Africa’s wildlife is running on empty. A new Oxford-led study paints a stark picture of ecosystems across the continent operating on less than two-thirds of the natural energy they once possessed. The research highlights how the loss of large animals, once the driving engines of biodiversity, is reshaping life itself. The findings arrive as global leaders prepare for COP30, where the health of nature will again take center stage.

The Hidden Collapse Of Africa’s Ecological Power Grid

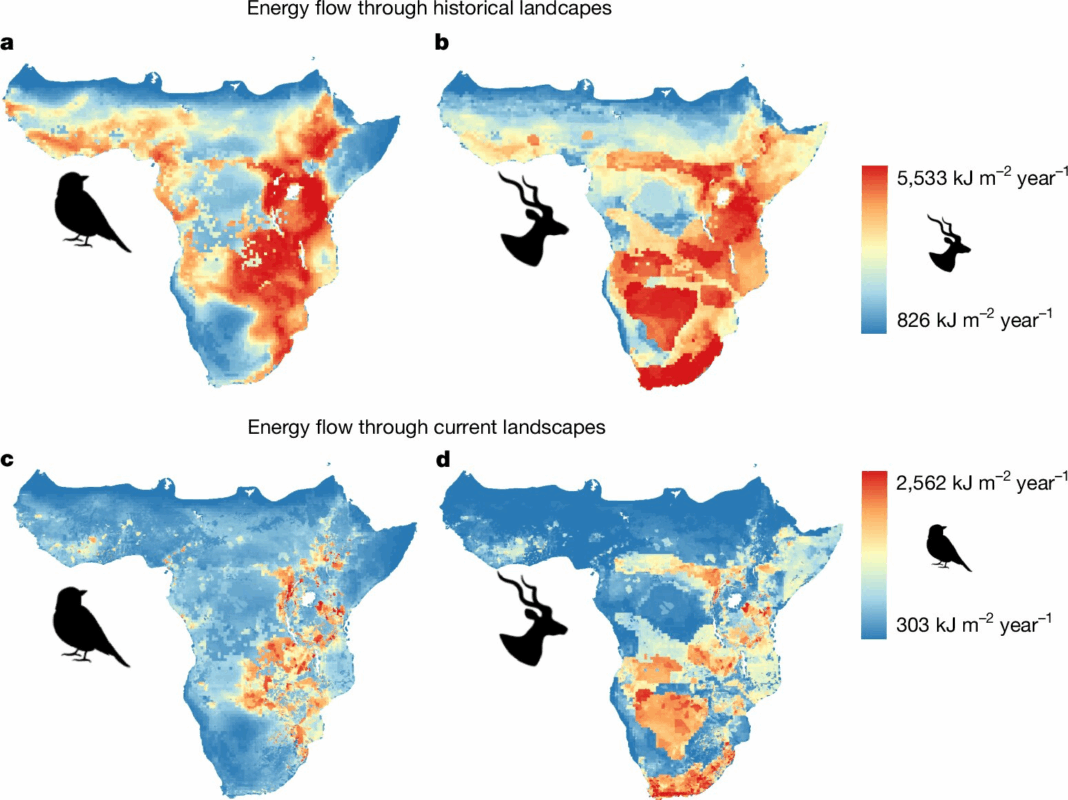

A groundbreaking study published in the journal Nature has revealed that Africa’s ecosystems have lost over a third of their natural energy since pre-colonial times. This “energy” is not metaphorical—it represents the biological power that fuels life-supporting processes like nutrient cycling, seed dispersal, and water regulation. Researchers from the University of Oxford mapped energy flow across more than 317,000 landscapes, covering over 3,000 bird and mammal species. Their findings show a fundamental weakening of the continent’s ecological infrastructure.

“The most important, and alarming, result is the collapse of ecosystem functions performed by Africa’s megafauna,” said Dr. Ty Loft, lead author of the study and a researcher at Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute. “Large wild animals are ecological engineers. Their roles can’t simply be replaced by smaller species or livestock. The loss of these giants has the potential to transform Africa’s ecosystems and landscapes.”

From elephants that once carved out savannas to rhinos that maintained open grasslands, Africa’s great animals once powered the continent’s natural systems. Their decline has left ecosystems fragile, fragmented, and increasingly dominated by smaller mammals and birds that cannot replicate the same ecological influence. This dramatic shift, scientists warn, could have far-reaching consequences not only for biodiversity but also for human livelihoods tied to the land.

Energy Flow: The Invisible Web Of Life

The Oxford team approached the study through the lens of “ecosystem energetics,” a framework that tracks how energy flows from sunlight captured by plants to the animals that consume them. This method reveals the pulse of life itself—a dynamic web connecting every organism.

“Energy flow is the shimmering web that holds together an ecosystem,” said Professor Yadvinder Malhi, co-author of the study and also at Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute. “By mapping how this web weakens or strengthens as animals decline or recover, we can see how life itself is reorganizing across the continent. This approach turns the concept of biodiversity loss into something physically meaningful.”

What emerges from this approach is not just a picture of species decline, but a measure of how much vitality an ecosystem has lost. In many regions, smaller creatures such as rodents, antelope, and songbirds now dominate what remains of the continent’s ecological energy flow. These shifts reshape landscapes, alter vegetation patterns, and even affect the carbon and water cycles. The study’s insights suggest that energy-based conservation metrics could redefine how we assess the health of nature worldwide.

Rebuilding Function, Not Just Populations

While the findings are sobering, the researchers also see hope. Across Africa, restoration programs—from Kenya’s elephant corridors to Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park—are showing that damaged ecosystems can recover. But restoration, they argue, must go beyond simply reintroducing species.

“Restoration isn’t just about bringing animals back, it’s about bringing back what they do,” said Dr. Loft. “An energetics approach gives practitioners a way to measure that, and to prioritize the functions that make ecosystems resilient.”

This shift in perspective could revolutionize conservation planning. By quantifying the energy contribution of species, ecologists can identify which animals are most critical to ecosystem function. Governments and NGOs may soon adopt these metrics to set more meaningful biodiversity targets—ones that focus on restoring natural processes, not just numbers.

Beyond Africa: A Planetary Wake-Up Call

What happens in Africa’s ecosystems may ripple across the globe. As the researchers emphasize, this is not merely a regional crisis but a planetary one.

“The loss of animal energy flow is not just an ecological story, it’s a planet Earth story which connects the fate of individual species to the functioning and stability of the biosphere itself,” said Professor Malhi.

By tying the decline of wildlife directly to the loss of natural energy, the study bridges the gap between biodiversity and planetary health. It underscores a profound truth: the disappearance of megafauna weakens the planet’s ability to regulate its climate and sustain life. The message is clear—saving the world’s remaining wildlife is not just about preserving beauty or heritage; it is about safeguarding the fundamental systems that make Earth habitable.