The Christmas Island shrew was a small, short-legged creature with a pointed muzzle. Like other shrews, it resembled a mouse and weighed around 4-6 grams (under 0.2 oz). It was once abundant on Christmas Island, an Australian territory in the Indian Ocean, about 224 miles (360 km) south of the island of Java. It was common to hear the small shrew’s thin cry in the night. But now, Crocidura trichura has been officially declared extinct.

It was humans who wiped it out, though not directly. When the first recorded settlers came in the 17th century, they brought rats that decimated the population. The rats’ parasites brought even more trouble. Non-native cats and snakes may have been the final straw.

But this extinction isn’t just tragic. It’s also quite mysterious.

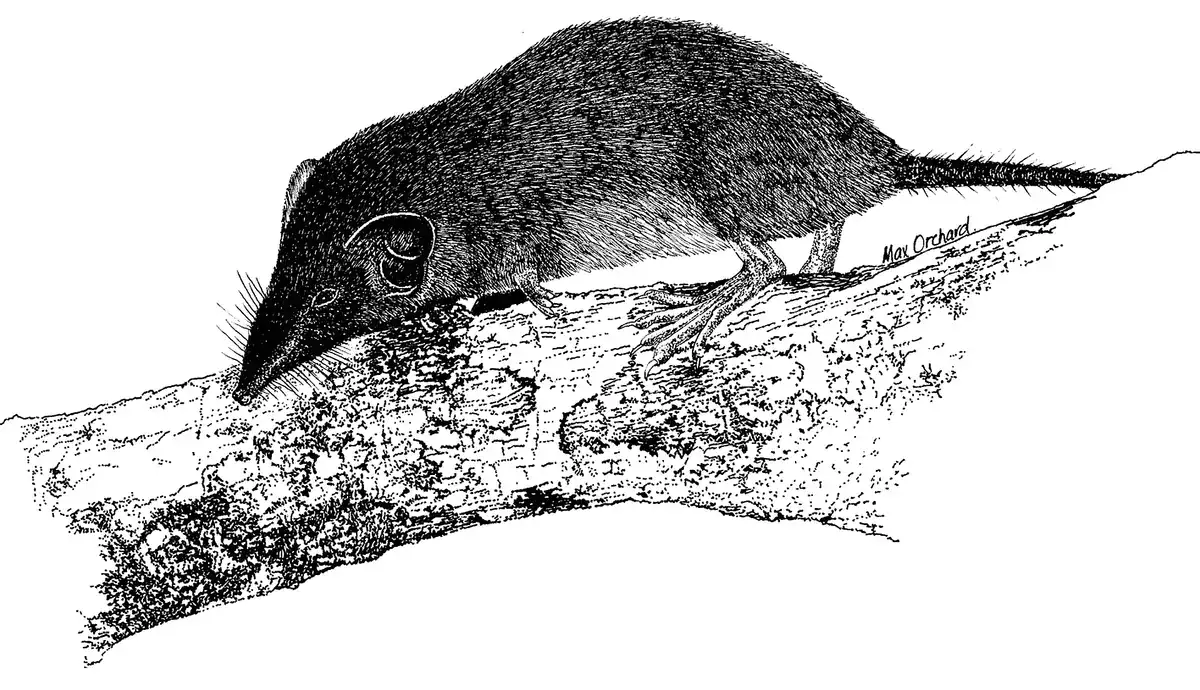

There are very few photographs of the Christmas Island shrew. This drawing by Max Orchard.

There are very few photographs of the Christmas Island shrew. This drawing by Max Orchard.

In 2023, a team of researchers published a paper that calculated the probability that the shrew is extinct at 96.3%. Surveys couldn’t see it and neither could cameras. It wasn’t impossible that it was still alive somewhere, just very unlikely. A subsequent IUCN update confirmed this likelihood.

There is conclusive evidence that Crocidura trichura populations declined dramatically since 1900. In fact, some suspected it went extinct not long after that. But in 1985, researchers spotted an individual and thought the species could bounce back. This turned out not to be the case.

“This is one of the most mysterious of extinctions,” says Professor John Woinarski at the Charles Darwin University, Australia, and lead author of the paper, for the BBC.

“This shrew persisted — but obviously in only very small numbers — long after it was initially thought extinct in 1908. But with only four records over the last 120-odd years, its status has been extremely challenging to resolve. Its loss highlights the disproportionate rate of extinctions of island biota, and their susceptibility to introduced plants, animals and disease.”

A Rough History

Much of Christmas Island’s area is now a natural park, but this wasn’t always the case. In fact, the remote island had its fair share of problems. The island was first discovered in the 17th century, but the first attempt at exploring the island was made in 1857. It was annexed by Britain not long after that. The British were mostly interested in phosphate mining.

The island was managed by Britain through a corporation, and then through Singapore. During WWII, the island was invaded by Japan, which torpedoed a freighter that sank off the coast. The island was subsequently shelled and bombed a few times until the Japanese force surrendered. The United Kingdom transferred sovereignty of Christmas Island to Australia in 1958, for a payment of $20 million.

Throughout all this, the wildlife on Christmas Island suffered tremendously. The island had been uninhabited by humans until the 19th century. As soon as the settlers came in, two species of native rats became extinct. The Christmas Island pipistrelle (a small bat) is also presumed to be extinct. Now, the same is assumed for the shrew.

A related grey shrew. Image via Wiki Commons.

A related grey shrew. Image via Wiki Commons.

Like many islands, Christmas Island’s isolated geography created unique, endemic creatures that were extremely vulnerable in the face of new species.

For the Christmas Island shrew, this marks a tragic end to what was a remarkable adventure. Tens of thousands of years ago, a family of shrews (or perhaps a pregnant female) accidentally made its way to the island. Most likely, on a floating log or some other vegetation. They landed on this relatively quiet island with no major predators. For many years, they thrived. When European naturalists described the island in the 1890s, they remarked that the little creature is common all over the island.

A Tragic Loss

Change happened very fast. In 1900, black rats were accidentally introduced. By 1908, naturalists couldn’t find any more Christmas Island shrews.

Somehow, a few individuals lived on.

In the 1950s, bulldozers were clearing a patch of rainforest for mining. They found a couple of shrews and released them, without thinking about conservation. The next sighting was in 1984, when two biologists clearing a rainforest track came across a female shrew. They kept it in a terrarium for over a year, feeding it grasshoppers. But they too didn’t consider that this was an opportunity for conservation. A male shrew was found just a few months ago and kept in a separate terrarium.

This was the last time anyone ever saw a Christmas Island shrew.

Since then, plans have been drawn. If a single pair were to be found, there could be a chance for the species. Researchers are wary to declare a species extinct, because that means cancelling all funding for it, and errors have been made. This funding could (and on occasion, has) made for a last-ditch effort to conserve the species. But no one has seen a shrew for over 30 years.

It doesn’t seem like a big story. Just another species trying to survive in the deluge of changes brought by mankind. But the Christmas Island shrew has a striking story. It survived an unlikely journey to the island, and then it survived for over 50 years after being thought extinct. This small species was more adaptable than anyone thought.

Yet, even this wasn’t enough.

The shrew’s loss is a harrowing reminder of how difficult it is to protect animals in the time of the Anthropocene, and how early conservation policies can make all the difference.

We don’t often hope that researchers are wrong. This time, we do. Perhaps there is a small group hidden somewhere that no one has looked. Perhaps, a fortunate biologist will come across a mating couple and re-launch a conservation process. Or perhaps, in time, the species could truly bounce back.

But for now, the forest is silent.