It’s a dreary Monday evening at the tail end of the UK’s third Covid-19 lockdown. As I step out of the Southwark tube station, I catch a reflection of myself in the window of a deserted office block. My face is red and blotchy, my eyes distant and glassy.

I’ve spent the last 30 minutes trying to hold back what I now understand to be a panic attack. Bubbling anxiety and depression have been a part of my life for the best part of a decade at this point, but it’s getting worse. Earlier that month, I’d been told I could not access an ADHD assessment within my local NHS Trust. My work was suffering badly, and I felt disconnected from my mates and family.

By this point of the pandemic, we’re allowed to mingle in very specific circumstances. Team sport is legal again. As I round the corner towards the five-a-side pitches, my mood starts to lift.

To the untrained eye, the Colombo Centre is just your average 3G cage nestled between high-rise apartment blocks and council housing in an interchangeable neighbourhood of inner London. It’s a bit shabby; every week, I spend a few minutes picking up discarded bottles and shifting some leaves out of the goal mouths. Sometimes the local kids that I shoo off the paddock help, sometimes they take the piss. The ritual is all part of my pregrame process. This week, it feels particularly grounding.

Me and my best mates have started a new team, the mighty ‘Naby Sarr up Top?’ Don’t ask about the name. We’re pushing for a league title. I’ve kept two clean sheets on the bounce. Crucially, there will be pints when the final whistle blows.

I just about manage to smile through the pleasantries as the lads start to arrive. There’s not much to catch up on, really; nobody’s up to anything bar Zoom quizzes and lengthy Xbox sessions. It makes it easier to hide how shit I’m feeling.

After a quick warm-up, we’re into the game, and all those negative thoughts wash away. Far from the timid and cowed wretch that turned up to the cages, I’m barking orders, laser-focussed on the game and prowling my area with authority. We win. The debrief takes place in a damp pub garden over a couple of overpriced but life-giving pints of Neck Oil. I feel normal for a couple of hours. As I get back on the tube, I’m already counting down the hours until we can do it all again.

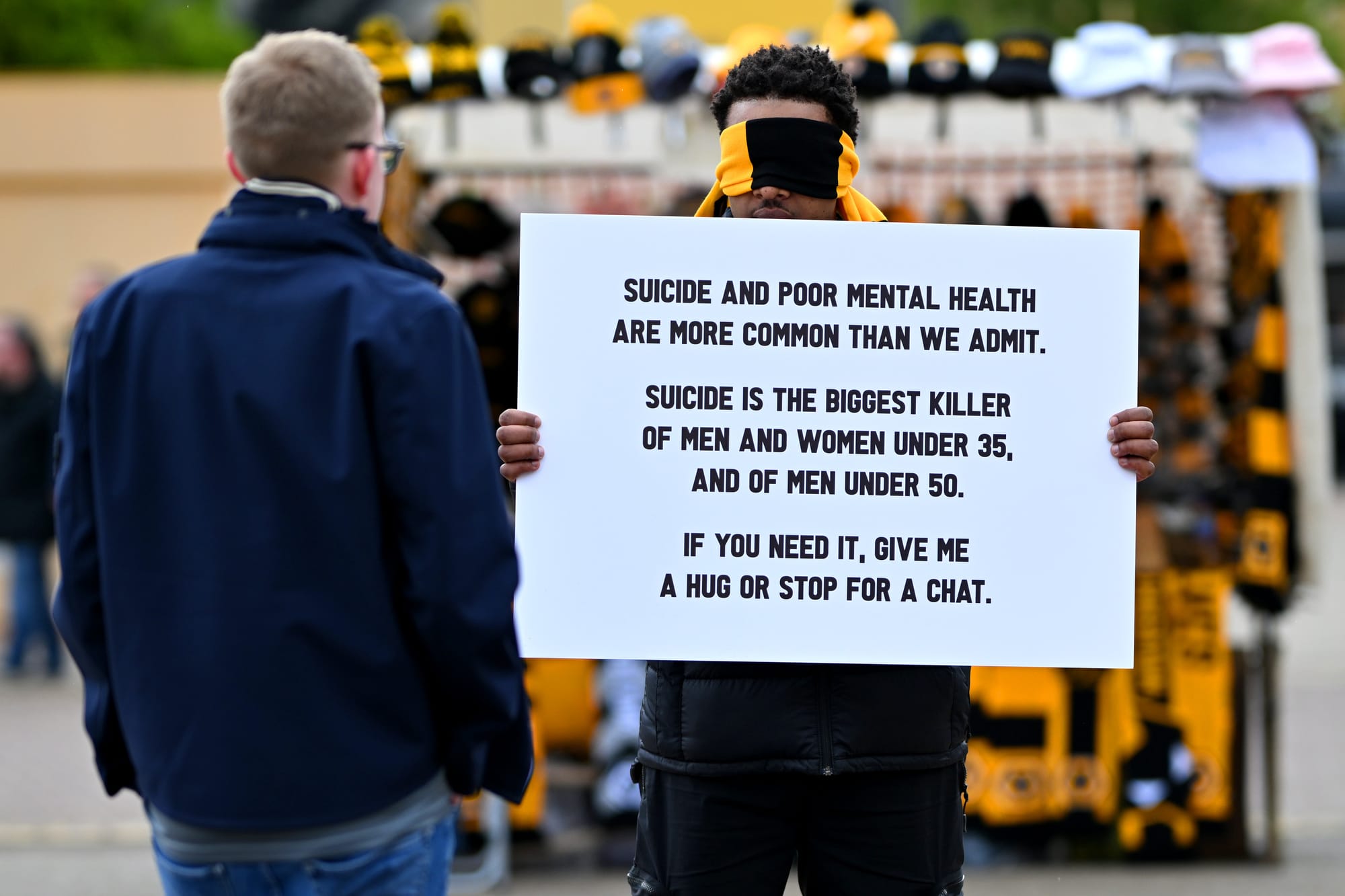

You don’t need me to tell you that men struggle to talk about their mental health, or that suicide is the biggest killer of males under the age of 50 in most developed nations across the globe. We’ve become well-versed in talking about how big a problem this is; we’re aware of the economic factors at play in our disenfranchisement and the aching loneliness that far too many men feel in the modern world. That doesn’t mean we have come up with any real, coherent strategy that meets the scale of the problem.

Some 3.8 million people accessed mental health services within the NHS last year, but millions more are shut out of adequate care. The need for ancillary solutions that can supplement medical care is greater than ever. Adjunctive treatment—non-medical interventions that can include the promotion of healthy lifestyle, holistic therapies, or ‘social prescribing’, the referral of patients to free-to-access community-based pastimes such as the performing arts or sport—are increasingly becoming part of the treatment strategies of oversubscribed health systems. In 2024, the number of people given social prescriptions in the UK tripled compared to 2021. Football has a role to play in that movement.

Earlier this year, Forest Green Rovers and the Labour MP for Stroud, Dr Simon Opher, announced a new scheme called ‘Football on Prescription’. The pilot gives people within the NHS Gloucester Trust presenting with mild mental health problems, such as anxiety or depression, the opportunity to watch the club for free with a friend; men over the age of 50 can also take part in walking football twice a week. It builds on Dr Opher’s 25-year career as a GP; he ran a similar scheme called ‘Comedy on Prescription’ (consistent branding) that saw patients attend stand-up shows fronted by Instagram ranter Jonathan Pie. That idea caught the attention of Forest Green Rovers chairman and noted sustainability campaigner Dale Vince.

“I was telling Dale about all of this, and he goes: ‘Why can’t we do that for football?’” says Dr Opher. “He’s very keen on mental health campaigning. He loves football in terms of its community sense.”

Dr Opher’s interest in the use of social prescription stems from what he views as an “over-medicalisation” of mental health treatment. He reports “shocking” statistics that 8.7 million people in England are currently on antidepressants.

“A lot of people come to the doctor saying, ‘I’m feeling a bit low’. If your mental-health waitlist is six months, and the doctor’s first reflex is to help their patients, they might put them on antidepressants. Sometimes, people really do need that, but there are other alternatives. You should always try to steer people into something different, that may be counselling if you can get it, or social prescription.”

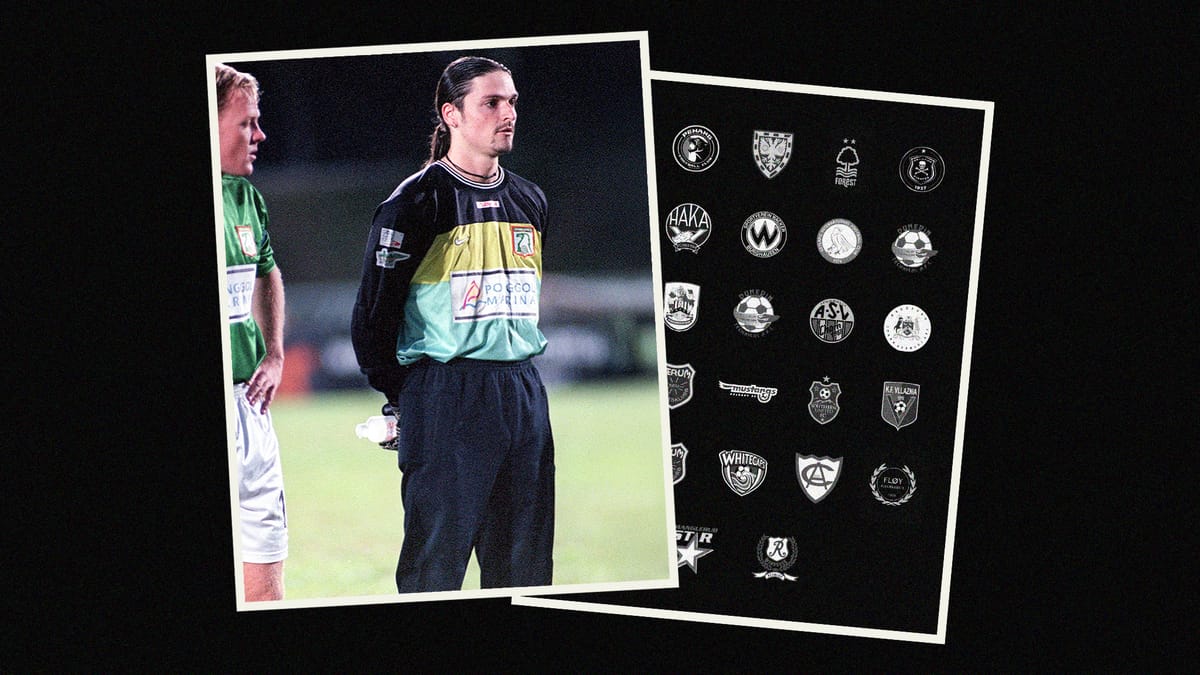

Lutz Pfannenstiel: Life lessons with football’s record-breaking nomad

Lutz Pfannenstiel is football’s greatest nomad…

While Football on Prescription has garnered more headlines of late, the idea of using football as an adjunct in mental health treatments is not new. For almost two decades, Coping Through Football (CTF) has provided space for both adults and children experiencing mental ill health in north east London to take part in free-to-access football. The scheme is run in collaboration between London Playing Fields Foundation (LPFF), the North East London Foundation Trust (NELFT, the NHS trust for the London Boroughs of Barking & Dagenham, Barnet, Redbridge, and Waltham Forest) and Leyton Orient Trust.

Over six sessions per week, participants come for a two-hour practice, made up of a warm-up, skills development, organised games, and a 20-minute session that looks to instil tenets of healthier living. Alex Welsh, the CEO of LPFF, explains that the original idea behind the programme was to help men suffering from severe mental health conditions—most commonly schizophrenia—build their self-esteem, improve their fitness and give them a network.

“One of the most marginalised groups in the whole country is people who’ve got long-term mental health issues,” Welsh says. “We had this idea that we could transform community mental health. We wanted to focus on people at the more extreme end of the mental health continuum, with serious issues like schizophrenia. How do we ensure that these patients come into contact with health professionals, and once they’re there, how can we provide them with a therapeutic intervention?”

LPFF sees people with various diagnoses take part. Many of the children referred to the scheme are experiencing mental health issues in relation to another condition, such as autism, learning difficulties or chronic pain. Crucial to the genesis of the project was the idea that patients who experience additional prejudices are encouraged to attend. Back in the early 2000s, there was a sudden influx of refugees from war-torn countries like Kosovo, Sudan and Somalia. Even more established ethnic minority groups experience worse health outcomes: Welsh quotes NHS figures that show black men are six and a half times more likely to be hospitalised due to poor mental health.

The majority of participants in the scheme were initially found through outreach teams. As the scheme matured, more and more patients were referred through the NHS. An early intervention team engages with parents whose children are exhibiting early signs of complex mental health conditions, many of whom are left with few options, as it is tricky to establish a diagnosis, and may have been pulled from the education system when their needs aren’t being met.

“We were worried that, if it was left too late, these children would develop more embedded mental health issues, and then have to endure an adult life with institutionalised care,” Welsh says. “If we can catch them when we first see the signs of psychotic behaviour, we could help prevent them from falling into that crevasse.”

And there is growing anecdotal evidence to suggest that such schemes can produce tangible benefits for the individuals who take part.

Twelve years ago, Dan* was in a really bad way.

He had just gone through a painful divorce. A knee injury in his earlier days meant he was unable to exercise much, leading to feelings of depression and anxiety exacerbated by his perilous working situation. He was only really able to hold down shift work, with the irregular working hours leaving him unable to forge meaningful connections with people. He was isolated and lonely.

“To tell the truth, I wasn’t coping,” he says.

A local employment service had told him about CTF; someone else he had met at the service was also going along, so he thought he’d give it a go. What he found was a network that helped him overcome both his existing struggles and further trauma.

“CTF has been with me through some of my hardest times. I came to the project as my marriage ended, and they also helped me through the end of my second marriage.

“When my second marriage ended, I was in a terrible state. I was really, really anxious. I felt angry about my life. I’d also witnessed a road traffic accident. That left me with a lot of feelings: I was angry that I’d seen someone’s life be taken just because somebody was not being careful.

“Sometimes I was so angry at home that I punched the wall and bruised my knuckles. Football helped me to focus myself; I learned to release the anger through pushing myself in football. CTF has helped me to stay calm.”

His involvement in the scheme has given him more confidence. It enabled him to enrol in first-aid courses, which helped him take better care of his elderly diabetic father. It gave him a real friendship.

An Olympic gold medalist walks into Wetherspoons

Chioma Ajunwa is a history maker with one heck of a story to tell…

“At CTF, I’ve made good friends with one person. We talk on WhatsApp and text. We go out for meals, we go to the pub, and I share a lot of my worries with him.

“Life is much better now since coming to CTF. I go out to watch films, and I go on holiday twice a year. I only just started doing that two years ago. I’ve even progressed in my football, although I’m in my forties. I am now a player-manager at a club. I know how to encourage people in a positive way. I try to find the right words and not focus on the negative. I can explain difficult things about football in simpler ways and encourage them not to worry about it.”

Dan’s story certainly rings true with me. Taking part in team sport socially or competitively—since moving to Germany I’ve actually picked up playing rugby again after a decade away from the sport (please don’t judge, I don’t wear jeans with leather shoes and ask the landlord to put the Champions Cup on instead of the football in the pub, I certainly have never called Twickenham, ‘HQ’)—has had a material improvement on my wellbeing, while joining Union Berlin has connected me with a real community in an international city where it’s easy to remain in a closeted enclave of English speaking transplants. However, is there academic evidence to suggest that it can be used as an intervention that can produce results on a wider level?

In order to establish the efficacy of their scheme, CTF worked alongside clinical psychologists to create a framework and track results. Dr Oliver Mason, an academic researcher in clinical psychology at the University of Surrey, helped with that endeavour. He explains that while it is clear that social prescribing is certainly of benefit to patients, it can be hard to draw complete conclusions.

“Teasing out individual elements is always fraught, and it’s actually a mistake to think they are separate,” he explains. For example, while a scheme like CTF can suggest the participants seek further medical treatment, that still requires further action from groups that may feel marginalised from the health service for any number of reasons. “The best evidence shows a sports intervention in addition to what we term ‘treatment as usual’.”

Even with that caveat, an appraisal of CTF carried out in 2018 shows there are systemic improvements in the outcomes of the patients. People with serious mental health conditions are at a higher risk of dying from preventable lifestyle diseases such as diabetes, heart or liver disease due to lower physical activity levels or higher risk of alcohol, drug or smoking abuse. Some 80% of participants reported a reduction in drug consumption after taking part in CTF; on average, the patients doubled their weekly vigorous activity. There were significant gains in quality of life: 44% said they were feeling more positive generally, 67% reported an improvement in their relationships, and 63% said they felt a higher sense of achievement.

Welsh says the involvement of experts like Dr Mason and the support of occupational therapists from within the NHS have been integral in delivering the scheme, which in turn has led to further funding.

“It’s a combination of funding and then what I call the ‘clinical underpants’. They provide clinical governance, which makes this a mental health project. Because there are too many mental health and football projects which don’t really get to grips with that, and they’re driven by football outcomes.”

Welsh explains that the stripping of competition from the delivery of the programme is crucial to providing a space for treatment. As a former player himself—he was on the books at Middlesbrough and Peterborough United as a young goalkeeper, before becoming a coach at Arsenal and Tottenham’s academies—he says he was laser-focussed on winning. However, he is always steering the participants away from creating a team that could play in a league, as the added stress of competition could take away from the clinical aims of the project.

The Vault 027: Looking for Legends

One man’s quest to fulfil his childhood dreams…

“People might say something like ‘let’s start a mental health league. All that does is reinforce the stigma,” he says. “What we wanted to do was for people to feel normal again, that comes from the community, the continuity and the consistency of our delivery.”

The scheme also doesn’t attempt to replicate some of the less desirable aspects of “football culture”.

“If we mean that to be tough guys, beer drinking, and terrace chants, CTF is just not like that at all,” says Dr. Mason. “It’s very supportive, has a truly wide range of ethnicities, has some females attending (around 7% of participants are women and girls) and is firmly not about playing football to any standard.”

That doesn’t mean that needs to be the standard practice for all initiatives. Competition is not inherently antithetical to the use of sport as a means of improving mental health outcomes. Dr Opher says that for many, part of the appeal of attending a game is the chance to lose themselves in the atypical environment of the terraces.

The momentum behind social prescribing in the UK is growing, says Dr Opher. He reports the NHS has advised other nations on the tactic, while a delegation from Taiwan recently visited the National Association of Social Prescribers to learn more about how it can reduce stress on public health services.

“I did some primary research into this a few years ago,” he says. “Not only does it improve mental health scores, it does two other things.

“If you engage people in a social prescription, they’re less likely to come to the doctor, which is good, predominantly, because we can be quite dangerous as doctors. We can prescribe all manner of nasty drugs and investigations.

“There will be less use of emergency services, too. One of the problems of social isolation is, if you have a problem, there’s nobody to ask about it. The more you integrate people, the better, as it reduces the demands on emergency services.”

CTF’s 2018 study appears to back that idea up. They report that across the 72-person cohort, the total use of acute mental health bed days fell by 589 over a two-year period. The NELFT clinicians at every session help reduce reliance on acute care services by keeping people out of hospital. These therapeutic interventions are where the real savings occur.

All this mounting evidence proves that while football could become a popular tool within a wider mental health strategy, it is not a silver bullet. Those five-a-side sessions in Southwark helped me immensely, but the real change in my wellbeing didn’t come until I was seen for an ADHD assessment, I accessed talking therapies and was better able to express my feelings to my partner and the people around me.

However, for years, I allowed ill-defined and half-hearted suggestions from overworked healthcare professionals to ‘exercise’ and ‘socialise’ more to wash over me. Actively prescribing access to those spaces where people can act on that guidance without thinking about it or worrying about the costs is so valuable.

By speaking to these experts and people who have built space for people to enjoy this game, it confirms a nagging suspicion many of you probably share. That nebulous idea that football helps us all cope.

Playing and watching football has made me a more confident person. It’s provided a space for me to take out my frustrations on teammates, opponents and muggy little linesmen that don’t have a clue what they’re looking at. The first time I ever told one of my best mates about having a panic attack was outside Tottenham Hotspur Stadium; I don’t think I looked him in the eye once during the whole conversation, but something about the imminent prospect of 90 minutes on the terrace made it all feel so much easier. To know there’s some evidence that this game can really help people manage their mental health makes me feel less alone, a little less ‘crazy’.

So, who’s up for a kickabout on Monday?

*Quotes taken from a pseudonymised case study provided by LPFF.