Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Alicja Ptak

The article is part of a new series by Alicja Ptak, senior editor at Notes from Poland, exploring the forces shaping Poland’s economy, businesses and energy transition. Each instalment will be accompanied by an audio version and an in-depth conversation with a leading expert on The Warsaw Wire podcast.

You can listen to this article and the full podcast conversation on Spotify, Apple Podcasts and YouTube.

On 23 December 2019, then-Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki handed Poles an early Christmas present, announcing what he called a historic moment for Poland’s public finances.

For the first time in the country’s post-communist history, the budget for the coming year would be balanced. In 2020, the state was supposed to spend no more than it raised.

Morawiecki, not known for his rhetorical flourish, recited in a monotone list everything Poland would still be able to afford: child benefits, tax exemptions for young adults, lower income tax for other workers, and additional pension payments. All this, he stressed, despite global uncertainties – Brexit, a Eurozone slowdown, and US-China trade tensions.

“Our public finances have probably never been in such good shape,” he said.

Readers in 2025 may allow themselves a wry smile. Just days later, Chinese health authorities would report 27 cases of an unexplained pneumonia in Wuhan – the spark of a pandemic that would shut down the world and force governments, including Morawiecki’s, to issue unprecedented amounts of debt to keep their economies alive.

As a result, the 2020 budget was anything but balanced. Poland ended the year 85 billion zloty (€20 billion) in the red, the deepest deficit since the country revalued its currency in 1995.

The shortfall narrowed over the next two years, but 2022 brought another “black swan” event: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, triggering an energy crisis and a dramatic increase in defence spending. The deficit surged again, reaching nearly 211 billion zloty last year.

After taking into account non-budgetary debt, including that incurred by local governments, the deficit reached nearly 240 billion zloty.

This year, with two months still to go, Poland has already exceeded last year’s record – the budgetary deficit at the end of October stood at almost 230 billion zloty.

A country once praised for its fiscal discipline has suddenly found itself under far closer scrutiny. The European Union placed Poland under its excessive deficit procedure, demanding steps to rein in spending and debt.

Yet despite these obligations, Poland’s spiralling public debt shows little sign of slowing down: in the second quarter of 2025, it grew at the second-fastest annual rate in the EU.

Poland has recorded the EU’s second-fastest annual increase in public debt, new @EU_Eurostat data show.

The country has been running sizeable budget deficits in recent years as it boosts social spending and ramps up defence investment https://t.co/jjEqAJALl8

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 23, 2025

At this point, some nuance is needed. While Poland’s debt has been growing rapidly, its overall size, as a share of GDP, is far from catastrophic.

In the second quarter of this year, its debt – including off-budget borrowing, a measure tracked by the EU – stood at 58% of GDP. That is below the EU’s 60% ceiling, well under the bloc’s average of 82%, and far from levels seen in Greece (151%), Italy (138%) and France (116%).

Which raises the question: how big a problem is Poland’s swelling public debt, really? According to analysts, the issue is two-fold.

First, the problem is less the current level of debt than where it is heading. Second, the chances of reversing that trajectory appear slim, as public finances have become hostage to a political tug-of-war between the broad governing coalition that replaced Morawiecki’s government in 2023 and opposition-backed President Karol Nawrocki.

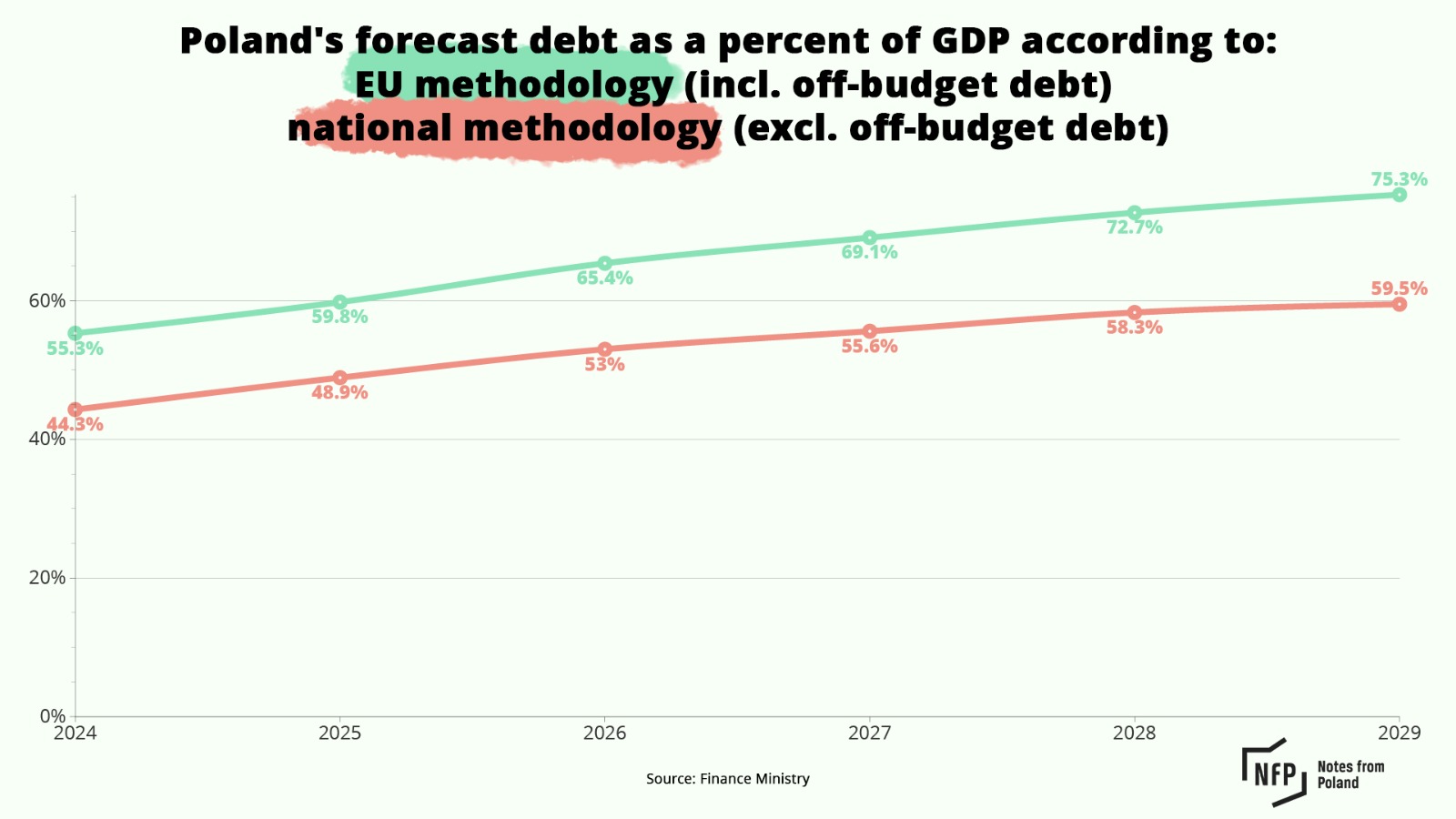

According to the finance ministry’s debt management strategy published in September, the rise will continue in the following years. By 2029, Polish debt is projected to reach 75% of GDP.

However, Aleksander Kieroński, an analyst at Polityka Insight, warns that the headline debt ratio is not the most urgent concern. “It’s the cost of servicing it that should worry us – and it is rising in Poland,” he told me on a recent episode of the Warsaw Wire podcast.

“We are issuing more debt to refinance the old debt, and this new debt is much more expensive than the old one. This is what’s dangerous. This is what actually causes the crisis of public finance – not the level itself.”

The ministry expects debt-servicing costs to rise from 1.9% of GDP today to 2.6–2.7% in 2029. With the Polish economy set to surpass the $1 trillion mark this year, becoming the world’s 20th-largest economy, annual interest payments could exceed $27 billion within four years.

Slowing this trajectory would require reducing deficits – either by cutting spending or raising revenue. Both paths are politically fraught, especially for a government struggling in the polls just two years before the next parliamentary election.

And both paths are also likely to be blocked in practice.

“No matter what the government tries, whether it is on the revenue side or on the expenditure side…it is very likely that this will be vetoed by the new president,” Milan Trajkovic, Poland’s primary analyst at Fitch Ratings – the agency that recently revised Poland’s outlook to negative in response to the accelerating debt trend – told Notes from Poland.

Credit ratings agency Fitch has revised Poland’s outlook to negative, citing “deteriorating public finances” and “political polarisation”.

The finance minister blamed the opposition-aligned president. But the opposition says the government is responsible https://t.co/tQ6fh3hWZS

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) September 6, 2025

During his campaign, Nawrocki pledged to oppose any bill that raises taxes or introduces new fiscal burdens – a promise made during an appearance on a YouTube programme hosted by far-right, libertarian politician Sławomir Mentzen, as Nawrocki desperately sought to win over Mentzen’s supporters in the second-round run-off.

However, recent events suggest the president’s stance on new taxes may be more nuanced in practice. This week, for instance, he signed a bill raising corporate income tax for banks but vetoed another that would have increased taxes for family foundations.

Nawrocki justified signing the bank tax increase by saying it was unacceptable for ordinary citizens and small businesses to shoulder the tax burden while large financial institutions posted record profits.

Meanwhile, he argued that his opposition to taxing family foundations – typically used by wealthy families to protect intergenerational assets – stems from a desire to uphold “the agreement the state made with Poles when it introduced” such foundations in 2023 under the former government

President @NawrockiKn has signed into law a government bill increasing the corporate income tax rate for banks in Poland.

The measure will provide billions in revenue at a time when Poland is seeking to tackle rapidly rising public debt https://t.co/ZmOCEcvvIj

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) November 27, 2025

Reducing expenditure poses similar challenges. Both analysts – who spoke to the Warsaw Wire before Nawrocki’s decisions – emphasise that, contrary to popular belief, it is not defence spending that has driven the deficit, but social spending, which has ballooned in recent years.

“Defence spending accounts for about one quarter, maximum one-third, of this deterioration in public finances. Two-thirds to three-quarters is the increase in public wages, social benefits and the introduction of new social benefit programmes,” says Trajkovic. “When you compare Poland with other Central and Eastern European countries, the increase in those expenditures is one of the highest.”

Kieroński notes that attempts to scale back benefits would be met with fierce political resistance. Limiting the popular 800-zloty-per-month child benefit to lower-income families, for instance, could save billions zloty a year, he says.

The richest 20% of households in Poland receive more in child benefits than the poorest 20%, a new report has found.

Its authors recommend that the government move away from universal benefits and instead direct support towards those who need it most https://t.co/vMiKdzh9bJ

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) November 28, 2025

A recent study by the Centre for Economic Analysis (CenEA), a think tank, shows that this year the richest 20% of households will actually receive more in child benefits – about 12.9 billion zloty – than the 12.6 billion zloty paid out to the poorest 20% of households.

Restricting 800+ only to less affluent households “would actually be quite beneficial for our economy and for our budget,” says Kieroński. But it would probably be a “political suicide”, he adds.

For now, strong growth provides a buffer. But, Kieroński warns, relying solely on economic expansion and hoping for no further shocks is not a strategy.

“We have to manage our public finances. Without doing so, we’re driving toward a wall,” he said, adding that the consequences are likely to fall not on the current government but on the next one.

Poland has emerged as Europe’s undisputed growth champion over the past 35 years.

In the first part of a new series of articles and podcasts, @AlicjaPtak4 explores the reasons behind Poland’s rapid economic development, and the dangers that may lie ahead https://t.co/bW3bnV7Ozn

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) July 7, 2025

When asked whether rising debt now threatens Poland’s economy, analysts say it does not – at least not yet. Demand for Polish bonds remains strong, meaning investors are still keen on buying Polish debt, and most of it is issued domestically and denominated in zloty, reducing exchange risk.

The real economic pain would come later, when fiscal consolidation becomes unavoidable. “When you raise VAT…it hurts growth. When you raise personal or corporate income tax, or when you cut spending, it hurts growth,” says Trajkovic.

Still, neither analyst expects a market panic in the near term. Investors, Trajkovic notes, continue to view Poland as relatively stable compared with many indebted EU economies.

But his colleague, Erich Arispe, head of Eastern Europe at Fitch, is watching one more indicator closely: the debt level calculated under Poland’s national methodology, which – unlike the EU measure – excludes some off-budget borrowing.

In the second quarter, the figure stood at 47.1% of GDP. When it reaches the constitutional limit of 60%, politics may collide with hard law, and Arispe says it will be interesting to see “whether politics will prevail or if there is some actual compromise that can be found”.

The situation around debt “is a test for politicians”, says Kieroński. While it is “not yet that dangerous”, it could become a serious threat to the economy within five to ten years.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Jakub Żerdzicki/Unsplash

Alicja Ptak is senior editor at Notes from Poland and a multimedia journalist. She previously worked for Reuters.