When Jean Kay started a brand-new multiple sclerosis treatment called Rebif in 2003, it cost $17,500 a year. That was pricey, but her insurance covered most of it, and the drug slowed the disease’s progress, improving her life immeasurably. Since then, though, the price of Rebif has risen four times faster than the rate of inflation, to more than $140,000 annually—with the share she’s had to pay bouncing up and down over the years until 2024, when her insurer decided to stop covering it at all.

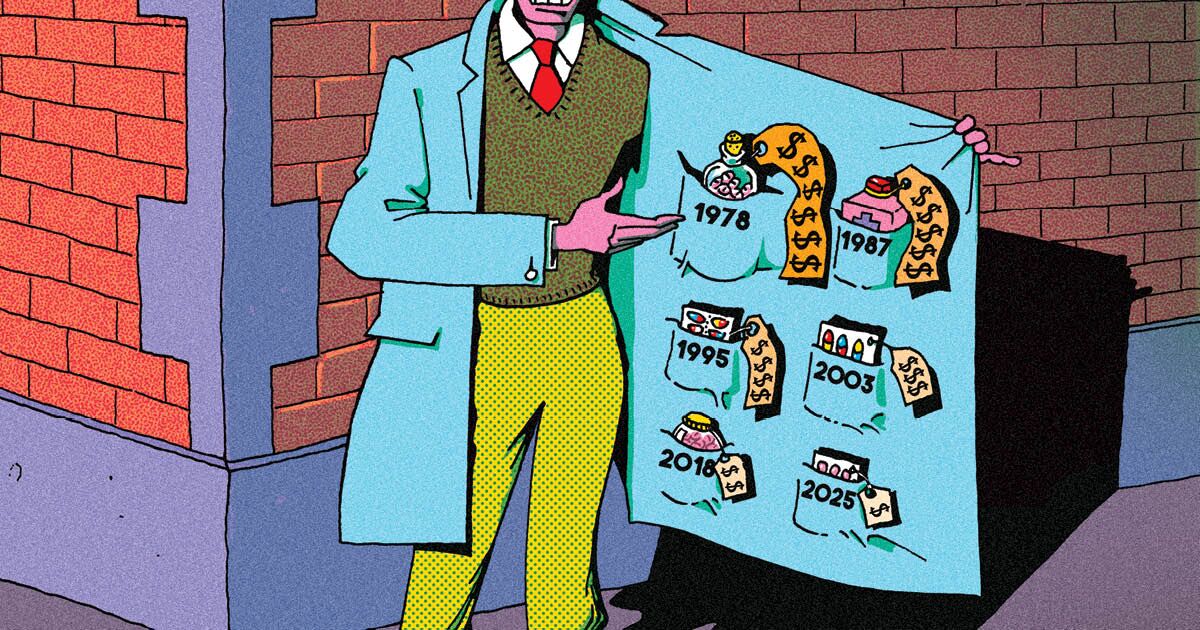

For decades, paying for treatment has influenced Kay’s career choices, led her husband to move 600 miles away for a job with insurance, and chewed up countless hours tracking costs and payment options. Rebif—an interferon, a class of medication first studied for MS in the 1970s and approved in the ’90s—is now the second-costliest treatment for the disease in the US. And Kay got this year’s prescription covered only after a last-minute appeal to her Medicare drug plan provider, UnitedHealthcare. “It’s just not right for them to raise the prices,” says Kay, 70, a nurse who stopped working because of her disability in 2016. “What justifies it?”