Hybridization of captive giraffes in North American zoos may impact conservation, given the recent scientific consensus that giraffes are four distinct species, not a single species as previously thought.The study recommends international collaboration in future breeding programs, in which giraffes would be captured from the wild in Africa and moved to North American zoos to essentially start a captive-breeding program of genetically pure individuals.But giraffe conservationists say the study’s recommendations would be detrimental to wild conservation, arguing that capturing giraffes for zoos would deplete wild populations.

See All Key Ideas

In the vast savanna grasslands of sub-Saharan Africa towers the giraffe, draped in mosaics of brown and tan patches. Long regarded as a single species, this iconic African megafauna was recently reclassified by the global wildlife conservation authority IUCN into four distinct species: the northern (Giraffa camelopardalis), reticulated (G. reticulata), Masai (G. tippelskirchi) and southern giraffe (G. giraffa).

The tallest living land animal, giraffes wander the open grasslands of Tanzania, South Africa, Kenya and other African nations, as well as appearing in zoos around the world. But their genetic distinctness is largely limited to the wild, as many giraffes held in zoos are now known to be hybrids. Given the new discovery that giraffes aren’t one species but four, the scientific community remains split on how to proceed with conservation, especially in zoos.

Hybrid giraffes and conservation

A new study argues that excessive hybridization of captive giraffes in North American zoos diminishes their conservation value. The researchers analyzed the genetics of 52 such giraffes and then compared their genes to 63 wild giraffes in Africa. The results found that most giraffes in North America were of mixed ancestry, primarily between northern and reticulated giraffes. Only a few giraffes retained their species’ unmixed genetics.

Alfred L. Roca, professor at the Animal Sciences Laboratory at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and lead author of the study, said decades of interbreeding of giraffes in North American zoos has eroded their value as an insurance population. The study shows that offspring of genetically distant giraffes, or hybrids, suffer reduced fitness due to the breakdown of locally adapted genes.

“We found essentially no unadmixed reticulated giraffes remaining,” he said. Roca’s study argues that repeated hybridization of captive giraffes makes them unsuitable for conservation purposes.

“Preserving species integrity is crucial to future breeding programs of giraffes in human care,” Roca told Mongabay Africa in an email.

The study recommends collaborating with “willing African governments, conservation organizations, and regional wildlife authorities” to source wild giraffes for captivity, while emphasizing that this must be done according to multilateral principles like the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) to ensure equitable conservation outcomes.

In addition to this, the study highlights zoos as vital conservation players, where keepers can efficiently collect semen and carry out embryo transfers. It suggests that hybrid animals could be used as surrogates to carry embryos from different wild populations.

In August 2025, the global conservation authority IUCN officially recognized four distinct species of giraffes. Image courtesy of Giraffe Conservation Foundation.

In August 2025, the global conservation authority IUCN officially recognized four distinct species of giraffes. Image courtesy of Giraffe Conservation Foundation.

Giraffes in the wild

When assumed to be a single species, giraffes were classified as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. Between 1985 and 2015, the overall population of wild giraffes declined by 36-40% to an estimated 97,500, according to the IUCN. But the population is starting to recover.

More than 140,000 giraffes now wander Africa, according to latest data compiled by Namibia-based nonprofit Giraffe Conservation Foundation. The data reveal growth in three of the four distinct giraffe species — southern, northern and reticulated — whereas the Masai giraffe has remained stable since 2020.

While Roca’s study suggests capturing genetically pure giraffes from the wild for conservation in zoos, some experts believe this would be detrimental to conservation goals.

Stephanie Fennessy, the GCF executive director, who has studied giraffes for more than 20 years, said that even though zoos play an important role in giraffe conservation, we don’t need to rely on international breeding programs to save the giraffe just yet.

“All four giraffe species should be, and still can be, saved in Africa, by African people who share their living space with giraffes,” she said.

Fennessy said translocations to historical habitats in Africa are powerful conservation interventions, and that wild captures for captive breeding are completely against conservation goals.

According to her, detailed habitat assessments, security and transportation, alongside a clear understanding as to which species or subspecies of giraffes should be moved to which particular area to prevent further hybridization, is crucial for future translocations in Africa.

Fennessy described a project she carried out in collaboration with the Kenya Wildlife Service. That country is home to the northern, reticulated and Masai giraffes, which have historically overlapping territories. For the project, the researchers led by Fennessy collected more than 330 DNA samples of all three species and found no hybridization, despite the animals historically sharing overlapping habitats.

“Giraffes hybridize in captivity; they do not interbreed in the wild,” she said, further emphasizing that wild capture may not be the solution to hybridization of giraffes elsewhere.

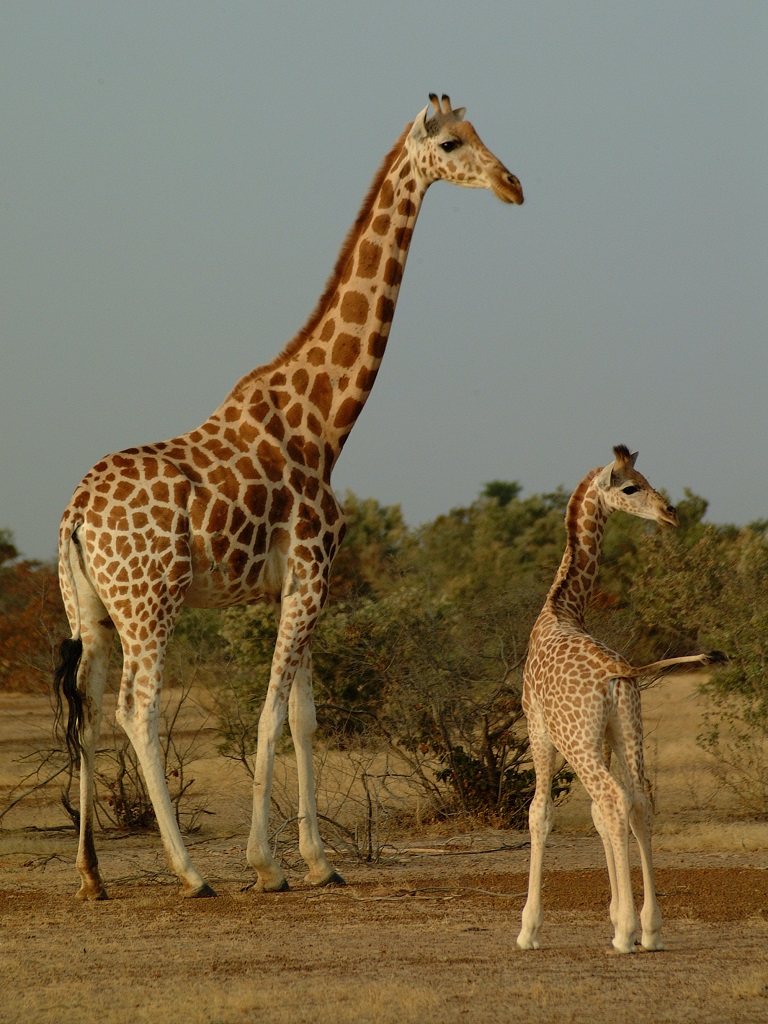

A Northern giraffe with its calf in Niger. Image by Giraffe Conservation Foundation.

A Northern giraffe with its calf in Niger. Image by Giraffe Conservation Foundation.

Will relocation do more harm?

Fred Bercovitch, a comparative wildlife biologist and conservation scientist at the Anne Innis Dagg Foundation in Ontario, Canada, said the study’s proposition to relocate giraffes from African nations to North American zoos is completely at odds with conservation goals, calling it “unethical and immoral.”

Bercovitch, who has studied giraffes for more than two decades, said taking giraffes from the wild depletes the population size of threatened species in their natural habitats in order to strive for the goal of “genetic purity” in captive populations.

“All of the giraffes in North American zoos are threatened with extinction,” he said, adding that genetic distinctness should not be the top priority if saving giraffes is the ultimate goal.

Previous studies echo this argument, suggesting that reticulated giraffes evolved as a consequence of interbreeding between Masai and Nubian giraffes, a subspecies of northern giraffes.

Bercovitch said the taxonomic revision of giraffes into four species and the conservation of giraffes in North American zoos don’t seem to correlate, emphasizing that conservation of giraffes should take place in Africa, in their natural habitats.

He gave the example of Masai giraffes, split into two subspecies separated by the Great Rift Valley in East Africa. “If so, then shouldn’t the Masai giraffe in captivity be divided based on whether they are from the West or East Rift Valley in order to maintain genetic purity?” Bercovitch said, adding that even if one-third of giraffes in North American zoos are hybrids, it shouldn’t be a problem for zoos and giraffe conservation.

A female Masai giraffe in Africa. Image by Giraffe Conservation Foundation and Billy Dodson.

A female Masai giraffe in Africa. Image by Giraffe Conservation Foundation and Billy Dodson.

“The only populations of giraffes that are not threatened with extinction live in Southern Africa, and none of them are found in zoos,” he said, emphasizing that the zoo population in North America rather acts as “animal ambassadors” to educate the public about the plight of their cousins in Africa.

Bercovitch also said the sample size of the zoo study was too small in comparison with the total population of captive giraffes in North America, and as such, the recommendations of the study fail to address conservation concerns, he said.

In October 2025, the U.S.-based Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) published the Giraffe Care Manual, setting forth guidelines on nutrition, habitat, veterinary care and reproduction. But the manual doesn’t mention any differentiated treatment for each species.

“All giraffes found in North American zoos should get the same care,” Bercovitch said.

Mongabay Africa reached out for comment to several of the North American zoos and institutions that provided DNA samples for the study, but none had responded by the time this article was published.

A reticulated giraffe stands tall in Kenya’s Samburu National Reserve. Image by Giraffe Conservation Foundation.

A reticulated giraffe stands tall in Kenya’s Samburu National Reserve. Image by Giraffe Conservation Foundation.

Banner image: A Southern giraffe in Africa. Image by Giraffe Conservation Foundation and Billy Dodson.

Citations:

Au, W. C., Morfeld, K. A., Fields, C. J., Ishida, Y., & Roca, A. L. (2025). Genomic assessment of giraffes in North American collections highlights conservation challenges. Journal of Heredity. doi:10.1093/jhered/esaf089

Koepfli, K-P.. (2024). Evolution: Genomes reveal the reticulated history of giraffes. Current Biology, 34(11), R533-R536. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2024.04.045