He was on the verge of becoming the third Spanish Nobel Prize winner in science, after Santiago Ramón y Cajal and Severo Ochoa. But the Madrid-born biochemist Pedro Cuatrecasas died of cancer on March 19 at the age of 88 in La Jolla, California, and no obituary was published in any news outlet — not in his beloved homeland and not in his adopted country. Hardly anyone knows of Cuatrecasas’ existence, yet it would be hard to pick a person at random who hasn’t somehow benefited from his tremendous body of work. The researcher participated in the development of some 40 drugs, some of them well-known, such as acyclovir for herpes; sumatriptan for migraines; and atorvastatin, a cholesterol-lowering molecule that became the best-selling drug in history.

Cuatrecasas was born in Madrid on September 27, 1936, in the midst of the Spanish Civil War, as the fascists were advancing toward the capital. His father, a sympathizer of the Republican Left, was one of Spain’s most renowned scientists: José Cuatrecasas, director of the Royal Botanical Gardens until the coup’s victory forced him to flee with his family to the Americas. The boy grew up in exile in Colombia until his father found work in the United States in 1947. There, Pedro Cuatrecasas studied medicine and it soon became clear that he was Nobel Prize material.

“Pedro was absolutely brilliant,” recalls U.S. physician Peter Agre, winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2003 for discovering the pores that allow water molecules to pass through cells, giving rise to sweat and tears. Agre, 12 years his junior, joined Cuatrecasas’s laboratory at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore in 1973. He found a charismatic scientist, “gifted with enormous intelligence” and “extremely competitive.”

In 1968, at just 32 years old, Cuatrecasas and another colleague revolutionized biology and medicine with an eight-page study in which they invented a new technique for capturing specific molecules in a mixture of substances: affinity chromatography. The tool made it possible to easily purify hormones, antibodies, proteins and DNA. “There were rumors in the lab that Pedro could be the next Nobel Prize winner. If he had received it, he would have been hailed in Spain as a national hero, like Santiago Ramón y Cajal and Severo Ochoa,” says Agre.

The biochemist Pedro Cuatrecasas, at his home in La Jolla (California), in 2014.Colección familiar

The biochemist Pedro Cuatrecasas, at his home in La Jolla (California), in 2014.Colección familiar

Cuatrecasas had previously trained at the National Institutes of Health in the United States, under Christian Anfinsen, who also won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1972 after demonstrating that the sequence of a protein’s components determines its three-dimensional structure and function. In Anfinsen’s laboratory, the Spanish son of Civil War exiles met the Polish scientist Meir Wilchek, a Jew who fled the Nazis after his father was murdered at the Flossenbürg concentration camp. The two former refugees, then in their thirties, conceived the revolutionary affinity chromatography together, but added their boss as a third co-author out of courtesy.

“Pedro was very honest; he insisted on having Anfinsen sign the study,” recalls Wilchek, who is about to turn 90. “When we published it, it revolutionized the world of biology, biochemistry, and many other fields, because what had required months or years of work could now be done in a few hours. The method remains the most useful for purifying the molecules of living beings,” the researcher emphasized via email, just days after Iran bombed the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, where he has spent half his life.

In 1987, Wilchek and Cuatrecasas won the Wolf Prize, considered a precursor to the Nobel Prize. The award statement applauded their invention with a resounding statement: “Few if any other new techniques have so markedly and rapidly affected the growth of biomedical sciences.” The award highlighted that the tool could also be used to diagnose diseases and develop treatments. Cuatrecasas himself had used it to purify crucial molecules, such as the cellular receptors for insulin and estrogen, implicated in diabetes and breast cancer, respectively.

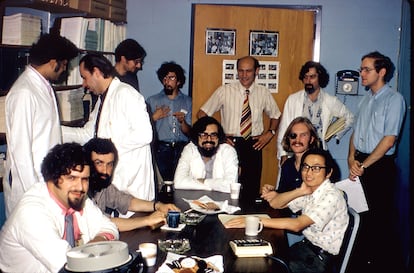

The laboratory of Pedro Cuatrecasas (in a striped tie) at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore around 1974. Peter Agre is the blond man with an eye patch. Colección de Peter Agre

The laboratory of Pedro Cuatrecasas (in a striped tie) at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore around 1974. Peter Agre is the blond man with an eye patch. Colección de Peter Agre

“We were nominated many times for the Nobel Prize,” Wilchek recalls. “Peter was a modest person. He didn’t give himself enough publicity, just like me, and that may be one of the reasons why we didn’t win the Nobel,” says the Polish scientist, who is still eligible for the award. The Swedish prize, however, is not awarded posthumously. “One day I met a member of the Nobel committee, and he told me we would never win it because Anfinsen was one of the signatories of our study and he had already received the prize for other research,” says Wilchek.

Cuatrecasas considered himself both Spanish and American until his death, his son Paul explains over the phone. “My grandparents always had typical Spanish food at their house in Washington: chorizo, anchovies… And my father returned to Spain once a year,” he recalls. On those trips, Pedro would visit his brother Gil, an abstract expressionist painter who decided to leave Washington, where he was an acclaimed artist, to move to Barcelona and disappear from public life. When Gil died of prostate cancer in 2004, Pedro found 400 of the artist’s monumental canvases that had been kept in storage for decades.

On June 19, exactly three months after Pedro Cuatrecasas’s death, the Spanish scientist Ignacio Vicente Sandoval wrote to EL PAÍS to suggest publishing a story about the deceased researcher, given the widespread silence in the national and international media. Sandoval worked with him for five years half a century ago, first at Johns Hopkins and then at Burroughs Wellcome Laboratories, after Cuatrecasas switched to the pharmaceutical industry in 1975.

“Pedro always kept his Spanish side very much alive; he never renounced his nationality,” recalls his colleague, who recently retired at 75 from the Spanish National Research Council. “He distanced himself from the Nobel Prize when he went to work for Wellcome, but Pedro was very aware that he wanted to focus on developing medicines that could truly be useful to humanity,” says Sandoval.

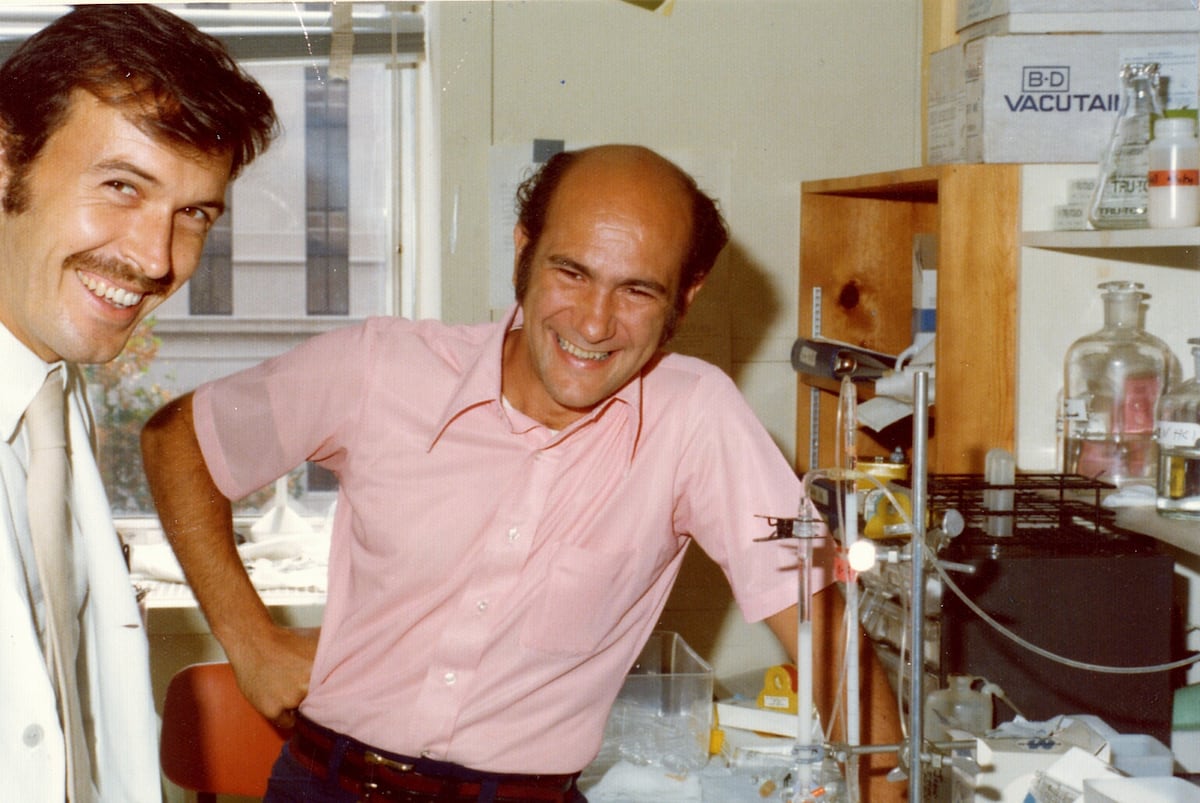

The biochemist Pedro Cuatrecasas with his team at the Burroughs Wellcome laboratories, in the Research Triangle Park (North Carolina), around 1975.

The biochemist Pedro Cuatrecasas with his team at the Burroughs Wellcome laboratories, in the Research Triangle Park (North Carolina), around 1975.

In 2013, Cuatrecasas published a book about his painter brother that included a brief biography of himself. The text highlighted that he had been “involved in the discovery of more than 40 new drugs,” such as the antidepressant bupropion, the antiepileptic gabapentin, the anti-lice treatment RID, and zidovudine, the first antiretroviral drug used against the AIDS virus. In addition to being director of Burroughs Wellcome Laboratories between 1975 and 1985, he was vice president of R&D at Glaxo between 1986 and 1989 and president of Parke-Davis (later acquired by Pfizer) between 1989 and 1997. He was “a giant of pharmacology,” according to the obituary published by the National Institutes of Health.

Sandoval emphasizes the key to Cuatrecasas’s success: he surrounded himself with the best and gave them the freedom to follow their curiosity. The Madrid-born biochemist warned of the end of an era in 2006 in an article titled Drug Discovery in Jeopardy. Cuatrecasas, at 70, criticized the “mega-mergers” of pharmaceutical companies, the voracity of investment banks, the obsession for blockbuster drugs, and the shift of control of research from scientists to marketers. The executives of most of these companies, he said, didn’t understand the complexities of science, its methods or its objectives, and they ran their organizations in ways that stifled creativity and innovation. Before 1980, he believed, things were different. Companies were smaller and not yet controlled by CEOs from business schools. Previously, Cuatrecasas said, employees felt they were contributing to improving the health of humanity.

Curiosity led the Madrid native to discover, around 1969, that the hormone insulin exerts its effect by reversibly binding to the surface of cells, a finding that “arguably launched the modern field of endocrinology,” according to the National Institutes of Health obituary. Sandoval argues that “giving him the Nobel Prize would have been richly deserved, both for affinity chromatography and for the insulin receptor.”

At just 33 years old, his prestige was colossal. Biochemist Vann Bennett, a professor emeritus at Duke University, recalls that he went to work at Cuatrecasas’s “vibrant laboratory” in 1971 because it was recommended to him by the geneticist Daniel Nathans, who would also win the Nobel Prize in Medicine seven years later.

Pedro Cuatrecasas, at a family event in 2015.Colección familiar

Pedro Cuatrecasas, at a family event in 2015.Colección familiar

Endocrinologist Alan Saltiel, a disciple of Cuatrecasas, emphasizes that the latter successively led, for almost a quarter of a century, the research of three of the world’s leading pharmaceutical companies, which led to the development of 40 new drugs, including the cholesterol-lowering drug atorvastatin, which generated some $130 billion until its patent expired.

“It’s impossible to overstate the impact he had on these three companies, not only by establishing the teams that achieved these discoveries, but, even more importantly, by creating a culture of science-based discovery, in which biologists, chemists, clinicians, regulatory experts, and other colleagues could freely explore their intuitions,” applauds Saltiel, director of the Institute for Diabetes and Metabolic Health at the University of California, San Diego. “I think his track record of success proved him right. Unfortunately, this type of culture is rare in the industry today.”

In the digital newspaper archive of the National Library of Spain, there are barely half a dozen mentions of Pedro Cuatrecasas in the Spanish press over the last six decades. EL PAÍS interviewed him in 1987, almost two decades after he revolutionized biomedicine, but he remained unknown even among his colleagues, who used his technique without knowing who had invented it. “Perhaps not everyone knows that I was working to develop the affinity chromatograph,” he declared in Spanish with a strong American accent. “Now it’s no longer necessary to mention me, because everyone knows what it means, but I don’t mind; it gives me great satisfaction. It means that it’s such a recognized and assimilated technique that it’s already part of our working tools.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition