What do Ineos Grenadiers, Soudal-QuickStep, Alpecin-Deceuninck’s Fabio Van den Bossche and US para-cyclists have in common? In 2025, they all utilised the most recent addition to the Flanders Cobblestone Paradise Hotel, located close to the route of the Tour of Flanders, namely the normobaric chamber. It can seat up to 20 riders, purports to accelerate recovery, and it’s all down to the joint efforts of oxygen and hydrogen.

Here, we investigate the rationale behind the claims, how amateur riders might benefit, plus inadvertently we stumble into a discovery that could cause WADA a big headache…

Perfect preparation?

Cyclist

Cyclist

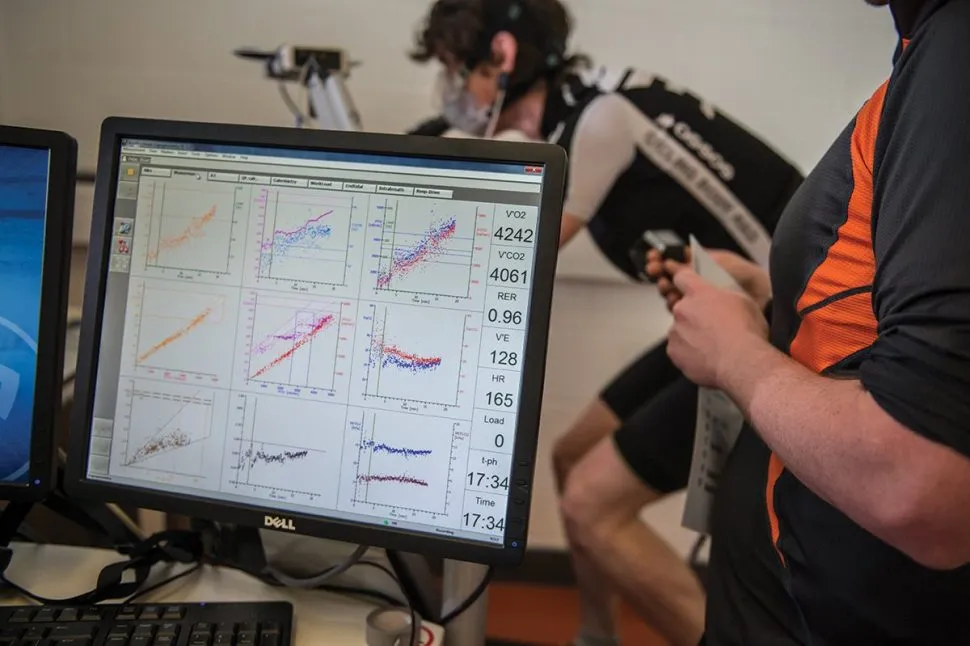

‘During the season, teams have used [the normobaric chamber] to recuperate between classics and in preparation for the Giro d’Italia, while the US para-cyclists have used the facility, too,’ explains Jon Wiggins (no relation), former sports scientist at AC Milan and now, among myriad roles, performance manager at the facility. ‘Van den Bossche also used it ahead of October’s [UCI] Track World Championships in Santiago [where he won the madison].’

Accelerated recovery is the cyclist’s dream, especially the professional whose exploits include Grand Tours – three weeks of relentless daily exertion that drains body and mind. Wiggins’ chamber isn’t mobile (though that could be a glimpse into the future, with mobile recovery chambers sandwiched between the team bus and gear truck en route to the team hotel); instead, compression socks, cherry juice, high protein and carbohydrate refuelling, and even recovery boots are the norm.

But as Wiggins highlighted, this cutting-edge facility comes into its own during the Belgian spring Classics season where a rouleur’s week could feature Gent-Wevelgem on the Sunday, Dwars door Vlaanderen on the Wednesday and the Tour of Flanders the following Sunday. Arguably, he who repairs fastest is best placed to excel.

That’s the aim anyway. But how? What are the mechanisms at play that have attracted the world’s top teams?

‘Key to all the benefits [we’ll come to the specifics shortly] is achieving “hyperoxia”,’ says Wiggins. This, as you might suspect, is exposing the athlete to oxygen levels that are higher than normal air (which is around 21%). The opposite is hypoxia, as per altitude training, which is lower than 21%.

‘Oxygen content is up to 40%,’ says Wiggins. ‘There’s also a pressurised element to proceedings. The earth’s atmosphere is around 1 atmospheric pressure. In the chamber we’re looking at around 1.5 up to 2 atmospheric pressures. We know from Boyle’s and Henry’s Laws that it’s important to understand this and its impact on oxidation at the muscular level.’

The science is vital and hey, we’re modern cyclists – we chow down on data and evidence for breakfast (alongside slow-releasing porridge and power-boosting coffee, of course). So, a swift albeit technical explainer…

In terms of hyperoxia, Henry’s Law explains the main physiological effect: that breathing oxygen-enriched air increases the partial pressure of oxygen, allowing more oxygen to dissolve directly into blood plasma. This is despite haemoglobin being almost fully saturated (and why any performance benefit is potentially short-lived).

Boyle’s Law, meanwhile, is mainly relevant in pressurised settings, where increased pressure reduces gas volume and raises oxygen pressure in the lungs, further increasing dissolved oxygen. But, again, it doesn’t lead to lasting oxygen storage. Together, these laws explain why hyperoxia can provide brief, acute advantages.

These advantages include reduced inflammation, acceleration of recovery and even cranking up wound healing. Cristiano Ronaldo, arguably the most famous proponent of oxygen therapy, was seeking all three when he invested in a hyperbaric oxygen machine for his Cheshire home during his second spell at Manchester United. Chris Froome also extolled the benefits when recovering from his horror crash of 2019. Both sought out an oxygen boost. But, says Wiggins, they were missing the secret ingredient that he feels separates Paradise from the norm.

Hydrogen, the unheralded atom

Cyclist

Cyclist

‘In our chamber, we have the complementary effect of hydrogen gas,’ says Wiggins. The chamber’s hydrogen content is 1,000 times that of the atmosphere. ‘Hydrogen gas is intriguing as it works as an antioxidant and an anti-inflammatory. It has many benefits but only under a pressured environment. Remove it from that environment and it’ll immediately lose its properties to the atmosphere.’

Together, the oxygen and hydrogen chamber deliver myriad positives conducive to recovery, says Wiggins. As a snapshot, heart rate drops, heart rate variability rises and circulation increases, despite that heart rate drop. From the data, this clears out the metabolites that impair recovery. It also emboldens your most effective recovery tool.

‘Riders who use the chamber enjoy a much better sleep, especially during the deep sleep stage,’ says Wiggins. ‘This is particularly important as it’s during deep sleep that your mind and body recovers.’ The data also showed markers of immunity shifting up a gear, too.

‘We’ve also had marathon runners in here, recuperating after a race,’ Wiggins says. ‘Anyone who’s run a marathon knows how sore your muscles are afterwards, but they reported lower levels of muscle soreness than normal, plus lower levels of physical and mental fatigue.’

The results have also proved positive when doubling up on recovery methods, with riders hitting the chamber for active recovery sessions while easy-pedalling on Zwift, plus sedentary efforts with their legs in a pair of Reboots – compression apparel that inflates to apply pressure in search of removing waste products.

And a spot of high oxygen and hydrogen inhalation has seen positive results when pre-loading. That means prepping pre-exercise within the chamber before unleashing a stronger effort. Basically, a warm-up that delivers super-sized benefits.

Gut health’s another area where there’s compelling evidence the chamber helps. And finally, your mind.

‘In our tests, we can see via analysis of the frontal cortex of the brain that the increased oxygenation is delivering positive – and for us as scientists – data-driven adaptations.’ Wiggins caveats that there’s currently minimal evidence that these benefits last, albeit that could simply be down to insufficiently long studies.

On the face of it, the chamber is the performance panacea. Then again, no tool or strategy guarantees success – Ineos Grenadiers’ 2025 Belgian Classic and semi-Classic win rate remained at zero – but it does offer a glimpse into the lengths the professionals go to in search of success. That said, recreational riders often visit, albeit it’s clearly impractical unless you live in the area or you’re tackling an amateur event like the Tour of Flanders Sportive. (Even with my frugal hat on, the pricing seems respectable: it’s €30 for a two-hour session or €180 for one night’s accommodation including a session.)

There is evidence that the more practical hydrogen-rich water might reduce exercise-related oxidative stress and support recovery through selective antioxidant effects, but it doesn’t directly enhance performance and evidence remains mixed.

Hydrogen machines are by no means new either – China used them in a therapeutic setting to treat Covid patients. They’re about the size of a domestic coffee machine and, for the performance-seeking rider, might appeal if budget allows.

WADA’s potential nightmare

Wiggins is a credible and acclaimed sport scientist. The evidence certainly appears to support the sell, albeit peer-reviewed studies into the facility would be the next step. But it got me thinking, what if there was a free method of potentially enjoying these gas-based recovery benefits, a way that was more democratic and would create hyperoxia without the need for any tool? I dug into the studies, but hit a brick wall.

I then tapped up a former coach at WorldTour level who is like the Yoda of cycling science to check if he was aware of any methods. He said no, ‘but I have something of even greater interest’. Interest piqued.

‘I can’t disclose too much, which is why I wish to remain unnamed, but here’s a heads-up. I’ve found a way to increase haematocrit levels, which is going to cause big problems for WADA [World Anti-Doping Agency]. I’ve already been in contact with Anti-Doping Denmark about it. It’s legal and is akin to undertaking an altitude camp at home.’

Haematocrit is the percentage of your blood that’s made up of red blood cells. As red blood cells carry oxygen to your working muscles, the higher the better (within reason), certainly for an endurance athlete. An adult man’s is around 41% to 45%; a woman 36% to 41%. Historically, the alarms would go off at WADA if haematocrit levels tipped over 50% as that was often a sign of doping. Back to our insider and his potentially game-changing revelation…

‘Eukaryotic cells first appeared about 1.6 billion years ago when there was far less oxygen in the air,’ he says. Most scientists think it was around 1% of today’s level of roughly 21%. So, we’re looking at around 0.2% oxygen. ‘Fast-forward to the present day and the majority of our cells have held onto this low oxygen environment.’

In other words, our cells function at an oxygen level that harks back to times gone by. For arterial blood you’re looking at 13% to 14% oxygen; most body tissue is 1% to 7%; while bone marrow, cartilage and parts of the gut and skin are around 1%.

What our former WorldTour coach has discovered is that by agitating what he calls ‘the latent potential of these ancient cells’, you stimulate the production of erythropoietin (EPO). This is down to oxygen-sensing proteins that our man’s become obsessed by. ‘They are hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF-1, HIF-2 and HIF-3). When oxygen is low, HIFs switch on the EPO gene, increasing red blood cells to improve oxygen delivery.’

This discovery proved central to the 2019 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine going to William Kaelin, Sir Peter Ratcliffe and Gregg Semenza. They identified the molecular mechanisms and machinery that regulate gene activity depending on oxygen levels.

From Nobel prize to performance

Cyclist

Cyclist

‘That’s when I dusted off my old textbooks,’ he says. What he discovered has seen him knocking on WADA’s door: that by following a regimented protocol of breathwork, you can stimulate EPO to levels that match that achieved at altitude.

‘We’ve undertaken studies, we’ve ticked off blood tests, we have the data, and we’ve shown individuals can boost their haematocrit levels from 42% to 48% within three weeks thanks to daily 15- to 20-minute breathing work.’ That 15- to 20-minute period is the time it takes to activate HIF-1 into cranking up EPO production.

This physiological adaptation, he adds, results in a performance boost across the power profile, from one minute to 20 minutes. Key, he says, is that the breathwork is individualised – he’s clear that he is working on an app that is due to go live soon – plus you measure oxygen-saturation levels via your finger.

‘Basically, you’d treat it like a traditional altitude camp, but without having to leave your home. So, you’d ensure your iron levels are stable in the four weeks before and don’t lower bodyweight, either, as you need extra energy at “altitude”. Then, you might ride pretty hard – like 40/20s [40sec hard, 20sec recovery] – fuelling properly. Finish, sit down and listen to the app, which will guide you through the breathing protocol – via AI, what else? You’re given a personalised breath-holding programme based on your current level. It’ll register your oxygen-saturation levels and you’ll be told to hold your breath longer or back off. Simple.’

Obviously, I can’t verify the claims but I have seen the confidential background data, the patent is in place, and the source and evidence is credible. In a recent feature, breathing expert Patrick McKeown told us the field of breathing – or of not breathing, in the case of hypoxia – will accelerate in the next five years. He could well be right. Keep an eye out for developments in 2026.

All in all, facilities such as the normobaric chamber at Flanders Cobblestone Paradise represent the sharp end of marginal gains. The science behind oxygen- and hydrogen-assisted recovery is plausible, intriguing and supported by data – even if the benefits appear acute rather than transformative.

But the real significance of this story may lie not in a chamber hidden away in Belgium, but in the growing understanding of how the body senses and responds to oxygen itself.

If performance gains comparable to altitude adaptation can be triggered through something as simple, legal and democratic as breathwork, then cycling – and anti-doping – could be heading for a far bigger reckoning than any sealed room filled with enriched air.