The Greenland shark is the longest-lived vertebrate on this planet, that we know of. It’s been showing up in news feeds for a few years now, described with breathless awe: “This shark can be 400 years old! It’s older than the United States!”

That’s not quite the giant Wowzer! for me that it might be. When I think human-level old, I think Gobekli Tepe. But an animal that lives for centuries, in our own world, not in a fantasy novel, really is amazing.

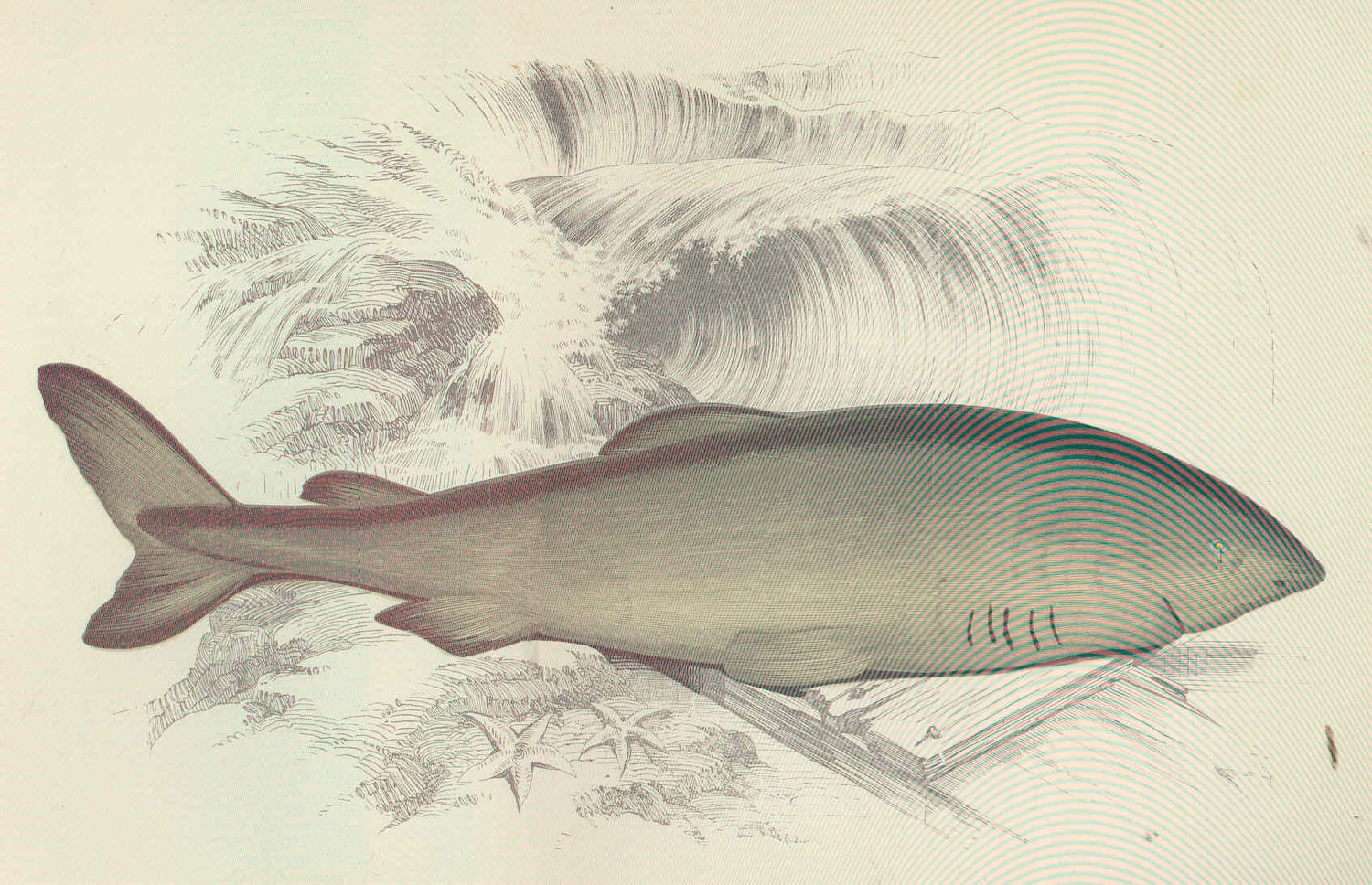

Sharks are creatures of near-myth anyway. So much of the truth about them is obscured by layers of fear, helped along by popular entertainment. We’re just starting to break through that fear, and coming closer to the sense of wonder. The Greenland shark, the shark that can live longer than any other vertebrate, is a wondrous thing.

Not only does it live a very long time, it’s a very large shark. Twenty feet (6m) or more. It’s not as massive as a great white, but it’s the same length or longer.

We’re still very much in the learning stages about this shark, another name for which is the grey shark. It’s classified as a sleeper shark, specifically Somniosus microcephalus. The name comes from the fact that it’s known to swim very, very slowly. Though not always; it can manage bursts of speed.

Slow movement, as in conservation of energy, is an adaptation to the environment where the species is most often found. That, unusually for sharks (who are generally creatures of warmer waters), is the cold, deep water of the Arctic. It can go as deep as 7200 feet (2200m), though it has been found in much shallower waters. It feeds on pretty much anything it can get, from crustaceans to seals, and it seems to be a scavenger as well as a predator.

Not only is it (at least sometimes) a slow swimmer, it also grows very slowly. Very, very slowly. As little as a couple of centimeters a year. All the way up to 600 centimeters. That adds up to decades. Centuries.

As with other sharks including the great white, females are larger than males. The great old ones mostly likely are grandmother sharks. And they may not be sexually mature until they’re at least 150 years old.

That’s mind-blowing for a human. We’re long-lived compared to many animals on the planet, but to a Greenland shark, we’re as relatively ephemeral as a dog or a cat.

Many or most of these sharks are blind, thanks to a parasite that lodges in their eyes. It’s not the disability it might be for a land animal: there’s no light in the deep ocean, and their sense of smell is acute, as is their ability to detect vibration in the water. Clearly they have no trouble eating enough to survive and thrive, though human interference and climate change are a serious threat.

One particularly potent adaptation to both cold and depth makes the Greenland shark actually poisonous. Their flesh when fresh is full of toxins, including trimethylamine oxide (TMAO), which can produce symptoms similar to extreme intoxication and can be fatal. It can however be prepared so that it’s safe to eat, as it is in Iceland, where it’s called Hakarl.

I would like to know who discovered this and how they did it, because it’s a laborious and lengthy process. Desperation, and starvation, must have played a part in it.

Slow growth and slow movement might be a problem for an animal in this rapidly changing world, but the Greenland shark has one advantage that we’re just beginning to understand. It appears that females are very, very, very fertile. As in hundreds of eggs per pregnancy.

They are what’s known as aplacental viviparous sharks. They give birth to live young, but the young don’t obtain oxygen and nutrients from the mother through a placenta. The baby shark feeds on its yolk sac—and its fellow baby sharks—until it’s ready to be born.

At that point it’s about 15 inches long (35-45cm), and it’s a fully formed predator, a miniature version of its mother. She doesn’t nurture it. Once it’s born, it’s on its own.

We don’t know all the details of its reproductive cycle. Exactly how males and females breed, how long the gestation period lasts, where or when the babies are born—these are mysteries that have yet to be solved.

We don’t even know for sure how extensive the Greenland shark’s range is. An individual turned up recently in the Caribbean, off the coast of Belize. The waters in the region are extremely deep, down to 25,000 feet (7600m), which means that, however warm the shallows may be, the depths are more than cold enough to support a Greenland shark. For all we know, they’re everywhere in the deepest parts of the Atlantic. If the water is cold enough, and they’re not stopped by marine barriers, they could be anywhere. We just haven’t happened across them.

icon-paragraph-end