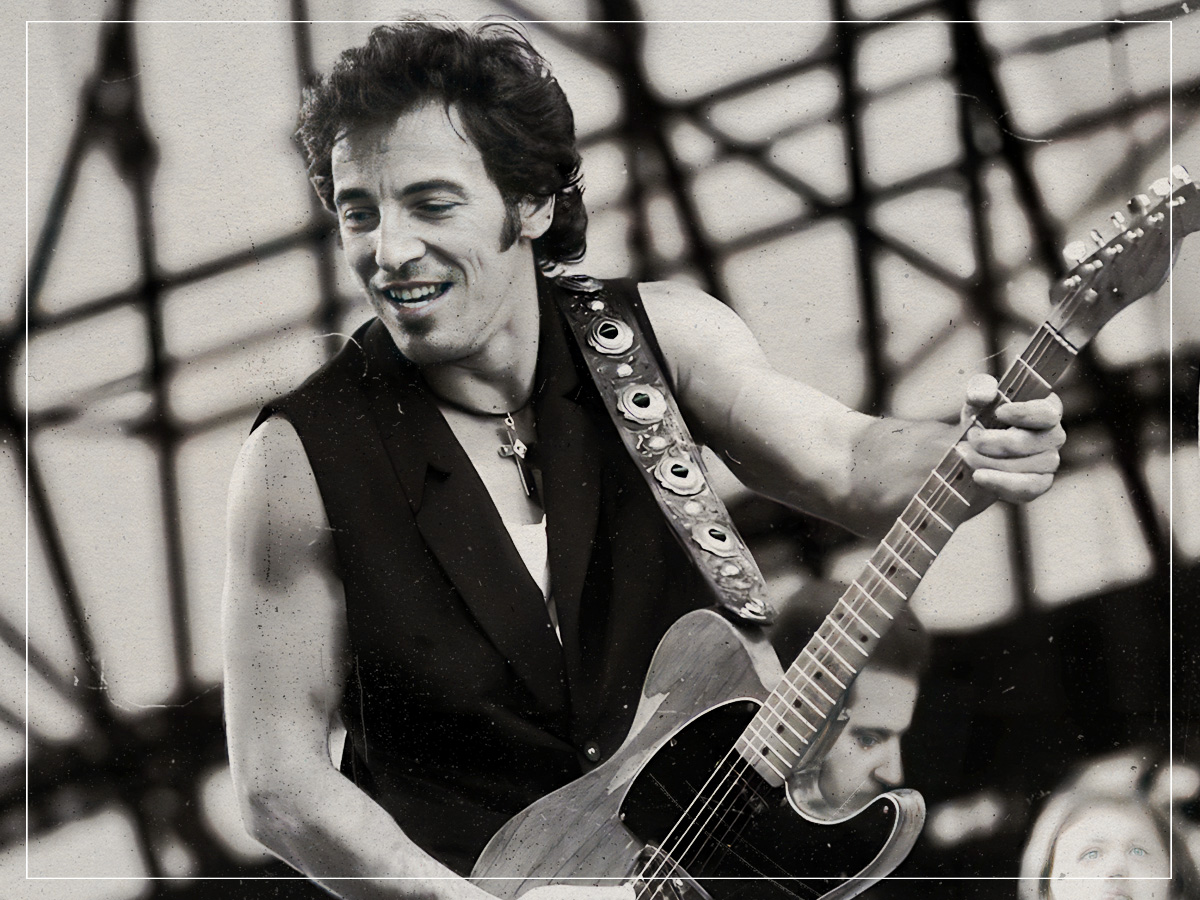

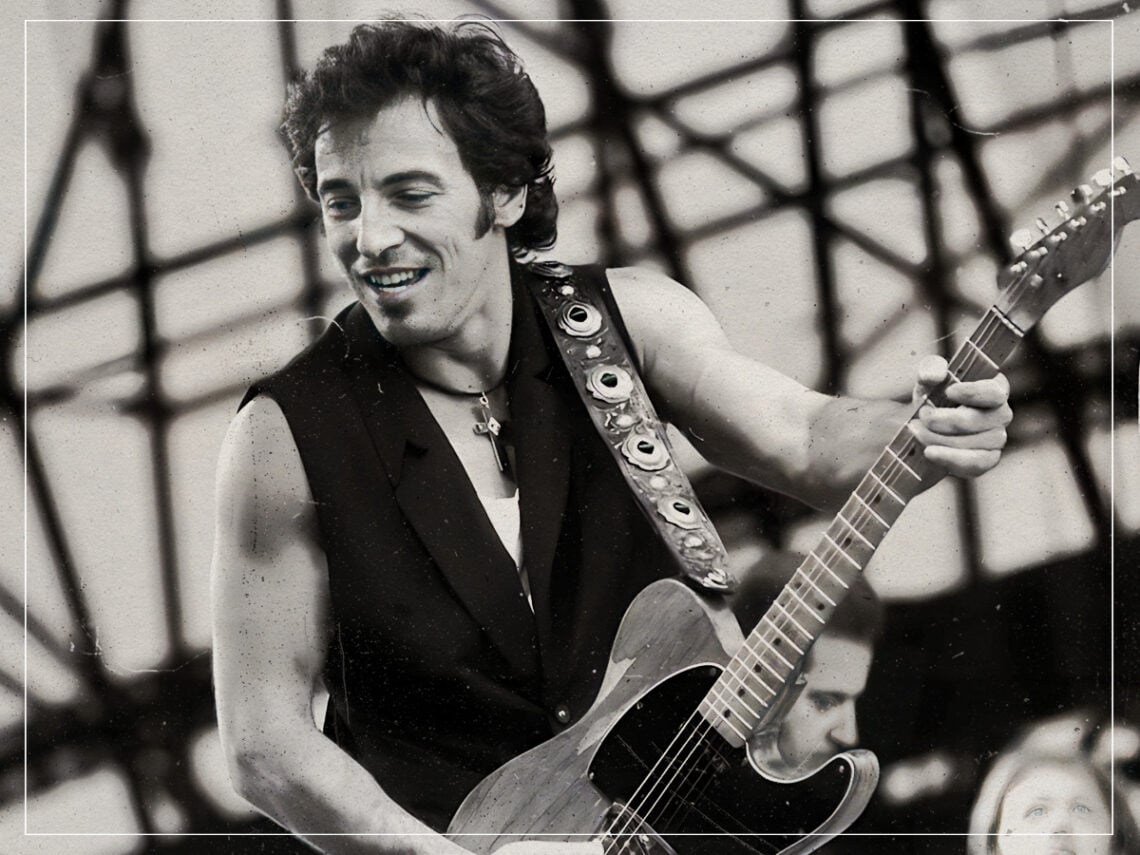

Bruce Springsteen in a photoshoot (Credits: Far Out / Danny Clinch / Bruce Springsteen)

Bruce Springsteen in a photoshoot (Credits: Far Out / Danny Clinch / Bruce Springsteen)

Alienated by success, Springsteen locked himself into his farmhouse and plucked away distantly on his guitar, his voice forever at the forefront of the mix with an echo chamber that amplifies the country croon he adopts. Meanwhile, harps of harmonica offer up a despairing wind, and that’s just about all he lays down on this most bare of albums.

The intent of this sparse, hollow structuring is clear and without subtlety, but that only adds to the bludgeoning impact, offering no respite from a reality we usually skirt around. It’s not that bleakness isn’t to be expected, but should it be accepted as an irrevocable undercurrent, a deepening coastal shelf upon which everything is built?

That’s perhaps where his boldest flourish comes into in – a flourish lesser artists wouldn’t have made: he offers a glimmer of hope at the final hurdle with ‘Reason to Believe’. However, more so than a moment of counterbalance, it seems this conclusion ties into the bleakness by encapsulating the modicum that allows the misery to perpetuate itself unchecked.

It’s as though he’s saying that as long as there is a glimmer of hope to sustain the dying American Dream, then it’s allowed to go on dying, leaving the previous nine chapters largely unaddressed. Just as fame failed to bring him any respite.

These short stories – snapshots of social realism – and their sustained, stark melodic backdrops are intricate works written humbly in blood and viscera. Cops looking the other way, gallows humour akin to the true crime quips captured in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, people pinning their hopes on a lottery, and murderers without remorse all make up one of the most exacting albums in American history. And it’s the one Springsteen considers his masterpiece now, just as he seemingly would have when he was a kid getting into Dylan ahead of time.

Related Topics