It is an odd feeling to think that while most of us go about our day above ground, a team of researchers are listening for whispers from the universe nearly a mile below the Earth’s surface. Deep in the rock, shielded from sunlight and noise, they are chasing something that refuses to be seen yet shapes everything we know. Dark matter remains one of science’s most stubborn mysteries, and this underground experiment brings humanity one step closer to understanding it.

A journey into the dark

At the heart of this endeavour is LUX ZEPLIN, known as LZ, a detector buried beneath the Sanford Underground Research Facility in South Dakota. The site sits more than 1,600 metres down, an isolation scientists rely on to escape cosmic radiation. Down there, silence becomes a scientific tool. In that hush, researchers hope to catch faint traces of WIMPs – weakly interacting massive particles long considered potential candidates for dark matter.

As experimental physicist Hugh Lippincott has put it, discovering a new particle would be extraordinary, but narrowing the possibilities is equally vital for refining our roadmap of the cosmos. Dark matter is believed to make up the majority of the universe’s mass, yet it still eludes direct detection, shaping galaxies while keeping its identity carefully hidden.

Peering into xenon’s glow

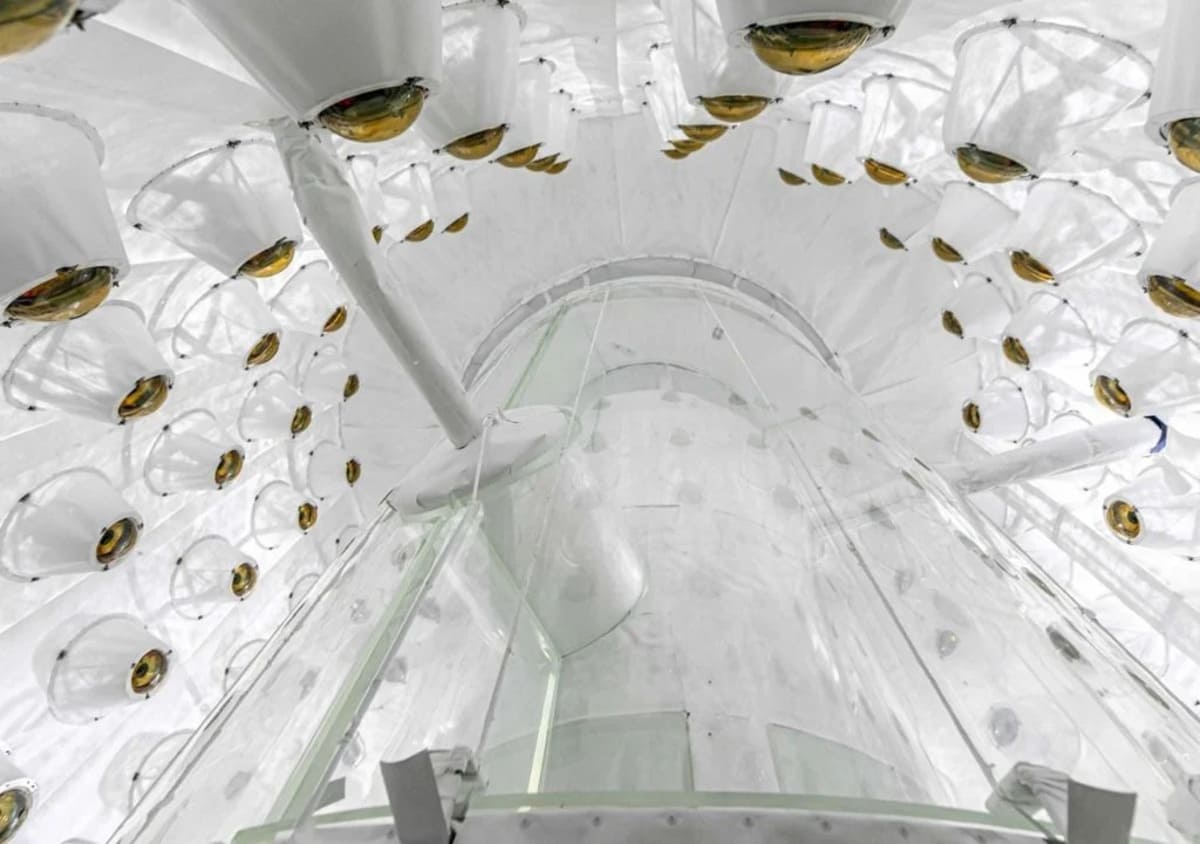

The LZ detector’s core consists of two titanium chambers filled with ten tonnes of ultrapure liquid xenon. When a particle brushes against a xenon atom, even for the briefest instant, it can produce a tiny spark of light – the kind of event the detector is trained to spot. Surrounding this chamber is an outer detector that uses a scintillating liquid enriched with gadolinium, which helps distinguish genuine signals from cosmic background noise.

The latest analysis includes 280 days of collected data, with researchers planning to reach about a thousand days by 2028. In the quiet world of xenon flashes, time is essential. Every additional day allows the experiment to refine its sensitivity and rule out more hypothetical models.

Why build a laboratory beneath a mountain

LZ’s extraordinary sensitivity depends heavily on its environment. By placing the detector deep underground, physicists minimise interference from cosmic rays that constantly bombard the planet’s surface. The structure itself is built from materials chosen specifically for their low levels of natural radioactivity, a detail that would seem almost eccentric anywhere outside of particle physics.

According to the UK’s Science and Technology Facilities Council, background suppression is one of the defining challenges of dark matter research. Each layer of shielding, each carefully calibrated sensor, exists to ensure that any recorded signal is genuine and not an earthly imposter.

Battling the perfect mimics

Among the most troublesome false alarms are neutrons. These neutral subatomic particles are everywhere and, inconveniently, produce signals nearly identical to those expected from WIMPs. Researchers designed the outer detector specifically to track neutrons and weed them out. As physicist Makayla Trask notes, separating the real from the fake is essential if the experiment hopes to make a convincing detection.

Another culprit is radon, a naturally occurring radioactive gas. Its chain of decays can mimic the subtle patterns that scientists associate with dark matter. Fortunately, the team has now learned to identify these sequences and remove them from the dataset, keeping the experiment’s integrity intact.

Science with built in objectivity

To avoid bias, the collaboration uses a technique known as salting, where artificial signals are inserted into the data during collection. Analysts do not know which events are genuine until the review is complete and the dataset is “unsalted”. This approach, used by several major physics collaborations, protects researchers from subconsciously steering the results in a preferred direction.

As study coordinator Scott Haselschwardt remarks, exploring a region of physics no one has charted demands a level head and rigorous objectivity.

Closing in on the invisible

The latest findings narrow the range of what WIMPs could be, trimming away incorrect models and helping steer future experiments. Yet LZ’s value extends beyond dark matter hunting. It is sensitive enough to detect solar neutrinos and rare forms of radioactive decay, broadening the scientific landscape it can illuminate.

With more than 250 scientists across six countries involved, the LZ collaboration is already planning its successor: XLZD, a new generation detector that promises even greater sensitivity. One step deeper into the unknown, it may bring us closer to the moment humanity finally identifies the invisible glue of the universe.

In a cavern a mile below our feet, the search continues – patient, meticulous and quietly hopeful.