For the past few months, there have been plenty of headlines about 30-year UK government bond yields hitting the highest levels since the late 1990s. Depending upon political persuasion, some suggest this is a UK government-specific issue. But this misses the point.

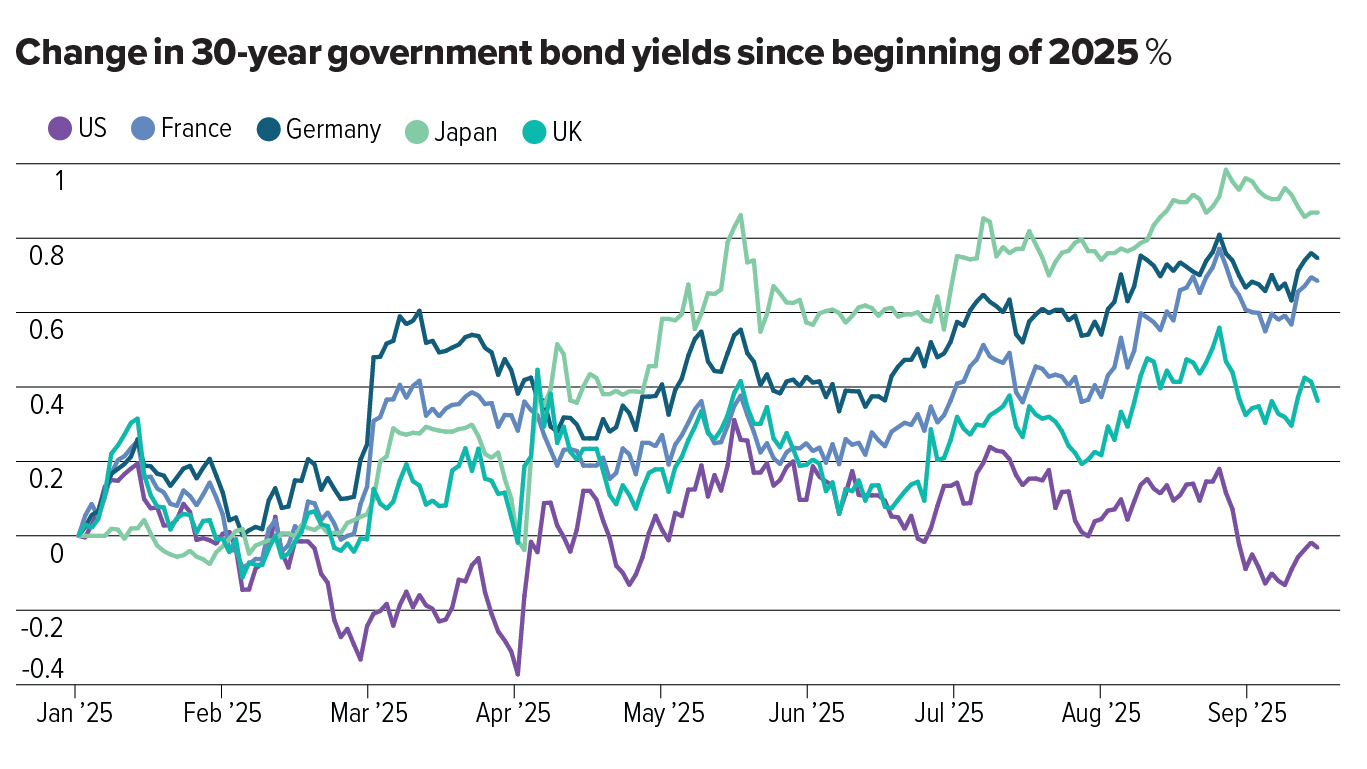

The chart below plots the change in borrowing costs on 30-year sovereign bonds across a range of countries. Two things should stand out: first, developed market government bond yields tend to be closely correlated around the world; and second, long-dated gilt yields have not risen as much as in Japan, Germany or France this year. Indeed, the increase in 30-year gilt yields since the end of May 2023 is almost identical to the increase in borrowing costs seen in Germany, France and the US, and less than the jump in Japanese borrowing costs.

Source: Fidelity International

Source: Fidelity International

Furthermore, if the UK really was in crisis and needed an IMF bailout, then you wouldn’t see the pound sterling at close to the strongest valuation versus its trade partners since before the Brexit referendum more than 10 years ago. Perhaps, as Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey said in comments recently, the level of the 30-year gilt yield doesn’t really matter for the UK economy.

That said, there are still risk events ahead for gilts, and we know from recent experience that bond investors can be very unforgiving when the UK chancellor puts a foot wrong. A test might come going into the UK Budget on 26 November, where any unexpected spending increases have the potential to cause chaos. But hopefully the current government knows that, and my assumption is that the UK Budget will most likely be a non-event for financial markets, as is usually the case.

Global phenomenon

So why have long-dated gilts performed miserably? As mentioned above, it’s a global phenomenon, and has come about because governments almost everywhere are running substantial fiscal deficits to try to boost growth, so the supply of long-dated sovereign bonds has been overwhelming investors.

Demand for longer-dated bonds has also been fading a bit, where ageing demographics and less need for longer-dated assets as part of people’s pensions has been a contributing factor. Longer-dated gilts are clearly not immune to whatever fiscal policy countries such as the US, Japan or Germany choose to pursue, where for example the surprise announcement of €1trn (£0.87trn) German stimulus earlier this year clearly had a profound impact on gilts, too.

Waiting for the green light

But we are bullish on gilts out to around 10-year maturity, where these maturities should be safer from the fiscal largesse experienced in other countries. The Bank of England has been one of the more hawkish central banks in the world over the past year, which was probably warranted because UK inflation has been proving stickier than in most other countries.

Now, we believe the Bank of England is very close to winning the inflation battle, where we should see inflation fall sharply from Q2 next year. Given economic growth remains tepid, then this should be the green light for the bank to cut rates next year.

Markets are pricing only two more cuts to 3.5% from the Bank of England and no more thereafter. If we’re right about the UK growth and inflation outlook, then the bank should be in a position to cut by much more than this from next year. Gilts should generate handsome capital gains as yields fall. And we want to be longer of UK-rate duration to try to benefit from this.

This article originally appeared in Portfolio Adviser’s October magazine