Chris Young’s Beyond Earth column explores the intersection of space technology and policy, providing thought-provoking commentary on the latest advancements and regulatory developments in the sector.

In January this year, a Long March-3B rocket lifted off from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center in the southwest of China. Once it had soared to orbit, it deployed the Shijian-25 satellite on a path to achieve a historic milestone for the global space industry.

China’s secrecy, as well as the sensitive military nature of the operation, means Shijian-25’s mission has not been highly publicized. In lieu of official communication from China’s space administration, satellite tracking firms have provided regular updates.

The Shanghai Academy of Spaceflight Technology (SAST) designed Shijian-25 to test on-orbit refueling and mission extension technologies in geostationary orbit (GEO). According to satellite-tracking data, the satellite docked with Shijian-21 over the summer. Last week, the two satellites separated, marking an end to Shijian-25’s first mission.

Global reports indicate that Shijian-25 performed a historic feat, becoming the first satellite to perform an on-orbit refueling operation in GEO. With China increasingly pushing to become the world’s leading space power, it gains a crucial strategic advantage. Beyond the military domain, on-orbit refueling is also earmarked as the technology that will unlock long-duration missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

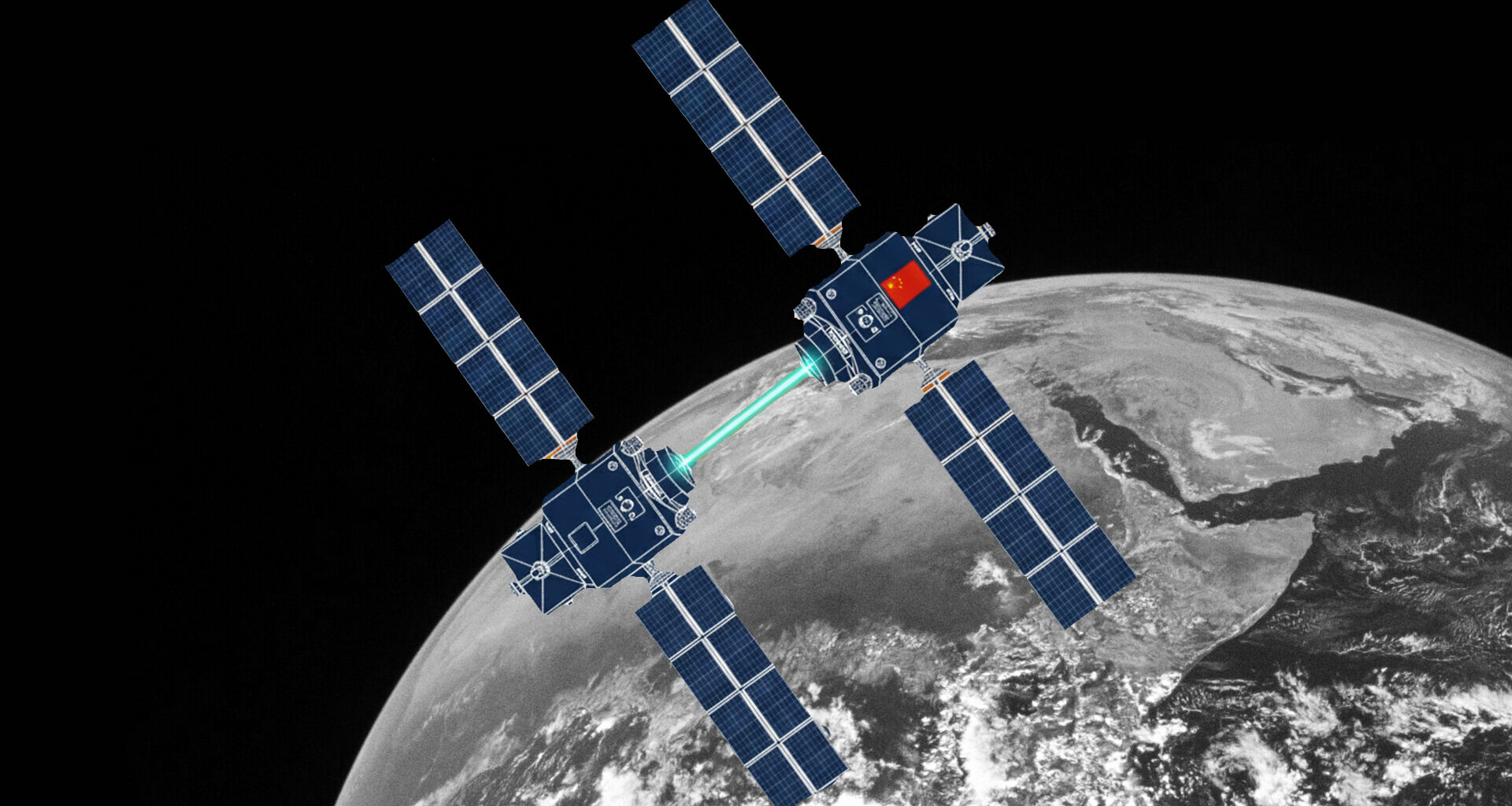

Shijian 21 and Shijian 25’s orbital refueling maneuver

Docking two satellites in orbit is an incredibly complex maneuver. Satellites typically soar through space at an average speed of 17,500 mph (28,000 km/h). To safely dock, they must match position, velocity, attitude (orientation), and angular rate almost perfectly—any difference of just a few centimeters per second or a fraction of a degree can cause a collision that destroys both spacecraft.

While China has remained characteristically secretive about its Shijian-25 mission, the satellite appears to have docked with another satellite, Shijian-21, to perform a historic on-orbit refueling operation. US-based COMSPOC and Swiss firm S2a, two Space Situational Awareness (SSA) companies, have provided unofficial milestone updates on the operation.

In June this year, COMSPOC observed Shijian-25 and Shijian-21 performing several close approaches in geosynchronous orbit (GEO). Shortly afterwards, in early July, COMSPOC explained in an X post that the two satellites “appeared visually merged in optical sensor data”.

“Given the prolonged RPO [rendezvous and proximity operations] time, SJ-21 and SJ-25 may have docked,” it continued.

China launched Shijian-21 into space in October 2021. The satellite performed its own complex orbital operation the following year. It docked with a defunct satellite, Beidou-2 G2, and towed it to a “graveyard orbit” above GEO. This operation left it without fuel, making it a prime target for Shijian-25’s refuel test.

Last week, an S2a update showed that Shijian-25 and Shijian-21 had successfully separated. China’s space administration has provided no official confirmation. However, Shijian-25 has performed a world-first on-orbit refueling test. SpaceNews described it as a “pioneering” test. Breaking Defense noted it was the “first-ever on-orbit refueling test”, while NewsWeek said China has seemingly pulled off “a satellite feat that NASA has never achieved.”

Why on-orbit refueling is key to Space Race 2.0

So why is this so important? The US and China are currently locked in a race for space dominance. The ongoing militarization of space means that satellite operators will increasingly require more fuel in orbit. More fuel allows military satellites to have longer mission lifespans. It also gives them the capacity to perform evasive manoeuvres, if necessary.

In this context, on-orbit refueling provides a key strategic military advantage. It is also a technological milestone that allows leading space powers to signal their power and superiority. While China hasn’t officially acknowledged its on-orbit refueling test, it knows the world is watching. In fact, Interesting Engineering reported in July that two US surveillance satellites, USA 270 and USA 271, were positioned on either side of the Shijian satellites.

The US Space Force has emphasized the importance of orbital refueling as part of its overall military operations. Speaking at the Space & Missile Defense Symposium in August, Space Force General Stephen Whiting said the US must move beyond its existing “one-and-done” approach to satellite deployment. Instead, it should look to deploy orbital gas stations to maintain its leadership in space.

An artist’s illustration of Starship soaring above Earth. Credit: SpaceX/Flickr

An artist’s illustration of Starship soaring above Earth. Credit: SpaceX/Flickr

Beyond military orbital operations, on-orbit refueling is key to the future of human space exploration. In fact, the technology is necessary for NASA’s Artemis III mission, which aims to land the first humans on the Moon since Apollo 17 in 1972. To land a crew on the lunar surface for Artemis III, SpaceX’s modified Starship lunar lander, the Human Landing System (HLS), will have to refuel in orbit before boosting its way toward the Moon.

Refueling is required, in part, because of Starship’s size, which will serve as a lunar base for the week-long mission. The Apollo lunar module was much smaller and could only accommodate a shorter stay on the Moon.

However, the development of Starship HLS is facing delays due to the complexity and unproven nature of orbital cryogenic refueling. In fact, a NASA safety panel recently warned that Starship could be delayed by years. The US space agency is now considering alternatives, with Blue Origin’s MK1 lunar lander, a potential candidate. This means the capacity to refuel could have a direct bearing on the new space race, as experts in the US are increasingly concerned China will beat NASA back to the Moon.

Will the US catch up?

For now, the US is lagging, though it does have its own orbital refueling tests scheduled for 2026. The US arm of global firm Astroscale aims to perform an orbital refueling mission in the coming months. The company is developing the first spacecraft capable of performing a hydrazine refueling operation in GEO. It will also be the first in-orbit refueling mission to support a Department of Defence (DoD) asset.

If all goes to plan, Astroscale’s 660-lbs (300 Kg) APS-R Refueler spacecraft will fly to GEO and rendezvous with one of two US Space Force Tetra-5 satellites.

An artist’s impression of Astroscale’s APS-R Refueler spacecraft. Credit: Astroscale

An artist’s impression of Astroscale’s APS-R Refueler spacecraft. Credit: Astroscale

Despite setbacks, SpaceX is still aiming to perform an on-orbit refueling test in 2026. In a February X post, Elon Musk said “full and immediate reflight of Starship, along with orbital refilling, probably happens next year,” adding that “this is the fundamental breakthrough needed to make life multiplanetary.”

China’s milestone Shijian-25 will go down in history as the space sector ushers in a new era of long-duration missions—both in Earth’s orbit and beyond. The US Space Force is looking to compete with its Tetra program. Scientists have also warned that on-orbit refueling is necessary for a sustainable, circular economy in space. On-orbit refueling, therefore, addresses problems in Earth’s orbit. It provides a strategic military advantage and, ultimately, will allow humans to explore the Solar System and expand humanity’s footprint into the cosmos.