High school science misses a lot of the science researchers actually work with. For example, you learn that there are three states of matter—solid, liquid, and gas—but in advanced physics, things get a bit more complicated. From this complexity, physicists have derived a weird new state of matter: a hybrid between solid and liquid.

Introducing “corralled supercooled liquid.” Like a solid, it contains atoms that stay stationary under special conditions. Like a liquid, most of its atoms are constantly in motion. Remarkably, both of these things can be present at the same time. According to the researchers, who describe the hybrid in a recent ACS Nano paper, this could allow engineers to harness its unique properties for any technology using metals, such as that of the aviation, construction, or electronics industries.

“Our achievement may herald a new form of matter combining characteristics of solids and liquids in the same material,” Andrei Khlobystov, a nanomaterials researcher at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom, said in a statement.

From liquid to solid

Compared to solids and gases, liquids have been trickier for scientists to study, as the atoms inside constantly jostle around. That’s especially true when a liquid starts to turn into a solid. How and where atoms travel ultimately determines the final shape of the solid, but tracing the paths of these atoms is difficult, the researchers explained.

But these exact processes are also responsible for phenomena like mineralization, ice formation, and the folding of proteins. The researchers hoped to find a way to systematically study this critical moment, according to the paper.

Matter in limbo

For the experiment, the team used a specialized electron microscopy device called SALVE. The setup involved an atomically thin sheet of carbon, or graphene, lying under melted platinum, gold, and palladium. The idea was to study how the metals’ atomic structure would change while melting.

“We used graphene as a sort of hob for this process to heat the particles, and as they melted, their atoms began to move rapidly, as expected,” explained Christopher Leist, study lead author and a material scientist at Ulm University in Germany, in the release. “However, to our surprise, we found that some atoms remained stationary.”

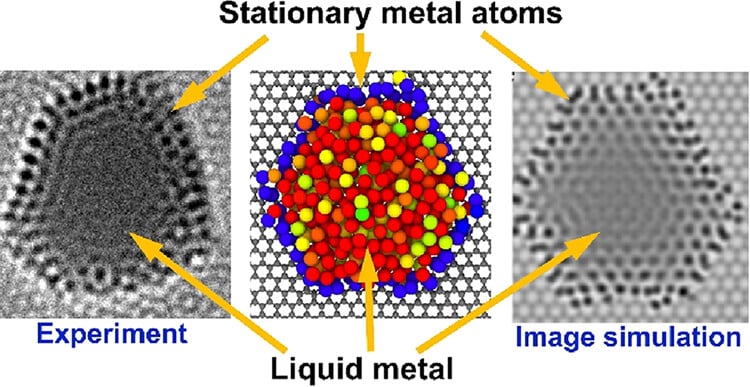

An image of the hybrid structure. Stationary metal atoms are arranged in a blue ring around the liquid metal. © Khlobystov et al., 2025

An image of the hybrid structure. Stationary metal atoms are arranged in a blue ring around the liquid metal. © Khlobystov et al., 2025

The movement somewhat resembled that of electrons in the quantum realm, which exist both as waves and particles, added Ute Kaiser, study co-author and an optics scientist at Ulm University, in the statement. That is, the atoms in the sample behaved partly like the stationary atoms of a solid but also like the continuously active, flowing stream of atoms in a liquid—a “new phase of matter,” Kaiser said.

Crystals be gone?

What’s more, the stationary atoms had a visible impact on the formation of the final solid. A higher number of stationary atoms in the initial structure disrupts the solidification process, resulting in a solid form without any crystals, or an amorphous solid. The solid at this point is highly unstable, the paper noted.

However, fascinatingly, when the stationary atoms are disrupted, that releases enough tension for the metal to transform into its normal crystal form. Similar attempts to coax tiny particles into a certain shape, called corralling, had been achieved for photons and electrons—basically, as tiny as one gets on the nanoscale.

But the new experiment is the first time researchers succeeded in corralling atoms, which are typically much bigger. If scientists can freely control these stationary atoms, that could “pave the way for more efficient use of rare metals in clean technologies, such as energy conversion and storage,” the researchers said.

But if anything, it’s a reminder of the mysteries of nanoscopic processes, especially liquids, they added.