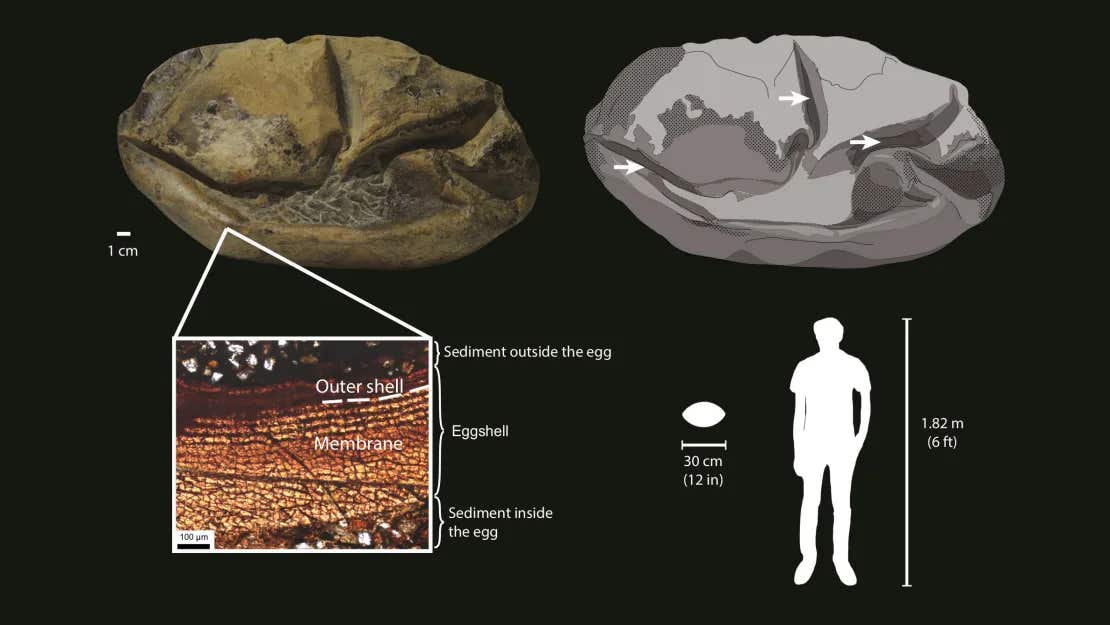

A leathery fossil unearthed from Antarctic sediment is overturning core ideas about how Earth’s dominant marine reptiles reproduced during the Late Cretaceous. Measuring about 11 by 8 inches and dating back 68 million years, the egg—identified as Antarcticoolithus bradyi—is the largest soft-shelled egg ever found and the second-largest egg of any known species.

Discovered in 2011 on Seymour Island, the object puzzled scientists for years. Its structure didn’t match any known fossil category. It looked more like a deflated balloon than a traditional egg. Only after nearly a decade of analysis was its true nature confirmed: a soft-shelled egg likely laid by a large marine reptile, perhaps a mosasaur.

An artist’s rendering of a pair of mosasaurs and their egg. CREDIT: Francisco Hueichaleo

An artist’s rendering of a pair of mosasaurs and their egg. CREDIT: Francisco Hueichaleo

This fossil has triggered a significant shift in how paleontologists view reproductive behavior in ancient marine reptiles. The egg’s thin, flexible shell—resembling those of modern snakes and lizards—suggests that some marine reptiles may not have given birth to live young, as long believed, but instead laid soft-shelled eggs directly into the ocean. That possibility was once unthinkable for animals of such scale.

A Mosasaur Candidate Emerges

Close to the fossil egg, researchers found the skeletal remains of Kaikaifilu hervei, a massive species of mosasaur that swam Antarctic waters near the end of the dinosaur age. The egg’s size and proximity to the remains suggest a likely connection. Additional nearby fossils of juvenile mosasaurs and plesiosaurs bolster the idea that the area once functioned as a marine reptile nursery.

Lucas Legendre, lead author of the research and postdoctoral fellow at the University of Texas at Austin, said the egg is “from an animal the size of a large dinosaur, but it is completely unlike a dinosaur egg.” Its papery shell and lack of pores make it more similar to the reproductive traits of modern lizards and snakes.

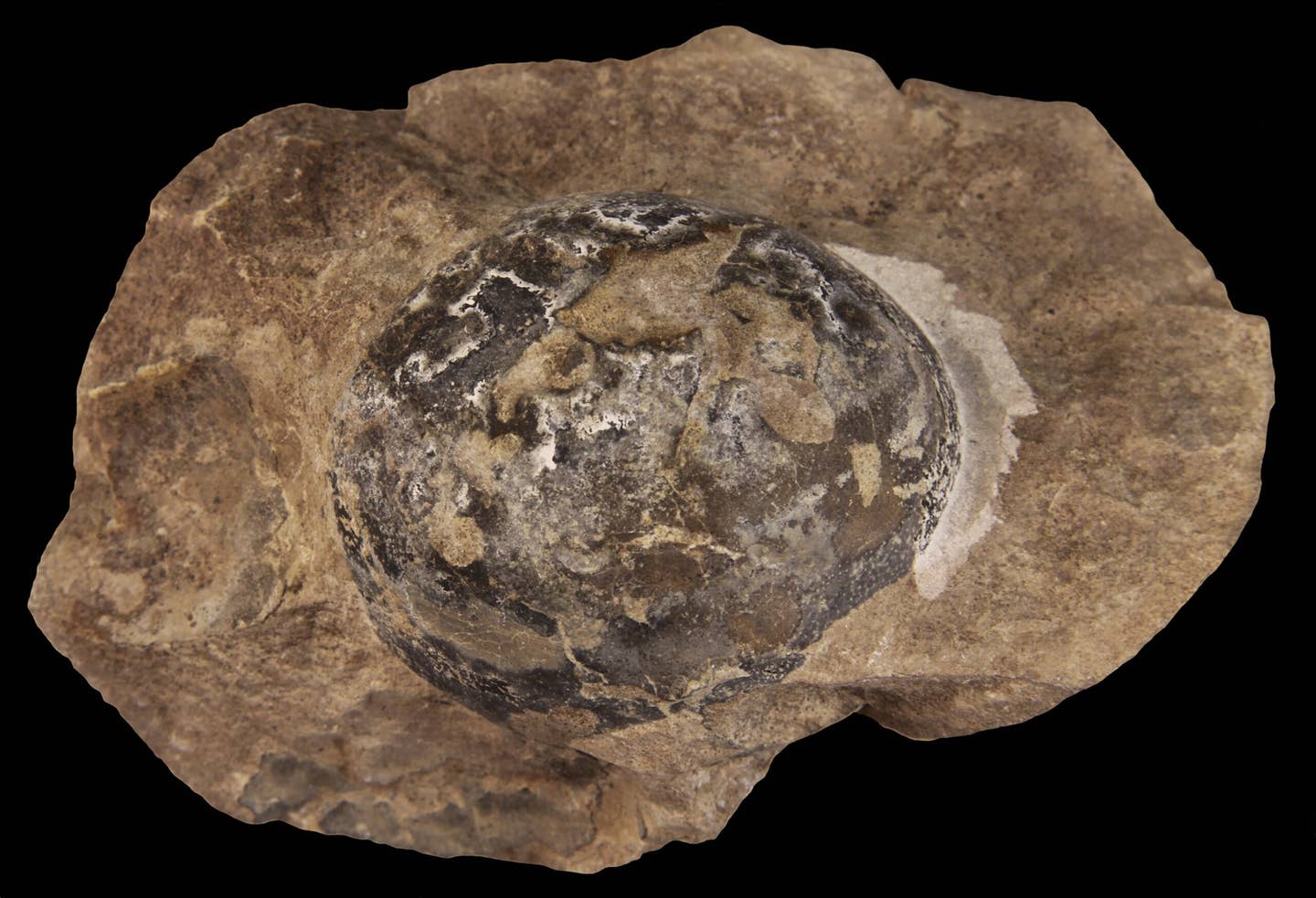

This fossilized egg was laid by Mussaurus, a long-necked, plant-eating dinosaur that grew to 20 feet in length. CREDIT: Diego Pol

This fossilized egg was laid by Mussaurus, a long-necked, plant-eating dinosaur that grew to 20 feet in length. CREDIT: Diego Pol

Julia Clarke, a vertebrate paleontologist at UT Austin and co-author of the study, described it as “exceptional in both size and structure.” The team’s findings, published in Nature, support the hypothesis that some large marine reptiles laid aquatic eggs that hatched almost immediately—a strategy still seen today in some sea snakes.

An independent summary by The Brighter Side of News confirmed that analysis of 259 modern reptile species placed the potential mother’s body length at over 23 feet, excluding the tail—consistent with known mosasaur dimensions.

Redefining the Egg: Soft Shells in Deep Time

The Antarctic discovery adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that soft-shelled eggs were far more common among ancient reptiles than previously recognized. For decades, hard-shelled eggs dominated the fossil record due to their durability. That visibility may have biased scientific models toward thinking they were the standard.

A diagram showing the Antarcticoolithus bradyi egg, its parts and size relative to an adult human. CREDIT: Legendre et al

A diagram showing the Antarcticoolithus bradyi egg, its parts and size relative to an adult human. CREDIT: Legendre et al

Recent discoveries of soft-shelled eggs in species like Protoceratops and Mussaurus suggest otherwise. Darla Zelenitsky, a paleobiologist specializing in fossil eggs, called the Antarctic find “pretty spectacular.” She noted its importance in uncovering how soft-shelled egg fossils could alter our understanding of early reptile evolution.

Hard-shelled dinosaur eggs were once assumed to be ancestral. But these new fossils point to the reverse: soft shells may have come first, with hard shells evolving independently in different lineages. Mark Norell, chair of paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History, explained, “The assumption has always been that the ancestral dinosaur egg was hard-shelled. These findings prove otherwise.”

Antarctica’s Hidden Fossil Potential

What’s perhaps most unexpected is that such a fragile object fossilized at all—especially in the extreme conditions of Antarctica. The egg’s preservation suggests sediment and climate conditions ideal for fossilizing soft tissues, which typically degrade before they can be preserved.

Well-preserved Protoceratops embryos included six nearly complete skeletons. CREDIT: M. Ellison/AMNH

Well-preserved Protoceratops embryos included six nearly complete skeletons. CREDIT: M. Ellison/AMNH

This makes Antarctica an increasingly important site in global paleontological research. Its potential to reveal new fossils—not just of bones, but of delicate biological structures like eggs—is now clear. Scientists involved in the A. bradyi study are planning further expeditions to explore the surrounding regions.

The hope is to determine how widespread this reproductive behavior was, and whether other marine reptiles, including plesiosaurs, used similar strategies. The fossil also invites closer study of sediment types and fossilization patterns in cold climates, which may preserve delicate remains better than previously assumed.