In the Spring of 1994, Kurt Cobain, Courtney Love and Roddy Bottum hatched a secret plan. The trio, who had long before bonded over their shared addiction to heroin, made a pact to enter an LA rehab center so they could clean up once and for all. Only Bottum went through with it.

“We were all set to go,” he says. “Then the telephone rings and Courtney tells me plans have changed. She said, ‘we’re going up to Seattle. We’ve got a bunch of pills and we’re going to detox up there. Come up. We’ve got a plane ticket for you.’”

Bottum, then the keyboardist for the platinum selling band Faith No More, whose satirical lyrics and punishing beats fired grunge era hits like “Epic” and “Easy,” politely declined. “I already told my family I was going to go to rehab,” he says. “I had to stay that course.”

Weeks later, a still addicted Cobain ended his life, an act that remains one of the most shocking and consequential in rock history. “To this day, it still haunts me,” Bottum says. He remains just as unnerved by a phone conversation he had with Cobain after he began the rehab stint the others shunned. Half-way through the month-long program, Bottum told the Nirvana frontman, “I’m finally through with withdrawls. I’m getting clean. There are just two weeks left. Then Kurt said, ‘I always leave at that point.’ It felt like a sign from him saying ‘you should see this through because look at me.’ He was acknowledging that he couldn’t get out of it.”

Though Bottum could and did, the story of his life leading up to it shows how easily things could have gone a very different way. He’s finally telling that tale in a new memoir, titled The Royal We, that stands far apart from the usual trauma-to-triumph rock star redemption stories. The tone he takes in his writing – flip, blunt and utterly unrepentant – captures the unmistakable voice of an accomplished provocateur. “Offensive things attracted us most,” he writes of his kind. “Upsetting people felt important.”

The handlebar moustache, the short-cropped hair, the flannel shirt, the tight jeans, all of the gay men wore that. I for sure didn’t want to be part of that

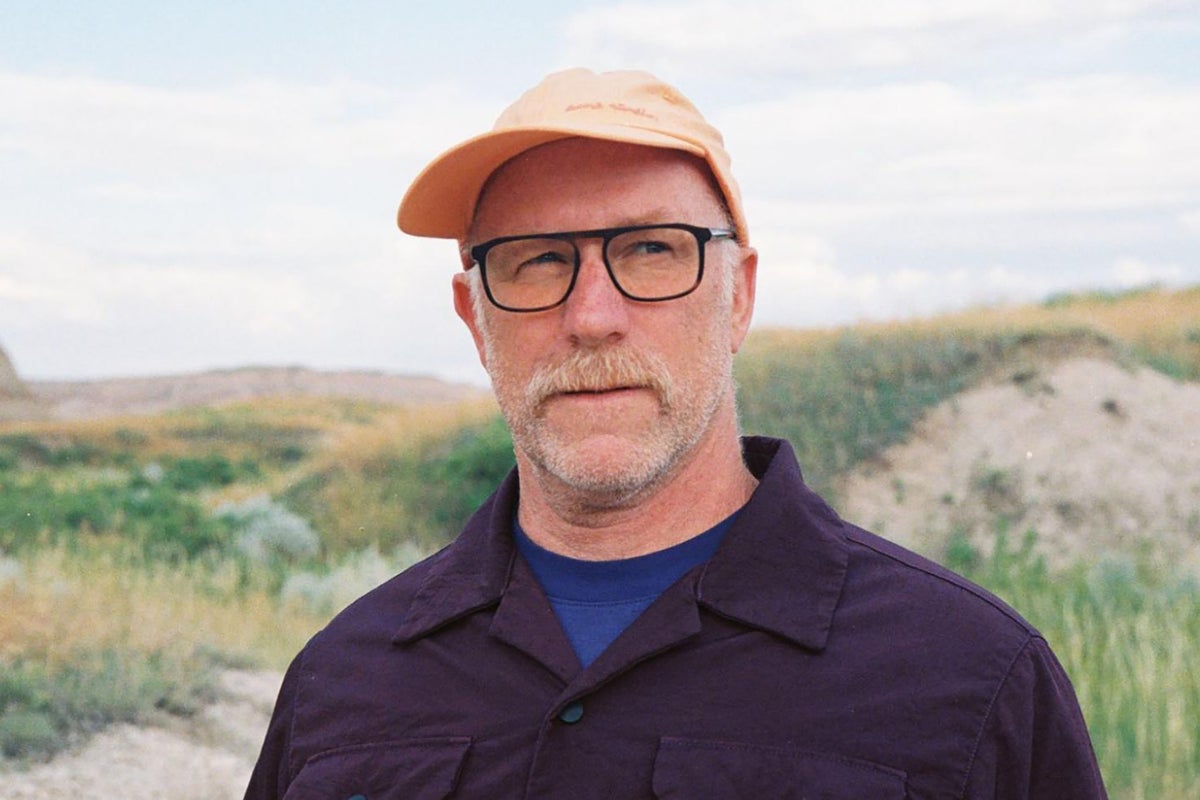

It also felt powerful, providing him with a strategy to survive the era he grew up in. Born in 1963, the now 62-year-old Bottum was barely a teen when he knew he was gay; this at a time when that identity was almost universally seen as a sickness worthy of the most venomous contempt. “I learned to diligently detest who I was,” Bottum writes.

At the same time, he dove into gay sex with abandon. By 14, he was reveling in glory holes and al fresco encounters, always with men far older than himself, something he feels zero regret or shame for. “I’d do it all over again in a heartbeat,” he writes. Even in church, he fantasized about gay sex. “All I wanted was to be molested by a priest,” he writes, a line he tells me he fervently hopes will upset as many people as possible. “I’m happy to cause shock waves,” he tells me with a smile. “I have some Christian family in the Midwest and I’m sure it will come around that Roddy has written a book. I can’t wait to ruin their holiday!”

Pointed as that may sound, Bottum has a soft edge when we talk. Speaking by Zoom from an apartment he rented in Paris to attend Art Basel (normally, he lives in New York), he exudes a calm that stands in striking contrast to the willful chaos he chronicles in his book. Some of that may reflect the grounding he received from his family, who were always cool with even his most extreme quirks. When he began drinking and doing drugs in his early teens, it wasn’t them he was rebelling against; instead it was the world that made being gay something to be buried in the deepest recesses of the mind. The drugs, which he used to numb the judgement, became one more thing to hide. “There were so many secrets I was keeping,” he says.

open image in gallery

Bottum (far right) as part of Faith No More in 1990 (Ebet Roberts/Getty)

Having little interest in school, Bottum moved to San Francisco at 17, where his instinct for insurrection made it easy for him to find other strays and malcontents. “I’d find overlooked and discarded things and make them my friends,” he writes. “We made it a point to not belong.” The rough and tumble San Francisco of the era was ideal for that. “It’s a hardship for those of us who lived through those glory days to witness what San Francisco has become,” he says, “with the tech bros and the strollers and the drunk girls.” Of course, when he arrived in the city it also was perhaps the most accepting place on the planet for gay people. Even so, Bottum didn’t come out then. “It seemed too obvious,” he says, a cardinal sin for someone of his contrarian nature. Worse, he found the city’s gay scene even more conforming than the straight one. Within that demi mode, the “clone look” ruled. “The handlebar moustache, the short-cropped hair, the flannel shirt, the tight jeans, all of the gay men wore that,” Bottum says. “I for sure didn’t want to be part of that.”

In defiance, he dove into the rock scene which, at the time, was totally straight identified, a reality he felt delayed his self-acceptance even longer. Though his bandmates knew of his sexuality, they seldom talked about it. “For the guys in Faith No More, it was easier to ignore that I was gay and, given that, it was easier for me to ignore it too,” he says. To add to the irony, Bottom had a boyfriend at the time – the band knew him well, but also despised him. In fact, most people despised him, a major plus for Bottum, who admits to being attracted to him, in part, because of his obvious mental issues. “I was in love with a sickness,” he writes.

open image in gallery

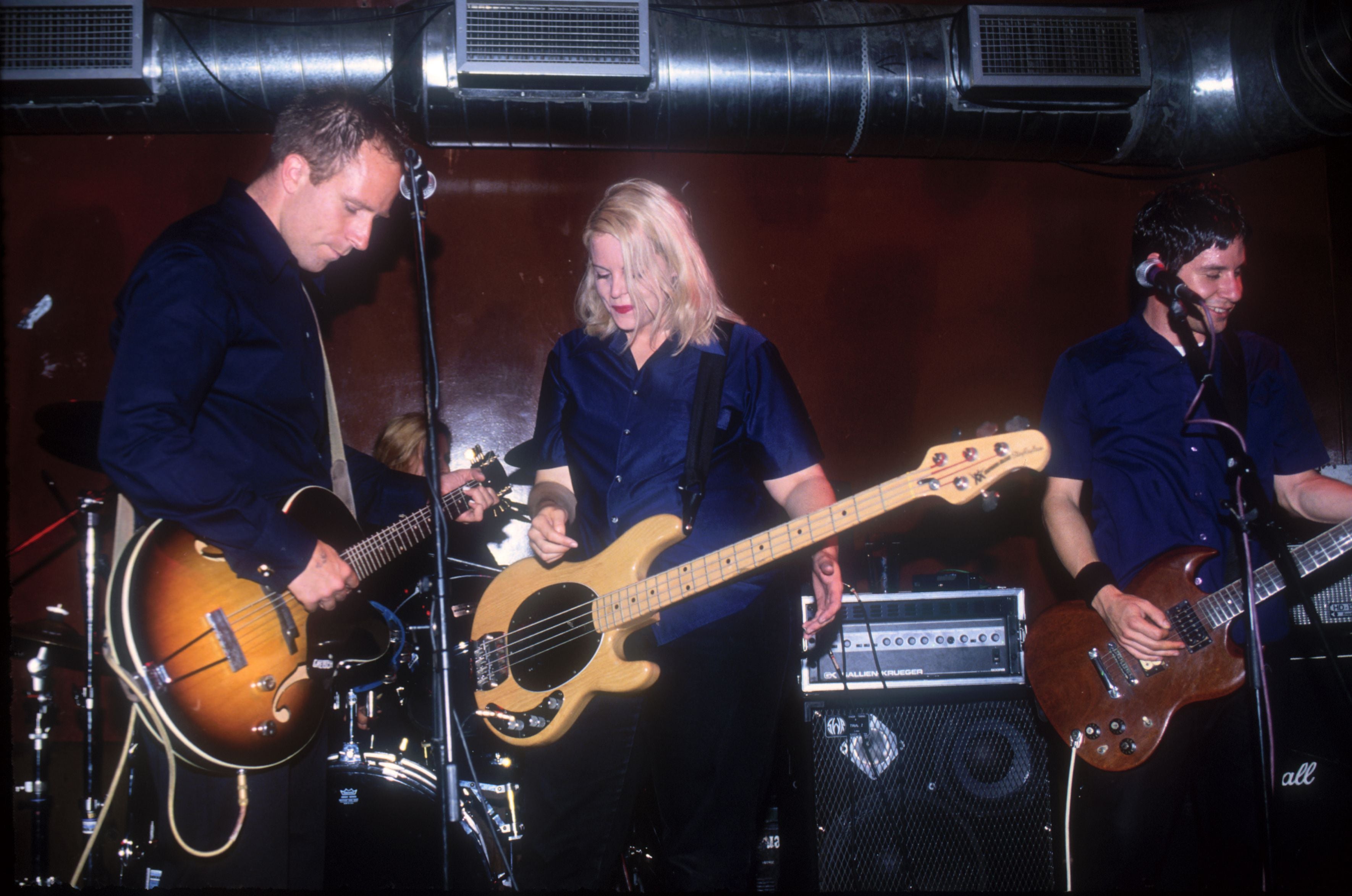

Bottum with his Imperial Teen bandmate Lynn Perko-Truell in 1996 (Andre Csillag/Shutterstock)

A similar dynamic attracted him to Love, who he adored even as he saw her burn through friend after friend, who all got fed up with her loudness, her thirst for attention, and her ease with lying. When they first met, Love told Bottum they were born on the same day, a flagrant fib he didn’t discover until five years later. “I was so impressed by that trickery,” he says. He loved, too, the mania she created. In the book he likens her to “a person with too many arms”. Emboldened by a seemingly boundless capacity for chutzpah, Love essentially hired herself to serve as Faith No More’s frontperson for a short while. In that time frame, her relationship with Bottom turned sexual, even though she knew he was gay. “It felt insanely open minded at the time,” he says with a laugh.

At one point in their brief affair, Bottum writes that Love became pregnant and had an abortion, something he believes she has never discussed in public. Stated in his book as well is the assertion that Love was briefly married to a guy in Los Angeles, a relationship so odd and doomed that, on their wedding night, she and Bottum did heroin on the bed the newlyweds shared. Bottum, who remains close with Love, says she raised no objections about its contents. In fact, she offered a glowing blurb on the back cover. (Reached separately, Love’s assistant confirmed the abortion and the marriage, while adding that the later was annulled for “non-consummation.”)

When Love became involved with Cobain, they and Bottum formed a kind of drugged out “throuple.” In his book, Bottum writes that Cobain “loved that I was gay because he wanted to be”. Of course, wanting to be gay, but not being able to, may be the most surefire sign of straightness ever, a view Bottum grinningly acknowledges. More broadly, he believes Cobain simply admired his role as an unassailable outsider, an identity the Nirvana leader co-opted by writing the highly subversive line, “everyone is gay,” in his song “All Apologies.”

open image in gallery

Faith No More performs in 2015 (Getty)

Ironically, Bottum was still in a kind of identity limbo then. He was openly gay to many but closeted, in key ways, to himself. His road to publicly coming out had a strange origin. At the platinum-selling height of their fame, Faith No More opened a tour for Guns N Roses, on which they found themselves immersed in a world of “male hetero aggression,” Bottum says. “That insane misogynistic behavior is so not who I was. One way of separating myself from all that was to say, ‘oh, by the way, I’m gay.’”

He did so in a major interview for the LGBTQ magazine The Advocate in 1993, making him one of the first out rock stars. However, when he did the interview he was high on heroin, certifying his lingering ambivalence. At the time, heroin was everywhere on the scene, aided, Bottum believes, by the glow of Cobain and Love’s usage at the height of their fame. “It was as if the drug had hired a PR firm,” Bottum writes. Tragically, he says, Cobain didn’t have the inner strength to survive it all. “He was really fragile in a way that Courtney could never be,” he says.

Bottum’s own turnaround may have begun in rehab, but it didn’t come to full fruition until a trilogy of deaths encircled him. At nearly the same time as Cobain’s suicide, Bottum lost his father and a close friend from rehab, turbo-charging his resolve to come out on every level. He did so most decisively in 1996 by forming the band Imperial Teen, where he became the frontman, singing lyrics that spoke pointedly of gay life and desire. “The opportunity to be able to sing lyrics from the heart with no shame was a real game changer for me,” he says.

open image in gallery

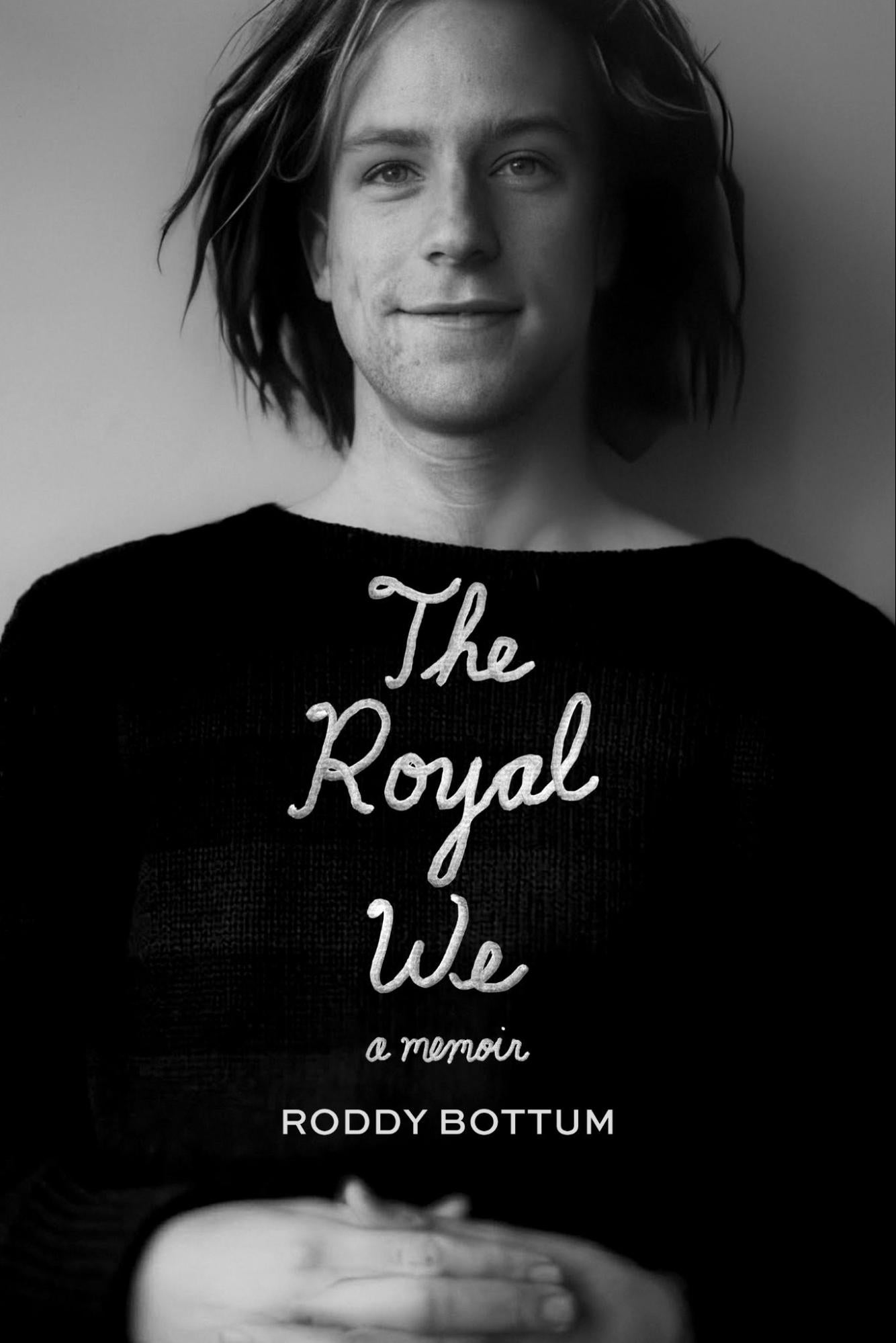

‘The Royal We’ by Roddy Bottum (Jawbone Press)

At the same time, Bottum makes clear in the book that any sense of closure is, for him, a myth. All these years later, he says, he still hasn’t fully processed Cobain’s suicide. “I’m always trying to figure it out,” he says. “What’s the reason? The truth is, not every question gets answered.” The closest he can come is focusing on Cobain’s “mental illness,” he says. “It wasn’t acknowledged then the way it would be now. Today, a person like Kurt would be on meds a lot sooner.”

Likewise, Bottum believes his own path to self-acceptance would have arrived much sooner if he were coming up today. “There is a sense of lost time because of that,” he says. “I see kids now who are so open about their queerness from an early age and I’m kinda jealous.”

At the same time, he has come to embrace his story as it actually occurred. “Having gone through the hardship of being judged and hiding things and finally accepting it all has made me a really strong person,” he says. “In the end, it all came together pretty poetically.”

‘The Royal We’ is out now, via Jawbone Press