Cyclone Senyar brought over 1,000 mm of rainfall to North Sumatra in late November, triggering massive floods and landslides across the region. Among the hardest-hit areas was the West Block of the Batang Toru ecosystem, home to more than half of the fewer than 800 remaining Tapanuli orangutans. Their absence in the weeks that followed has left conservationists gravely concerned.

Recognized as a separate species only in 2017, the Tapanuli orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis) is confined to just three isolated populations on the island of Sumatra. Long threatened by habitat fragmentation from logging, mining, and palm oil expansion, these apes are now grappling with a new and more immediate threat: climate-driven extreme weather events. The intensity of Cyclone Senyar, combined with the apes’ extremely low reproductive rate, has led experts to describe the event as an “extinction-level disturbance.”

Habitat Collapse in Batang Toru

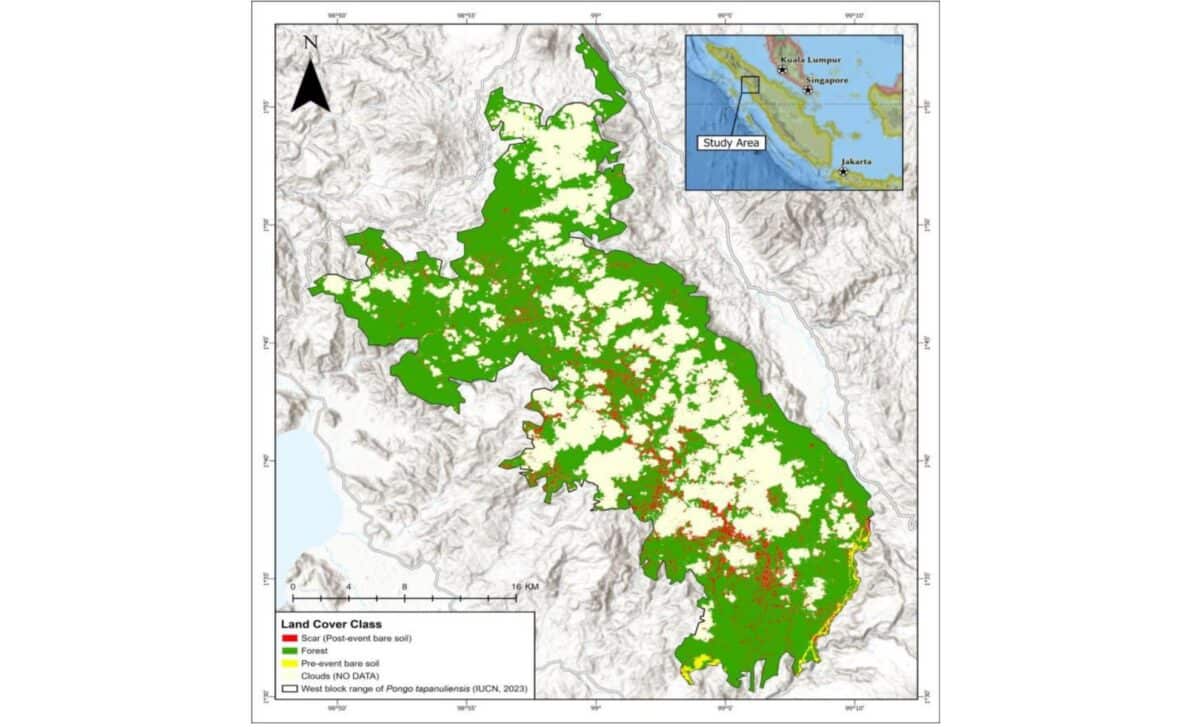

The forest damage caused by the late-November cyclone was unprecedented. Based on satellite imagery analysis carried out by a team led by biological anthropologist Prof. Erik Meijaard, at least 3,964 hectares of forest were completely destroyed by landslides and flooding. A further 2,487 hectares may have been affected but remain unconfirmed due to cloud cover.

“These areas show as bare soil on satellite imagery where two weeks ago it was primary forest,” Meijaard explained to BBC News. “Complete destruction. Many patches of several hectares completely denuded. It must have been hellish in the forest at the time.” The same study estimates that 33 to 54 orangutans likely died or were severely impacted, a demographic loss considered catastrophic for a species whose populations are already isolated and extremely vulnerable.

On the ground, humanitarian workers reported finding at least one carcass believed to be a Tapanuli orangutan, partially buried in mud and logs near the village of Pulo Pakkat. According to Deckey Chandra, who has experience working on Tapanuli conservation, “they used to come to this place to eat fruits. But now it seems to have become their graveyard.”

A Species Too Slow to Recover

Unlike other primates, orangutans reproduce slowly, females only give birth once every six to nine years. Losing even a small number of individuals in a single event can undo decades of conservation efforts. According to the preprint led by Meijaard’s team, an annual mortality rate exceeding just 1% is enough to send the species into irreversible decline. In this case, the estimate ranges from 6.2 to 10.5% mortality in just a matter of days.

Meijaard told The Guardian that the path to extinction has now become “a lot steeper.” The affected apes were mostly concentrated in the West Block, which held the largest known population. With parts of the forest now flattened and food sources destroyed, surviving orangutans are likely facing physiological stress, limited resources, and potentially dangerous displacement into degraded or human-modified habitats.

In a review of satellite data, remote sensing expert David Gaveau described his reaction: “I have never seen anything like this before during my 20 years of monitoring deforestation in Indonesia with satellites.” The images show scars running more than a kilometer across the steep forest terrain, with some gashes nearly 100 meters wide.

Human Impact and International Response

While local weather conditions were influenced by a La Niña phase and a negative Indian Ocean Dipole, scientists say that human-caused climate change likely played a major role in amplifying the intensity of rainfall. According to a rapid attribution study cited in the preprint, climate change increased the likelihood and intensity of this type of extreme event by 9% to 50%.

In response, the Indonesian Ministry of Environment temporarily suspended all private-sector activity in the Batang Toru area. Conservationists have welcomed this move, calling for an immediate moratorium on land development and expansion of protected areas. “This fragile and sensitive habitat in West Block must be fully protected by halting all habitat-damaging development,” urged Panut Hadisiswoyo, founder of the Orangutan Information Centre. But the damage has already been done. With parts of the forest rendered uninhabitable and its scattered orangutan populations further destabilized, the race to prevent the first great ape extinction in modern history has entered a new, more urgent phase.