Astronomers have discovered a superheated “star factory” that existed just 800 million years after the Big Bang. The star factory, a galaxy known as Y1, is birthing stars at a rate 180 times faster than the Milky Way does. The discovery of such a previously unknown extreme region of starbirth could help scientists explain how galaxies grew so quickly in the early universe.

The team discovered the nature of Y1 by first measuring the temperature of its superheated cosmic dust. Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), the researchers were able to analyze the light emitted by the primordial galaxy, which has been travelling to Earth for 13 billion years.

You may like

The research is part of a continuing effort by astronomers to understand the conditions under which the first generation of stars, known as “Population III (POP III)” stars, formed. These conditions are thought to be very different from the conditions under which modern, or POP I, stars like the sun were born.

Touring star factories

Stars are forged in vast complexes of dense gas and dust such as the Orion Nebula and the Carina Nebula in the local universe. These nebulas are bright because their star-forming gas and dust is illuminated by light from young massive stars within them. This illumination covers both light visible to the human eye and longer wavelengths of light in the infrared and radio regions of the electromagnetic spectrum.

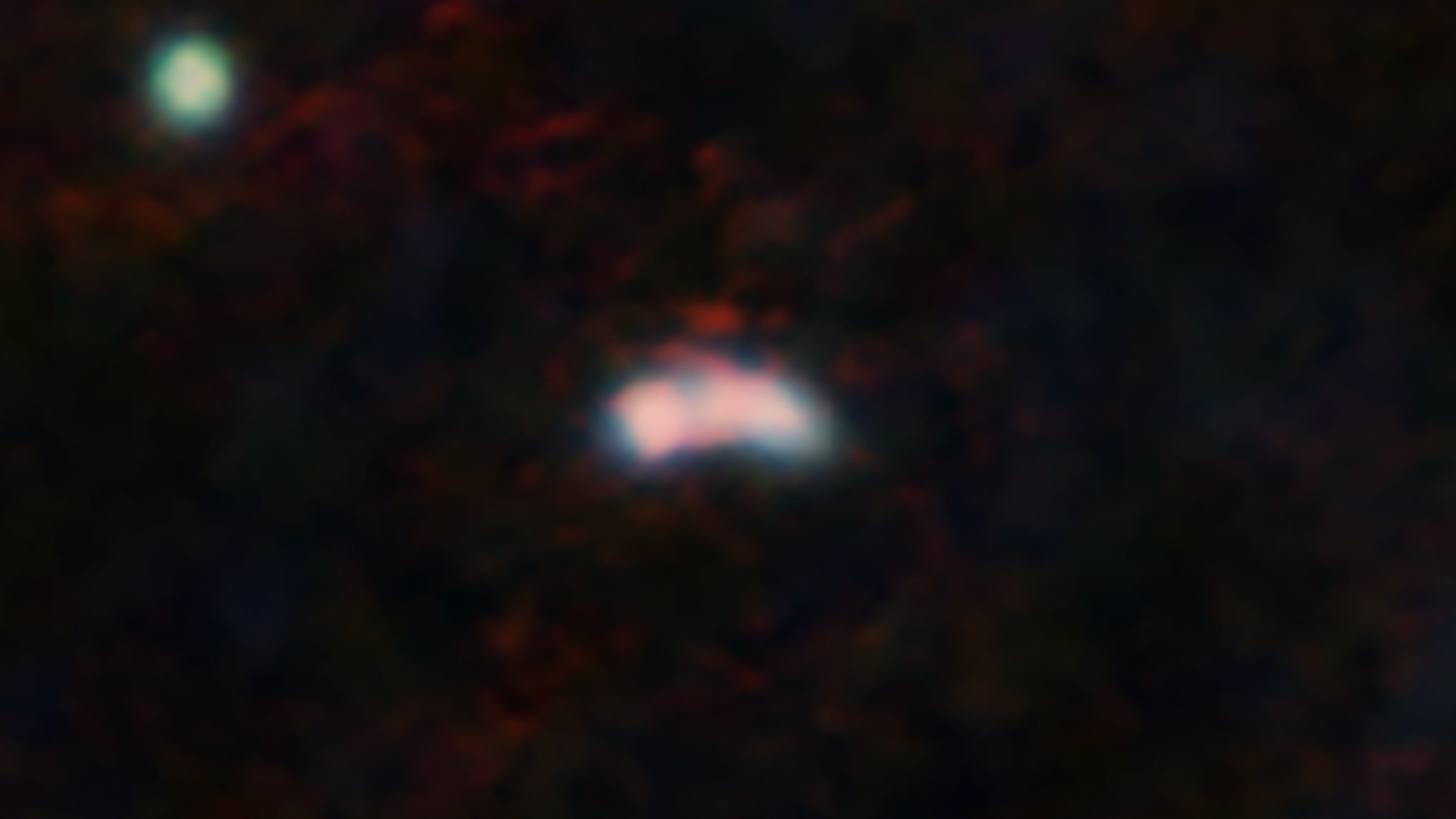

“At wavelengths like this, the galaxy is lit up by billowing clouds of glowing dust grains,” Bakx said. “When we saw how bright this galaxy shines compared to other wavelengths, we immediately knew we were looking at something truly special.”

This revelation was possible thanks to the sensitivity of ALMA, composed of 66 radio antennas located in the Atacama desert region of Northern Chile, and its Band 9 instrument which is tuned to a specific wavelength of light. ALMA allowed Bakx and colleagues to determine that the dust of Y1 was glowing with a temperature of around minus 356 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 180 degrees Celsius).

“The temperature is certainly chilly compared to household dust on Earth, but it’s much warmer than any other comparable galaxy we’ve seen,” team member Yoichi Tamura of Nagoya University in Japan said. “This confirmed that it really is an extreme star factory. Even though it’s the first time we’ve seen a galaxy like this, we think that there could be many more out there. Star factories like Y1 could have been common in the early universe.”

While Y1 is producing stars and growing at an incredible rate of around 180 solar masses every year as the team observed it 13 billion years ago, this starburst period wouldn’t have lasted too long, at least not in cosmological terms. Scientists do theorize, however, that these periods of intense star formation or starburst may have been common in early galaxies, but are currently hidden from our view.

“We don’t know how common such phases might be in the early universe, so in the future we want to look for more examples of star factories like this,” Bakx said. “We also plan to use the high-resolution capabilities of ALMA to take a closer look at how this galaxy works.”

You may like

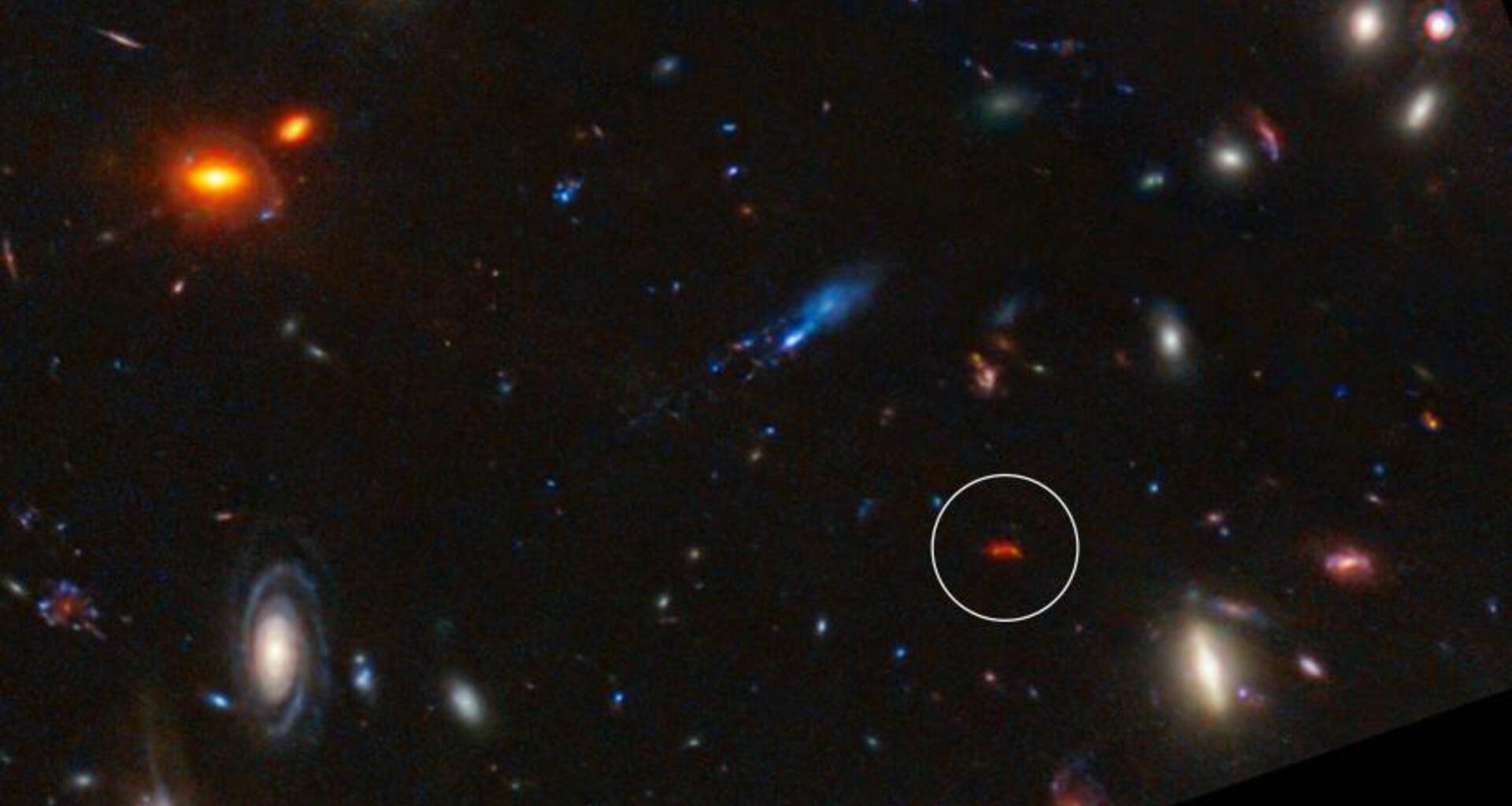

Galaxy Y1 and its surroundings as seen by the James Webb Space Telescope’s NIRCAM (blue and green) and by ALMA (red). (Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA (JWST), T. Bakx/ALMA (ESO/NRAO/NAOJ))

Further investigation of Y1 may help answer a lingering puzzle about galaxies in the early universe. Previous studies have shown that primordial galaxies are filled with more dust than their older population of stars can create. The relatively high temperature of Y1 could pose an answer to this puzzle, suggesting that the high volume of dust is actually an illusion.

“Galaxies in the early universe seem to be too young for the amount of dust they contain. That’s strange, because they don’t have enough old stars, around which most dust grains are created,” team member Laura Sommovigo, of the Flatiron Institute and Columbia University said. “But a small amount of warm dust can be just as bright as large amounts of cool dust, and that’s exactly what we’re seeing in Y1.

“Even though these galaxies are still young and don’t yet contain much heavy elements or dust, what they do have is both hot and bright.”

The team’s research was published on Wednesday (Nov.12) in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.