Herbalist books have been popular for centuries. This new AI-written generation is a disgrace. Image in Creative Commons.

Herbalist books have been popular for centuries. This new AI-written generation is a disgrace. Image in Creative Commons.

At the top of Amazon’s “Herbal Remedies” bestseller list, The Natural Healing Handbook looked like a typical wellness guide. With leafy cover art and promises of “ancient wisdom” and “self-healing,” it seemed like a harmless book for health-conscious readers.

But “Luna Filby”, the Australian herbalist credited with writing the book, doesn’t exist.

A new investigation from Originality.ai, a company that develops tools to detect AI-generated writing, reveals that The Natural Healing Handbook and hundreds of similar titles were likely produced by artificial intelligence. The company scanned 558 paperback titles published in Amazon’s “Herbal Remedies” subcategory in 2025 and found that 82% were likely written by AI.

“We inputted Luna’s author biography, book summary, and any available sample pages,” the report states. “All came back flagged as likely AI-generated with 100% confidence.

A Forest of Fakes

It’s become hard (sometimes, almost impossible) to distinguish whether something is written by AI. So there’s often a sliver of a doubt. But according to the report, The Natural Healing Handbook is part of a sprawling canopy of probable AI-generated books. Many of them are climbing Amazon’s rankings, often outselling work by real writers.

What’s especially troubling is the nature of the genre. These books offer health and lifestyle advice. They have recipes for homemade tinctures, teas, and syrups, and readers often buy them looking for alternatives to pharmaceutical medicine.

“There’s a huge amount of herbal research out there right now that’s absolutely rubbish,” said Sue Sprung, a medical herbalist based in Liverpool, in an interview with The Guardian. “AI won’t know how to sift through all the dross… It would lead people astray.”

And lead them astray it has. Inside the Natural Healing Handbook, readers are urged to “look inward” for healing, while being offered recipes with ingredient lists that don’t match the instructions.

“On page 84 there is a recipe… and then in the instructions it tells you what to do with a completely different list of ingredients!!!” wrote one frustrated reviewer.

Another added: “There are incomplete recipes in which the instructions were not written…”

Review Highlighting Incomplete Instruction. Credit: Originality.ai

Review Highlighting Incomplete Instruction. Credit: Originality.ai

One lone reviewer, Ismail G. from the U.K., managed to call it out: “I guess it is written by AI, full of inconsistencies.”

AI Slop Strikes Again

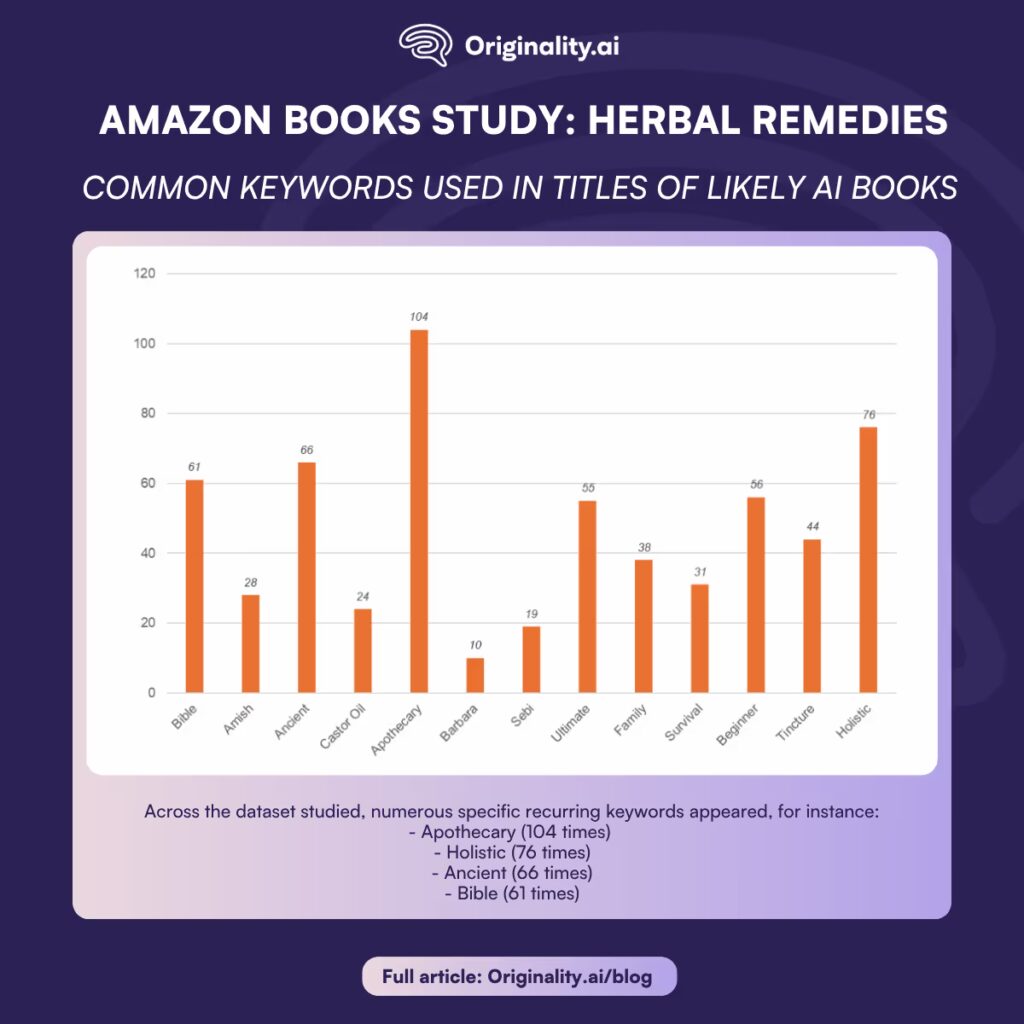

The problem is scale. It’s not one book that slipped through the cracks. The entire genre is infiltrated by what it calls “AI slop.” They even seem to have a pattern:

76% of authors used names like Rose, Fern, or Sage—vaguely earthy and comforting.

54% of summaries were decorated with the 🌿 leaf emoji.

87% of titles repeated the same keywords: “Apothecary,” “Ancient,” “Holistic,” “Bible.”

The average price was about $3 cheaper than human-written titles—and the content was thinner, by around 50 pages.

Even more concerning: many of these books referenced controversial alternative health figures such as Barbara O’Neill and Alfredo “Dr. Sebi” Bowman. Both have promoted unproven—and in some cases dangerous—treatments for serious conditions like cancer and AIDS.

In The Ultimate Beginner’s Guide To Herbal Remedies, another book likely written by AI, a fictional author named Elaine Wilder claims echinacea “resolved” her mother’s chronic bladder infections—despite no mention of dosage, contraindications, or side effects.

Echinacea, while supported by some studies for limited immune support, is NOT a silver bullet—especially not for children, pregnant women, or those with autoimmune disorders. But none of that appears in the book.

“These likely AI-generated fables… neglect details, consequences and nuance,” the report warns. “Only a primary care provider—or even an in-person herbalist… will be able to speak to you about your medical situation.”

Amazon’s Crisis

To the casual shopper, The Natural Healing Handbook seems credible. It has over 500 glowing reviews, a sleek cover, and even editorial blurbs from “experts” like Sarah Wynn, who called it “a visual and practical treasure.” But Sarah Wynn doesn’t exist. Neither does her company, Wildcraft Journal.

Amazon insists it enforces content guidelines and uses both proactive and reactive detection tools. “We invest significant time and resources to ensure our guidelines are followed,” a spokesperson said in a statement, “and remove books that do not adhere.”

But industry experts remain skeptical.

“Any book that is fully AI-written should be labelled as such,” said Dan Conway, CEO of the UK Publishers Association. “And AI slop must be removed as a matter of urgency.”

Until that happens, the burden falls on consumers.

The red flags are there—if you know where to look:

Nature-themed names that sound a little too poetic

Summaries full of emojis and repeated slogans like “take control of your health”

Photos with suspicious watermarks, or author profiles that lead nowhere

Often, it’s not until the book is in hand that readers discover the recipes don’t work or the tone feels eerily generic. Some titles even have multiple versions floating around—nearly identical except for a changed title or rearranged paragraphs, like an AI-powered form of A/B testing.

Where This Leaves Us

AI is flooding niches that once relied on careful expertise and centuries of accumulated knowledge. Real writers are being drowned out by machines regurgitating fragments of folklore scraped from the internet.

“This is a damning revelation of the sheer scope of unlabeled, unverified, unchecked, likely AI content that has completely invaded [Amazon’s] platform,” wrote Michael Fraiman, author of the Originality.ai report.

The report looked at herbal books, but there’s likely many other niches hidden

Amazon’s publishing model allows self-published authors to flood categories for profit. And now, AI tools make it easier than ever to generate convincing, although hollow, manuscripts. Every new “Luna Filby” who hits #1 proves that the model still works.

Unless something changes, we may be witnessing the quiet corrosion of trust in consumer publishing.